Words & pictures: Eddie Procter via Landscapism.

This is the story of a day spent exploring seven crossings of the River Severn below Gloucester as it morphs from a meandering river into a mighty tidal estuary flowing through the Bristol Channel and on into the impossible beyond of the Atlantic Ocean: three ferry passages, a railway bridge, a railway tunnel and two road bridges. A backwater estuarine landscape dissected over the centuries by communication routes ferrying goods and people from the coalfields and iron foundries of South Wales, the Irish Sea port of Fishguard and the timber lands of the Forest of Dean to Bristol, London and beyond. The road bridges and railway tunnel remain, transporting their sleek machines between England and Wales, but the railway bridge is lost beneath the water and the ferries are long gone, given a last hurrah, curiously, by Bob Dylan in 1966.

First up, an attempt to view the eastern entrance to the Severn Railway Tunnel. Constructed between 1873 and 1886, this subterranean ‘crossing’ is over 4 miles and long and, until the opening of the Channel Tunnel, was the longest in Britain’s railway system. On the map this looks an easy stroll from the road, but this is a working mainline and I predicted that access could be tricky; and so it proved to be. Although a footpath circumnavigated the entrance, its location in a deep cutting bounded by overgrown embankments and ditches prevented any possibility of viewing from the right of way. High steel fencing completed the sense of prosaic impregnability. If Railtrack were responsible for designing the ramparts and palisades of Iron Age hill-forts, this is how they would look.

So, a detour is required across fields, marked by the humps and bumps of medieval ridge and furrow, to clear the range of the security fencing, negotiate a more conventional wire fence and plunge into bush and brier to ascend the embankment. Eventually a way is found through the nettles and thorns and a view of the cutting is won. Sadly, a service road in full sight of a nearby maintenance depot would need to be crossed to obtain a full view of the turreted tunnel entrance. A little disappointed, I retrace my tracks and noticed that the gate to the depot is now open. Two fluorescent coated workmen are preoccupied with checking machinery and do not notice my brief trespass to the top of steps down to the tunnel entrance; and so I get the close-up photo I had been seeking.

As I trudge back to the car I muse on whether it should need to feel this subversive – should require a mild law-breaking adventure – in order to see a wonder of Victorian engineering. I’m sure a National Trust style visitor centre would diminish the experience in a different way, but there must be a happy medium.

Half a mile away at New Passage and the ghosts of an older method of transportation, the ferry, haunt the shadows of the Second Severn Crossing Bridge, the gleaming conveyor of the M4 motorway across the estuary. Until the railway tunnel opened (almost directly beneath) the New Passage Ferry was the most direct connecting route from South Wales to England if a long circuitous route north via the bridge up-river at Gloucester was to be avoided. An example of the impossibly localised companies that sprang up during the railway mania of the mid-nineteenth century, the Bristol & South Wales Union Railway opened a line to a terminal pier here for passengers to board the ferry across to Portskewett. The ferry route’s lifetime was though short-lived and it only operated between 1863 and 1886. The pier is long gone but its stone bulwark forms part of the flood defence topped by a foot and cycle path which gives suitably breath-taking views of both the Second Severn Crossing bridge and the original Severn Bridge just three miles further upstream. Opened in 1996 to provide a more direct route for the increased traffic volumes of the M4, the new bridge seems to display a haughtiness towards its precursor as it curves away southwards. Seen from the heights of the Forest of Dean or the Cotswold scarp the two structures seem like diverging monolithic siblings, two contrasting characters forever linked by their utility.

The Second Severn Crossing

The Second Severn Crossing

The Severn Bridge

The Severn Bridge

Next stop is a relic of a more ancient crossing, the remains of the jetty serving the Old Passage Ferry at Aust. This route was used from at least the early medieval period (and probably stretching further back into antiquity, as a route to the Roman settlements at Caerleon and Caerwent) until 1966, when the Severn Bridge was opened. It crossed the estuary at its narrowest point to a protruding spit of land on the western shore at Beachley, formed from silt deposited by the converging River Wye. The jetty and ticket office, replete with rusting turnstile, are slowly falling apart; abandoned to their decrepitude but easily accessible, no barbed wire or signs of danger or prosecution to bar the curious.

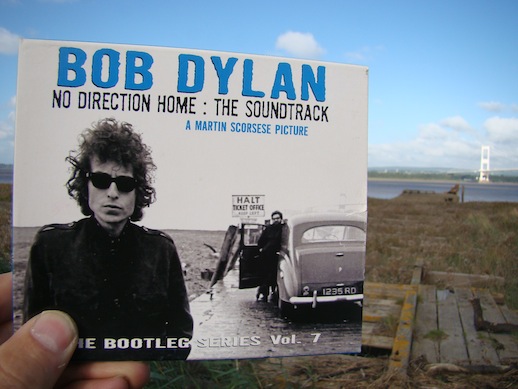

The jetty also provides an interesting footnote to Bob Dylan’s tumultuous 1966 European tour, during which he shape-shifted from acoustic to electric folk to cries of ‘Judas’ from the, no doubt bearded, puritans. An iconic photograph from the tour by Barry Feinstein sees Dylan (every inch the new model rock and roller: Chelsea boots, drain-pipe jeans, shades and unruly bush of hair) standing on the approach to the jetty waiting for the ferry, doomed to close later that year; the modernity of the new Severn Bridge just visible looming through the greyness in the background.

So with Like A Rolling Stone in my head, but displaying a much lower quotient of effortless cool, I trod the rotting boards of the jetty through a jungle of eight foot high spartina (rice grass, introduced in the early twentieth century to help stabilise the shoreline) to emerge on the mud-flats; here the immensity of the estuary spread before me, eyes lifted to the gleaming white carriageway and massive steel towers of the suspension bridge, geographically close but temporarily centuries apart. From this point on, the boards have gone and just the timber footings and cross beams remain, but it remains a wondrous spot for a photo-opportunity.

With the weather due to close in, now was the time to take a walk on the Severn Bridge. Unlike the interloper to the south, the original bridge has walkways and cycle paths spanning its length. Although time was against walking the two miles to the western end of the bridge and back I stepped out to the middle, feeling the life of this inert structure through the wind whipping in from the north – seemingly directly from the uplands of Plynlimon, and the vibrations beneath my feet as juggernaut’s shuddered by. Meanwhile my smart phone experienced stage fright as the camera refused to focus when pointed upwards to the 450 feet high support, as if awe-struck, as I was, by the intensity of the vision in its sights.

The final destination for the day was up-river, around the watery industry of Sharpness. Sharpness is an old-school, but still functioning, dock that has a definite end of the road feel. It was established at the point in the river after which navigation for large ocean-going ships becomes difficult. The opening of the Gloucester to Sharpness Canal in 1827 enabled smaller vessels to transport loads to Gloucester and thence on into the Midlands. Having parked, appropriately, at the end of the road I had hoped to follow the course of the now defunct railway line, a spur of the main Bristol to Birmingham main line, which fed the lost Severn Railway Bridge. It soon became clear that this was another case of map and fact mismatching, the cartographical lines harshly obliterated by the reality on the ground. Instead I headed for Purton, a few country lane winds away and the location of the seventh and final Severn crossing, the Purton Passage Ferry. And here I would come across a melancholy surprise in the rainy gloom, as the grey-browns of the river, mud bank and sky threatened to merge into a single entity.

The earliest recording of a ferry crossing from Purton to its namesake settlement on the west bank is 1282 and it continued t0 be used until 1879 and the coming of the railway bridge. From here the canal runs parallel to, and yards from, the river and I followed the tow-path to lead me to the residual architecture of the bridge.

But first I was to wander through a unique graveyard. To prevent the erosion of the thin strip of land between the powerfully tidal river and the canal, throughout the twentieth century and up to the mid 1960’s barges and small ships were hulked at high tide and left to fill with silt on the foreshore to help prevent erosion. For half a mile the remains of these vessels litter the shoreline, some almost totally submerged in the mud and grass covered; others like the skeletons of long extinct dinosaurs, weathering away the years. Thanks to the work of the Friends of Purton each wreck has been recorded and marked by a discreet plaque with basic details. As with grave stones in a church yard this enables the visitor to potter through the remarkable history of the dead; perhaps most notably the ‘Katherine Ellen’, impounded in 1921 for running guns for the IRA.

A bend in the canal turned and there standing sentinel stood the remains of the bridge. But first the story of the bridge and its shocking demise, as recorded at the site:

“On 25th October 1960 the bridge suffered a tragic accident. Thick fog and a strong tide meant that boats entering Sharpness Dock were having extra difficulty. Tow tanker barges, the Arkendale H and Wastdale H, laden with oil and petrol missed the entrance and were carried upstream towards the bridge. The Wastdale H collided with column 17, her petrol tanks ruptured and the force of the tide pushed Arkendale H on top of her.

The collision caused two bridge spans to collapse rupturing a gas main and electric cable. There was a mighty explosion and the barges burst into flames. Fire spread across the river as oil and petrol spilled into the water. Of the eight crew only three survived having swum to the safety of the shore. It was not economically viable to rebuild the bridge which was later demolished. At low tide it is still possible to see the remains of the tanker barges lying in the river mud.”

All that now survives are the circular engine house, built to power the swing bridge over the canal, and the bridge’s first arch; majestic ruins, as ancient looking as any medieval fortress. An industrial archaeology quest had been fulfilled, providing a fitting end to a day of discovery, traversing temporal and spatial boundaries in search of seven crossings.