Bill Brewster pays his respects to Norman Whitfield, who died last Tuesday;

Norman Whitfield was black music’s first auteur. His work as a studio producer, firstly at Motown where he was a staffer for over nearly 15 years and later independently, revolutionised the production of soul music. Alongside Sly Stone, a significant influence on Whitfield, he deconstructed more traditional soul structures by fusing elements of psychedelic rock and drenching the studio in acid. He was also a gifted songwriter responsible (usually alongside co-writer Barrett Strong) for several of Motown’s early hits.

Unlike most of his Motown counterparts, Norman Whitfield grew up in Harlem in New York City and only wound up in Detroit when the family car broke down on the way back from a trip to California. They never left. Tall and slim and outwardly reserved, Whitfield was nevertheless streetwise and before the royalties began to flow for his first big hit, I Heard It Through The Grapevine, his main source of income was as a pool hall hustler.

He worked at Motown from the late 1950s, doing everything from cleaning the studio, helping assess songs passing through Berry Gordy’s legendary Quality Control Dept to banging the tambourine for Popcorn Wylie and the Mohawks. Any spare time he had would be spent hanging out on the studios watching Gordy’s producers running the Funk Brothers through their paces. His first notable success was as co-writer of Marvin Gaye’s Pride And Joy (with Berry Gordy and Mickey Stevenson) and he later went on to work with Marvin on two late 60s albums, MPG and That’s The Way Love Is, that pointed towards a new direction for Gaye (although the pair had a fractious relationship with Whitfield’s domineering studio presence rubbing up against Gaye’s more laconic approach).

It was an amazingly fertile time for songwriters at Motown with Pam Sawyer, Ashford & Simpson, Holland, Dozier and Holland, Whitfield and Strong, Harvey Fuqua, Johnny Bristol, The Corporation and Smokey Robinson all competing for the ears and attention of Gordy. “Berry thought like an oil man,” claimed Marvin Gaye. “Drill as many holes as you can and hope for at least one gusher. He wound up with a whole oil field.”

Whitfield scored two significant hits in the mid Sixties with The Velvelettes’ Needle In A Haystack, another co-write with Mickey Stevenson (which he also produced) and I Heard It Through The Grapevine, which was a hit first for Gladys Knight & The Pips but was, in fact, recorded by the Miracles, The Isley Brothers and Marvin Gaye prior to this (the Gaye and Gladys version separated by only a month). When the Marvin version was released after much canvassing by Whitfield and pressure from radio DJs who’d picked up on it as an album track, it became Motown’s first number one and their biggest selling single of the time. Whitfield also wrote and produced one of his classic songs-with-meaning, Friendship Train, for Gladys Knight & The Pips.

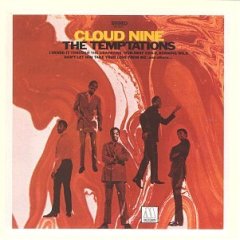

His best work at Motown was primarily done with one group, though: the Temptations. Smokey Robinson had guided their music until Whitfield wrested control from him after the relative commercial failure of Get Ready. His first single for them, Ain’t Too Proud To Beg, written with Eddie Holland, was their first number one R&B hit. Within two years he went from producing songs like the smoochy classic I Wish It Would Rain to the groundbreaking Cloud Nine. “When that came out the establishment was a little stunned,” said The Tempts’ Otis Williams, “They were used to us singing Ol’ Man River and Ain’t Too Proud To Beg but suddenly we were into a heavier kind of song.”

Seen through the kaleidoscopic view of the Sixties, Cloud Nine advocated drug use as a balm to cope with the harshness of inner city life. It was in stark contrast to the aspirational Motown approach but brought the label nearer to African-Americans (it’s probably true to say that, although Motown was wholly black owned and run, it was the multiracial Stax that had the hearts and feet of young black America). It was the start of a series of episodic songs – Papa Was A Rolling Stone, Run Away Child, Running Wild, Ball Of Confusion, Psychedelic Shack that drenched the Temptations in paisley-patterned blotter. Whitfield’s songs went from concise 2’ 30” masterpieces to yielding mini-operas straight from the heart of Watts, Harlem and Cabrini Green. The Sound of Young America got serious. You can hear his influence in the work socially conscious work of Gamble & Huff or Curtis Mayfield and the lavish productions of Isaac Hayes and Barry White.

Whitfield worked with the Temptations solidly for about 5 years before his obsessive and often dictatorial style led to a revolt by the band and his replacement after the 1990 album in 1973. Whitfield left Motown the same year to form his own label (through Warner Bros.), the modestly-named Whitfield Records and took with him the Undisputed Truth. He had promised them a hit within the first three singles and did so with Smiling Faces Sometimes, a magnificently paranoid song in the vein of the O’Jays’ Backstabbers (the Temptations recorded a somewhat better version on the Sky’s The Limit). They made a succession of really good, but uncommercial albums that developed Whitfield’s interest in UFOs, joining a lineage of black artists inexplicably obsessed with space travel, Egyptology and Martians that begins with Sun Ra’s landing from Saturn and winds up with Afrika Bambaataa overdosing on Bacofoil headgear. The Temptations were also roped into to his space dystopia with the uneven 1990, an album that also featured almost the whole line-up of a new set of protégés: Rose Royce.

Whitfield’s accomplishments with Rose Royce outshone the Undisputed Truth with the Car Wash LP. He had already recorded an album with Rose Royce when approached by movie director Michael Schultz, whose overtures towards the Temptations and Undisputed Truth were resisted in favour of his new charges. The subsequent soundtrack, like Superfly before it, outshone the actual movie, a turgid cheapie that cost $2m. to make and inexplicably grossed $20m.

Rose Royce never reached the same heights again, although again, they released a series of very good soul and disco albums that did well on dancefloors if not the Billboard Top 40. In fact, Whitfield never reached the same heights again, either. By the end of the Seventies his Whitfield label had gone and he returned to Motown in the early 1980s. In 2005 he was prosecuted by the IRS for failing to report royalty income and was sentenced to six months’ house arrest.

Norman Whitfield turned soul albums into works of art. A true auteur who used the studio as an instrument, he transformed black music from a mainly 45s artform into LP-length epics. In doing so, he actually helped hasten the end of a particular style of black radio (the Honkers and Shouters of the Jocko Henderson school) and ushered in a smoother, new sound as exemplified by Frankie Crocker. He also ushered in a new, more mature, era at Motown with adult themes and risky subject matter. “Whitfield was tremendously important to the development of the company,” said Ralph Seltzer, a high-ranking Tamla Motown executive. “Norman should have been given his own label. Unfortunately, granting that sort of autonomy was not Berry’s style.” He is probably circling the planet now in an Intergalactic Spaceship with only Sun Ra and Nefertiti for company.

read more Bill at the excellent ‘DJ History‘ website