Sick On You: The Disastrous Story Of Britain’s Great Lost Punk Band by Andrew Matheson.

Ebury Press, paperback, 352 pages. Out now

Review by Ben Myers.

Most hugely successful rock stars are boring. Once you have got over the initial dream-like oddness of being in their company, the mundane reality kicks in. Ozzy can’t find his glasses – have you seen them? Lemmy has peaked early, been sick and wants to leave. You have a little nap while interviewing the singer from The Killers and when you awake he’s still talking about microphones. Even Motley Crue are clean and serene these days. And have you been on Axl Rose’s Twitter feed? That dude’s so bored he mainly posts pictures of sausages.

Because the biggest rock stars stop trying. Life is smooth and satisfying. Easy. Yes, Lou Reed’s week might have beaten your year and who wouldn’t want an audience with The Ig, but those guys come from a different intellectual and artistic place. They’ve known hard times, never became millionaires overnight. The rest simply aren’t hungry.

And so it follows that the very best rock biographies and biopics are those that tell of starvation and desire, struggle and failure. Ill timing and bad luck. Near misses. Those stories of bitter bridesmaids, self-sabotage and naiveté. Think of Slade’s melancholic, fictionalised tale of shattered dreams in Flame, Ian Hunter’s Diary Of A Rock N’ Roll Star, Anton Newcombe lamping his own band-mates during their big industry showcase in Dig! or how much more enjoyable and human Anvil was next to Metallica’s Some Kind Of Monster. Twenty-Four Hour Party People worked because it was about grandiose ideas rubbing against cold fiscal reality; hedonism versus business. Success, yes – but failure too.

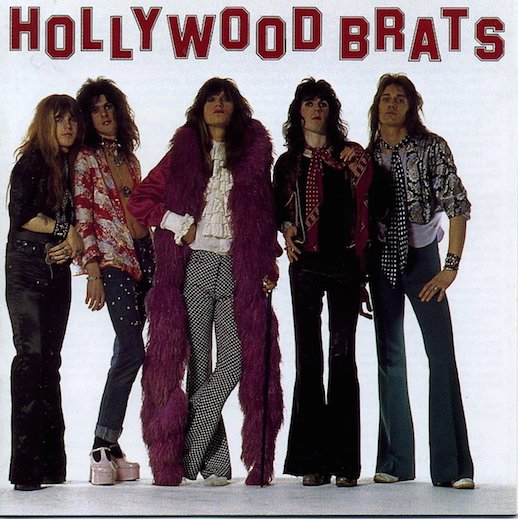

Right from the opening page, Andrew Matheson’s account of his time forming and fronting Hollywood Brats reads like an instant classic and welcome addition to that shrunken sub-genre of music memoirs that are imbued with a sense of arête – excellence in the face of adversity – where so many biographies written by life’s winners offer little other that hubris: excessive pride, self confidence and arrogance. We want dirt, idiocy, humour, tragedy, grit and excess, and Sick On You offers this in abundance, while also serving to remind that the distance between success and failure is but a mere pubic hair apart, and that history still favours the winners. To the victors belong the spoils and all that.

Brit-born Matheson moved to London from Canada in 1971 aged 18, armed with a thousand bucks earned working down a Canadian nickel mine, an idea to form a band and list of rules that they would adhere to (“Great hair, straight hair, is a must…if a member starts going thin on top put an ad in Melody Maker”, “No facial hair [either]…Jerry Garcia is no sane, recently showered girl’s idea of a pin up”).

Working folding clothes in Moss Bros by day, bad luck strikes Matheson early, when in a true rock rites de passage he catches a dose of crabs after a Tyrannosaurus Rex gig, and is advised to “try Dettol”, which he promptly pours over himself in his communal bed-sit bathroom, and nearly burns his young junk to a smoking stump. Not a good look for a singer; not a good look for anyone.

Nevertheless he is still the type of preening peacock you want leading from the front – someone who dismisses Jim Morrison as “a bloated, bearded metaphor” and describes Mick Jones as someone who flaunted convention in the 80s “by going defiantly bald” – yet instantly identifies ‘Get Down And Get With It’ by Slade as one of the greatest songs ever written (no argument here) and holds a torch for The Kinks’ Something Else.

His evocation of a music scene bulging with hirsute blues rock-bores in an austere England still dining on the basics of egg and chips, mugs of Tizer and casual violence is as accurately rendered as any you will read. The depth of poverty and hunger that the young Brats (who originally go by the name The Queen; they change it at the behest of another band, but not before Matheson has punched their toothsome singer Freddie to the floor of the Marquee) must endure makes Withnail & I look like a Roman symposium.

Opportunistically stealing a box from outside a shop at 5am, they lug it home only for a bed of aggressive eels to leap out and make for the door while our humble heroes, clad in blouses and heels, freak out. Rice is their only staple food while tea bags are re-used, then roasted and smoked. At one point while reading One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich, Solzhenitsyn’s harrowing account of life in the Siberian Gulags, a famished, unemployable Matheson genuinely envies the prisoner’s diet of potato peelings broth and sawdust bread. His appetite does not extend to learning the inane lyrics of rock n’ roll standards they’re forced to play for quick cash, however. Of ‘Jailhouse Rock’: “Do you know what Bugsy said to Shifty? Me neither. Turns out to be ‘Nix, nix’. Who’d have guessed?”

Matheson – like all singers – is also ruthlessly, cattily competitive. When he first sees a picture in the NME of the New York Dolls, a band with the same attitude and aesthetic as his own, but already in possession of record contract, he is gutted. He’s near inconsolable though when he reads that their drummer Billy Murcia has died at a party in London: “What is it with these Dolls? I’d lose Roger in a heartbeat for that kind of press.” When he is finally offered a one album/£2000 deal with Polydor he turns it down: “Too chintzy.” And that’s all before a weekend getting wasted at Cliff Richard’s Tudor country pile, the patronage of Keith Moon, fleeting appearance from David Bowie, young acolytes Tony James and Mick Jones and all manner of celebrities; everyone from Francis Bacon to Peter Wyngarde send drinks over to these strange creatures in the corner booth.

Now in his sixties, Matheson has a keen eye for the hopeless absurdity and doomed romance of the rock world, where posture and pose is what really matters. His energised prose and endearing, clownish cast recall those of Julian Cope’s Head On and Repossessed, two of the finest music tomes of our time. An officer who searches Matheson after he is arrested for stealing three bottles of Coca-Cola is “sickened” to find his only possessions are a 2p coin and a tube of lipstick – “Cherry Blaze-Outdoor Girl”.

But The Hollywood Brats do something right: they look amazing, and they help steer music away from fading glam, student prog, earnest folk and a leaden 60s hangover towards something cockier, more provocative and resolutely designed to shake, rattle and roll the sensibilities of an alternative England that is ruled by aggro bikers, quasi-fascistic Teds, bully-boy coppers and everyday citizens who, despite the good groundwork of Dame Ziggy Bowie, are still not massively enamoured by a six-foot something loudmouth with “more front than Jayne Mansfield”. We can recognise it today as something called punk. At one point The Brats are even given a nasty hiding by an ultraviolent gang dressed as Clockwork Orange droogs; it seems things like this really did happen.

And that’s where the power of this story lies: like all the pioneers, The Hollywood Brats suffered nothing but hell at the time, some of it self-induced. They arrived early and left before the real party began. When they do finally sign a deal, it turns out to be not to a record company but a production company (big difference), run by the intimidating Wilf Pine, one of the few Englishmen to make in-roads into the Italian mafia, and bankrolled by two unseen East End brothers called Ronnie and Reggie.

Their shambolic, tottering combination of Stonesy-grit, charity shop glam and bawdy lyrical nihilism (“I’m gonna be sick on you / All down your face, your dress, your legs and your shoes…”) influenced The Clash, Sex Pistols and Malcolm McLaren, who attempts to manage them, and can be heard over the intervening the years in everyone from Cockney Rejects to Hanoi Rocks, Guns N’ Roses, early Manics and dozens of other bands (Towers Of London, anyone?), but unlike the Dolls, they had no-one fighting their corner or curating their catalogue in the intervening years; no provincial fan-club keeping the flame alive. Not even a Morrissey. No member carved out a successful solo career. No film soundtrack slot brought them an unexpected windfall or prompted a comeback. Their one album came out in Norway, where it sold five hundred copies.

Sick On You – and let’s take a fleeting moment to recognise the all-important, history-changing difference between ‘on’ and ‘of’ in this instance – is a brilliantly misanthropic account of this silly business of show. Andrew Matheson emerges from the story exactly the type of brilliant bell-end and self-aggrandising, swell-headed legend that Britain is so good at producing. He has also written one of the great rock reads.

Sick on You is available in the Caught by the River shop, priced at £12