by Chris Yates, from his forthcoming book ‘Out Of The Blue’.

Originally published in yesterday’s Telegraph.

The chug back west in late afternoon became increasingly bumpy as a breeze picked up from the south, and by the time we got back to the cottage there was a proper wind blowing. My fishing companion, Matt, left for home at sunset, and after his car had rolled away down the lane I walked back to the cliff edge to find that, in the hour since we’d come ashore, the sea had grown tremendously. Big white-crested waves were surging into the beach and, from the bottom of the steep path, the noise seemed deafening. A crescent moon, hanging in the south-west, tried to remain calm, but though the sky was still clear there was a treacherous look about it.

I let myself be blown back to the snug cottage, where I made a tasty supper with two of the seven mackerel we’d caught earlier, served with spinach and potatoes, and mint from the garden. As darkness fell, and some heavy weather swooped in, a voice on the radio reminded me that tonight was the twentieth anniversary of the Great Storm of ’87.

The wind howled and the rain hissed all night, yet I slept deeply, only stirring a couple of times as an extra big gust rattled the windows. When I finally woke, at the sensible time of nine o’clock, all I could hear was weather, which was not disheartening but luxurious. It meant I could spend at least an hour over breakfast – in bed, of course. Then I wrote a little, read for another hour and watched the rain sweeping across the hills.

Today’s storm is the kind of late-autumn weather that in the old days, before they were almost netted out of existence, drove great shoals of cod towards the shore. But even the most enthusiastic codders, like the few I used to know back in the 70s, wouldn’t have been able to fish today. During a break in the deluge I put on my big coat, hat and boots and went down to look at the drama. It made last evening’s sea look like a rippling pond – all of it was peaking and downbursting and frothing simultaneously, thunderous and colossal, and when the waves whumped into the beach, scattering pebbles, there was a Richter-scale vibration. Although the tide was at half flood, the surf almost reached the cliffs, and I spent a dangerous but happy half hour dodging and splashing. Looking along the beach was like staring along a misty road that was being continually sliced across with tongues of white flame. The surf didn’t retreat after sweeping forward; it just melted like snow through the stones in a matter of seconds.

As I skipped about, there seemed to be an optimistic brightening in the general grey, but it was a false promise. The cliffs to the right and left had only been visible through the flying mist for a few hundred yards, but as the sky darkened once more they seemed to close in around me. Then the rain came back, horizontally out of the south, and the wind threatened not only my hat, but also my coat. I turned my back on it and flew up the path, across the field and into the amazing stillness of the cottage. At about five in the morning I woke suddenly to a peculiar lack of sound. The silence outside was so intense I thought I’d gone deaf in the night. I pulled back the curtains and could immediately see a skyful of stars. The storm had charged off into the north, leaving everything but the leaves (as I would discover when it got light). Something was glinting brightly through the almost invisible trees and I had to go to another window to see that it was just the morning star – Venus. But it was so radiant it didn’t seem quite possible.

At nine o’clock the sun climbed over the hill to the east and, after the essential pot of tea, I went again to look at the sea from the cliff. It was in a different dimension to yesterday. The surface was smooth, with a blue so dark it was almost black. The curved horizon was sabre sharp, yet, looking through my binoculars, there was a pale mirage, like a thin line of mist, running beneath the long peninsula 10 miles to the east.

I went down to the beach and the benign calm made me laugh after yesterday’s violence. The waves were small and quiet, the wind having swung right round to the north-west. The sky was cloudless, but after 30 hours of vigorous stirring the water was thick and milky – hardly perfect conditions for lure-fishing. However, with the mackerel I’d kept in the fridge, at least there was plenty of bait.

I didn’t, though, run straight back for a rod and reel; first I had to finish some writing that I’d begun yesterday – and the time, which usually extends wonderfully when I’m on my own, took me all the way to four o’clock before I noticed it. Yet the sea was still calm and the sky clear when I eventually made my first cast.

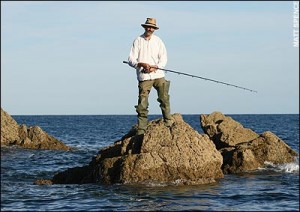

The tide was gently rising, there was a negligible current, and I could keep a strip of mackerel on the bottom with just half an ounce of lead. Having cast, I wedged the rod between two rocks and settled down to the next pleasant chore: tea making.

As I sipped and waited for a bite, a procession of very slow, purple clouds appeared along the horizon, but they’d hardly sailed a mile before the sun sank into its own reflection, allowing the crescent moon to grow out of the blue.

A gull came flying low across the surface to be suddenly revealed as a peregrine falcon, which fluttered on to a ledge in the gorse halfway up the cliff behind me. I got the binoculars focused and it was staring back at me with eyes that had the same fierceness as those of a bass. The afterglow fades quickly in late autumn, yet with the moon directly ahead of me it didn’t get properly dark. But where were the fish? I was sure I’d catch all kinds of different species after yesterday’s riot. Maybe the bait was a bit stale for bass, though there were plenty of less fussy eaters in the sea. I reeled in, re-baited and re-cast, keeping hold of the rod as now it wasn’t so easy to see.

I didn’t really care that there were no fish on such a perfect evening. Then I felt a quick solid tug. It seemed miraculous that in all those thousands of acres of dark water something had found me. It tugged again, then slowly pulled the rod over and I struck into a fish that thudded around for a moment or two before flapping in on a wave. It was only a dogfish, but I liked his sharky profile in the moonlight, and the small lizard eyes.