James Crumley – October 12, 1939 – September 17, 2008

Back in January, James Oldham wrote here about his friend and mentor Brian Case. Yesterday, James and I had lunch with Brian. I had met him only once before, in 1994, when in my capacity as publicist for Primal Scream, I managed to somehow convince him to interview Bobby G for a Time Out cover feature. I say ‘convince’ him for that really was the case, Brian, being a jazz head was no lover of rock ‘n’ roll. It was my indulgence really. You see, I am a huge fan of Brian Case. Back then, his writings on music, books and films were magical gateways in to unfamiliar territories.

Before you wonder why a gentleman that is still very much alive – and still very much an inspiration – is hi-jacking some dudes obituary, I will get to the point. Brian Case turned me on to James Crumley and yesterday he informed me of his passing. Full circle. Dots joined. Sad shit.

Below are words and memories from John Williams. A decade or so ago John interviewed Crumley for his book ‘Into The Badlands’. The first thing Crumley told him was (that) “Alcohol wasn’t invented by accident you know…”

I’ll drink to that. (JB)

Hard to believe I’m the age now that Jim was then

Home? Home is my apartment on the east side of Hell-Roaring Creek, three rooms where I have to open the closets and drawers to be sure I’m in the right place. Home? Try a motel bar at eleven o’clock on a Sunday night, my silence shared by a pretty barmaid who thinks I’m a creep and some asshole in a plastic jacket who thinks I’m his buddy. (The Last Good Kiss)

It’s a dangerous myth, the hard-drinking artist. Chances are, when you meet some guy who writes about lowlife drunks and whores, bad guys and worse places, they’ll be drinking Perrier water and telling you how they won their battle with the bottle just in time. Which is, of course, good to hear. It can also be ever so slightly boring.

“Alcohol was not invented by accident. It was invented by people who needed a drink!” Meeting James Crumley is by no stretch of the imagination boring. After a day of trekking round Paris looking for a hotel room, any hotel room, and ending up in a fleapit that would win the Franz Kafka award for gratuitously depressing ambience, it was more than a relief to find a man who still likes a drink.

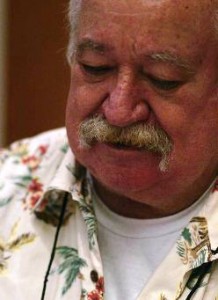

James Crumley is a big man, not tall but powerful with a spreading gut. Greying now, he walks like a man who’s worked physically hard for a living and talks with the care and courtesy of an English lecturer from a college in the Deep South. The contrasting impressions are about right, James Crumley is an ex-roughneck and football-player whose few novels establish him as America’s greatest writer in the Hemingmay tough-guy tradition. Better than that, even; Crumley’s novels are shorn of Hemingway’s macho excesses and his heroes are flawed to a point at which redemption is less than a certainty. Their world is an America that has fucked up to the max.

Drinking with Crumley is not something to be entered into lightly. We started early, dispersing the day’s irritations. Mid-evening Crumley is taken off to a dinner party with several men named Francois who constitute the French roman noir establishment – Hammett lives forever in the Sorbonne. I go to meet a woman named Isabelle who has a bathroom crammed with American hard boiled fiction and wants to know about the roman noir in England. I do my best and she tells me stories about meeting a jet-lagged James Crumley on the train to Grenoble for a crime fiction conference (the reason for his presence in France) and their subsequent discovery that free champagne was on tap in the bar. Later she drops me at Crumley’s dinner party and Crumley, myself and one of the Francois decide to get a drink. We end up in the Bar Americain of a faded hotel near the Gare De Lyon and start on whisky with beer chasers. Francois disappears after the first one, and finally, round about midnight, we get down to the interview.

James Crumley is 49 years old and the author of four novels, one book of short stories and several screenplays that haven’t been made. The first novel, One To Count Cadence (‘a very political novel that didn’t pan out’) was written in the ’60s and is an atypical Vietnam story. The other three, The Wrong Case (‘a very personal detective novel’), The Last Good Kiss (‘a novel about the failure of art in the form of a detective novel’) and Dancing Bear (‘in which I went back towards politics’) are crime fiction of a sort.

The Last Good Kiss, in particular, is probably the best private eye novel written by anybody. The private eye, C.W.Sughrue, is a Texas redneck, an ex-football player and army veteran, a man who needs to keep moving and drinking to deal with the emptiness and the badness of life. His biography has certain similarities with Crumley’s:

“I grew up out in the country in South Texas. My only sibling was ten years younger than me. My father worked in the oilfields, my mother was a waitress. I was lucky, during the war, to live in New Mexico so I grew up with Mexican Americans and I didn’t have that Texas prejudice when I moved back there. My home town is 65% Chicano. My parents taught me to be polite to everybody no matter what colour they were. I grew up wearing chickenfeed shirts to school and the only reason I had shoes was because my mother always insisted I wear shoes. I’d hide them under the cattleguard before I’d catch the bus and I’d go to school barefoot. We were country people. My mother wouldn’t go to church, she sort of insisted I belong to a church and she would take me to Sunday School, and then she would come and pick me up, but she wouldn’t go into the church because she felt that people might make fun of her. This was in a town where the richest people who belonged to the Baptist church made 3,000 dollars, maybe! Her father was in prison, my father never finished high school…”

“Its nice now, I’m 49, to feel its O.K. to be an outsider, all through my youth I always wanted to belong. I was a juvenile delinquent, a football player, I was on the student council, I was on the yearbook staff, I was in the army, I went to a good college on a scholarship. I went back to college on a football scholarship, I played everything but quarter back, mostly I was a linebacker. I grew up learning to run into people at high speeds. I only quit playing flag football, which is a version without pads, when I was 37.. I broke my nose the last time and I stick to softball these days”.

Fast, funny and bleak, The Last Good Kiss begins with Sughrue chasing an alcoholic novelist called Abe Trahearne through a trail of bars across the American west, (the research for this coming from Crumley’s own declared fondness for going off on ‘D & D’ – that’s Drinking and Driving – binges). Catching up with Trahearne in a bar with a beer-drinking bulldog in Southern California, Sughrue and Trahearne end up going on a quixotic errand to track down the barkeepers missing daughter, ten years gone. What transpires is the unveiling of a complex network of jealousies and treacheries, of lives being wasted out of guilt or greed. Crumley may not be an autobiographer but it is easy to see his shadow, both in Sughrue and also, self-laceratingly, in the figure of Trahearne, a big man whose problems with his ex-wife and his inability to write more than three novels in twenty yeas are echoed in Crumley’s life – four ex-wives and four novels in twenty years. If something like Sughrues toughness animates Crumley, then it is something like Trahearne’s self-pity that he is most at pains to avoid.

I found myself chasing ghosts across gray mountain passes, then down green valleys riddled with the snows of late spring. I took to sleeping in the same motel beds he had, trying to dream him up, took to getting drunk in the same bars, hoping for a whiskey vision. They came all right, those bleak motel dreams, those whiskey visions, but they were out of my own drifting past. As for Trahearne, I didn’t have a clue. Once I even humped the same sad young whore in a trailer-complex out in the Nevada desert. She was a frail, skinny little bit out of Cincinnati, and she had brought her gold-mine out west, thinking perhaps it might assay better, but her shaft had collapsed, her veins petered out, and the tracks on her skin looked like they had been dug with a rusty pick. After I had slaked too many nights of aimless barstool lust amid her bones, I asked her again about Trahearne. She didn’t say anything at first, she just lay on her crushed bed-sheets, hitting on a joint.

“You reckon they actually went up there to the moon?” she asked seriously. (The Last Good Kiss)

The Wrong Case and Dancing Bear both feature a failed P.I. called Milo Milodragovitch. Milo is a coke and booze addict marking time till he reaches the age of 52 and inherits his alcoholic suicide father’s fortune, he’s a self-made failure who at least has sympathy for those souls even more fucked-up than himself.

Crumley is there in Milo too, a cultured man running to a beer-gut. “He comes from the good side of my unconscious, at the worst moments of my life I think ‘I can’t be a horrible person because I invented Milo’. He takes care of things, he takes care of all the drunks in the town, he’s kind of a saint. None of Milo’s background is mine. but I’m sure it’s somehow connected metaphorically, in the search for the lost father. When we came back from the war my father was off working all the time in the oilfield and I never saw much of him. He was a very quiet gentle man and my mother was a very forceful violent woman so I got an atypical American upbringing. I’m sure the things I write about Milo and his father or Sughrue and his father come out of my feeling when my father died 13 years ago. But none of the experiences are mine, I’m a writer not an autobiographer”

On the third morning when I sat backward on the toilet lid in the Eastgate chopping up the last of the cocaine, I heard the bathroom door open, so I stopped the click of the razor blade on the porcelain. But somebody kicked the stall door and the latch popoed and whistled over my head, them the same somebody grabbed my collar and jerked me off the stool, stood me against the wall, and started slapping me, Jamison.

“Aren’t you a little out of your jurisdiction, sir?” I said slumped with the gigggles.

Holding me up with one hand, Jamison brushed all the coke to the tile floor, and I whimpered, and then he opened the toilet lid and pulled my face toward the bowl as if it were a mirror where I might see myself. “look at that,” he said, shoving my face closer to the bloody froth. “Janey says you been puking blood for two days“. (Dancing Bear)

Dancing Bear is a book that manages to laugh at self-destruction. It’s full of a terribly black comedy, but it also shows signs of redemption. Milo may be terminally screwing up, but he is at least determined to do what he can to make the place he lives in habitable for the forseeable future. Dancing Bear brings Crumley’s environmental politics to the fore, the bad guys are engaged in dumping toxic waste across the States, not least in Milo’s own back yard, on land sacred to the Benniwah Indians. Crumley’s own political involvement dates back to the ’60s and the Civil Rights movement

“In my most political days when I was in the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), what I liked best about it was that middle class kids discovered how the police had been treating blacks and Chicanos and poor people all the time. Suddenly middle class white kids from Evanston Illinois were getting their heads busted. I think it changed the way America looks at itself. It was a good time, it was a revolution that failed but made some significant changes.” As the ’60s wore on, though, the pitch of Crumley’s involvement slackened, “I was ready for revolution at the point of a gun then I realised I didn’t want to kill anybody. It took the edge off my politics and I backed away somewhere in the early 70s. I stayed active in the Vietnam veterans against the war. I donate money for environmental things, I try to save what’s left of the west, Mostly its money and time whereas in the 60s it was passion. I’m not sure which is better. Once you discover that you’re not going to blow shit up….”

Today James Crumley lives in Montana, in the American North-west, the area in which his three crime novels are set. “I live in Missoula. It’s a small town at the bottom of a lake with a lot of writers and a depressed economy. I first came there in the ’60s when I got a teaching job there. The States is in many ways an unforgiving place, they don’t want you to be different, if I go someplace where no-one knows who I am, I tell them I’m independently wealthy, living off a settlement from the phome company cause they ran over my foot, I won’t tell them I’m a writer. In Missoula it’s O.K. to be a writer, you get some of the respect you always find in European countries or Mexico and South American countries. You can cash a cheque anywhere in Missoula”.

For the last ten years or so Crumley has made most of his living in Hollywood writing screenplays for films that don’t get made (apparently this is the secret of success for a screenwriter – as long as nothing actually gets made your reputation will remain high since you’ve never been associated with a flop). At the moment he’s working on a new draft of one that looks like it might be made, Judge Dredd the movie. At this stage he isn’t keen to talk about it too much but it seems likely that, if made, the superhero stereotype will never be the same again. Meanwhile the chance to get away from Hollywood’s frustrations has arrived in the shape of a fat advance from his new publishers for a new Sughrue novel to be set in Mexico and South Texas. This he intends to finish by next summer before spending the rest of the advance on a year in Europe. For now a new book of short stories, Whores, is just out in the States.

Towards 1 a.m. we finish the interview as the hotel bar closes around us. As we emerge on the street, James Crumley says he thinks he might like one more drink before returning to his hotel. A fool to myself, I agree that one more drink can’t hurt. Two hours and somewhat more more than one drink later that bar also closes and, around six hours before I’m due to catch a plane back to London, I stagger off in the general direction of my hotel. James Crumley is a major writer with the swollen knuckles of a former prizefighter, a couhtry music aficionado who used to play poker with Nelson Algren, and a dangerous man to go drinking with.