by Simon Reynolds, from today’s Guardian

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Radiophonic Workshop, the BBC’s experimental unit for electronic sound. It also marks the 10th anniversary of the workshop’s death after a long period of decline. But almost as soon it was gone, it began to assume cult status. A Radiophonic ghost began to haunt the peripheries of pop culture, audible initially as an influence on “retrofuturist” groups such as Boards of Canada, Broadcast and Add N to (X). In the past five years, there has been a steady flow of Radiophonic-related reissues from labels such as Mute, Rephlex, Glo-Spot and Trunk; a BBC4 documentary, Alchemists of Sound; and a South Bank symposium organised by Saint Etienne’s Bob Stanley. There have been two plays about the workshop’s Delia Derbyshire, and when Doctor Who was relaunched in 2005, unfavourable comparisons were made between the Radiophonic team’s original electronic music and the orchestrated flatus of Murray Gold’s updated version. This summer, the Southbank Centre held a symposium on Daphne Oram, the workshop’s co-founder, and there was news about the discovery of a huge cache of unreleased material by Derbyshire, the workshop’s most brilliant composer. In November, Mute is set to issue a double CD compilation, 50th Anniversary Retrospective, including nuggets never before released.

The workshop is still best known for Doctor Who – not just the theme tune, but the array of sound effects that made the show so creepy, from spooky winds evoking the poisonous atmospheres of alien planets to the grotesque squelches of a slime monster crawling up Sarah Jane Smith’s leg. Yet Doctor Who represented just a tiny fraction of the outfit’s output, which covered radio plays, TV series and educational programming, countless jingles and theme tunes, and a number of major productions initiated by the workshop itself. Especially through its contributions to programmes for schools, the workshop filtered into the collective unconscious of young Britons during the 60s and 70s. “We were part of your life,” says Brian Hodgson, who created “special sound” for Doctor Who for its first 11 years – including such “classics” as the Tardis taking off and the voice of the Daleks. The workshop could be one reason why Britain has played such a vanguard role in the rise of electronic music, from 80s synthpop to 90s techno-rave.

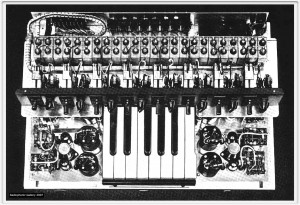

The workshop opened for business in a couple of rooms at the BBC’s Maida Vale complex on April 1 1958. For several years before that, Oram had been pushing for the BBC to start its equivalent to French national radio’s audio research unit GRMC, where the founder Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry pioneered the tape-editing techniques of musique concrète. Unlike its Paris counterpart, the workshop began with a minuscule budget and meagre equipment. “It was mainly secondhand – stuff the BBC had thrown out, peculiar devices that were useless until the workshop’s original engineer, Richard ‘Dickie’ Bird, managed to get them working again,” says Hodgson. Although the project was Oram’s brainchild, she soon left. Concerned that working with experimental sound could result in brain disturbances or madness, the powers that be decreed people could work there for only three months. The rules were soon changed, but too late for Oram, who resigned from the BBC and built an independent studio to pursue her dream of a system that could enable the composer to “draw” sound.

The BBC’s music department was suspicious, verging on hostile, about the workshop’s creation. The push came from the drama department. The workshop “was much more part of the 50s theatre revolution than the music revolution”, according to Hodgson, who had trained as an actor before joining the BBC. The term “workshop” came from theatre, he says. “It was a trendy term in the late 50s, but if the unit had been started a decade later, during the era of arts labs, it’d probably have been called the Radiophonic Laboratory.”

Through the 50s and into the 60s, the drama department encouraged new writers and formal experiments of all kinds. Producers started to mess around with the newly available reel-to-reel tape machines that were replacing the 78rpm platters on to which studio managers had recorded sound effects. “If you accidentally left the fader open on a tape machine, you’d get this dreadful howl-round sound,” recalls the chief engineer Dick Mills. “But if you could control it, you got peculiar echo effects that created a kind of disembodied voice, which could be used to portray a character in a radio drama thinking aloud, or undergoing mental distress.” In an increasingly chaotic environment of studio managers borrowing tape machines and forgetting to return them, the decision was made to create a unit dedicated to providing incidental music and sounds for anybody within the BBC who required them.

One of the gems on The John Baker Tapes, released in July, is Baker’s appearance on an early 60s edition of Woman’s Hour to explain how he made a whimsically futuristic jingle for the show’s “reading your letters” segment. A single glug from water poured out of a cider bottle supplied the timbre for the main melody, the dry pop of a cork being pulled out of another bottle served as percussion. Altering the speed of the tape varied the pitch and created a couple of octaves of notes; each individual note was then sliced and spliced into a sequence. Hours and hours of intricate work resulted in a jingle arresting enough to get readers writing in about the tune.

On the continent, state-run stations such as Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française, Westdeutscher Rundfunk and Radio Italia funded their own sound laboratories dedicated to exploring the new tape-editing techniques and grappling with primitive devices, such as ring oscillators, for generating pure electronic sound. But whereas Bernard Parmegiani in Paris or Karlheinz Stockhausen in Cologne were allowed to engage in pure research, the workshop’s activities were always tethered to the practical. The team had to earn their keep with futuristic jingles and wacky noises. “We weren’t composers flying our own kites,” Mills says. “Any experimenting we did was always within the context of someone’s programme.” It was craft, not art, with an aura redolent of an amateur cobbling together Heath Robinson-like contraptions in the garden shed. “Because we’re not experts,” the workshop’s indulgent manager, Desmond Briscoe, would say, “we don’t know what we shouldn’t be able to do.”

Alongside its bodged quality, early Radiophonic output was often suffused with English surrealist humour. There was a comedy connection: The Goon Show was one of the workshop’s early clients, with Mills creating such well-known effects as “Major Bloodnok’s Stomach”, an absurdist eruption of gastric turbulence that signalled the entrance of “an Indian officer gentleman with a passion for hot curries and loose women”. According to the workshop composer Paddy Kingsland, “Spike Milligan virtually wanted to take the place over; Desmond Briscoe talked of having to fight him off.”

Another difference between Radiophonic and its peers in Europe was the prominent role of women, from the co-founder Oram, through early composers such as Derbyshire and Maddalena Fagandini, to later figures Glynis Jones and Elizabeth Parker. Derbyshire had first sought employment at Decca Records, only to be rebuffed with “we don’t have women in engineering or technical roles”. By contrast, the BBC had a remarkably progressive policy in terms of equal employment opportunities. This went back at least as far as the second world war when, Hodgson says, “the BBC was virtually run by women, because the men were off fighting”.

Derbyshire is easily the most famous alumna. Her striking looks (“tall, with beautiful auburn hair”, recalls Hodgson) and erratic life (heavy drinking, bouts of depression, eccentricity) contribute to the mystique. Mostly, though, it’s about the remarkable music. A gifted mathematician, she plotted out her pieces with a scientist’s precision. “Blue Veils and Golden Sands”, music for a documentary about the Tuaregs of the Sahara and her most celebrated piece after the Doctor Who theme (written by Ron Grainer, but transformed by Derbyshire’s electronic realisation), involved analysing a real-world sound source into “all of its partials and frequencies”, then reconstructing it using the workshop’s battery of oscillators. The original sound was almost comically prosaic: a standard-issue “tatty green BBC lampshade”, she recalled in one interview, which gave off an ethereal bell-like sound when struck.

The piece also involved Derbyshire’s treated and chopped-up voice and “slowed-down camel groans that were looped and filtered”, says the workshop archivist Mark Ayres, who has compiled the forthcoming CD set. Ayres has been slowly cataloguing and digitising the 4,000 reels (which contain approximately 3,000 hours) in the workshop’s chaotic library, which once occupied three rooms but was shunted into a single room in Maida Vale during the unit’s twilight years. Only a diehard fan would take on this labour of love, which involves painstakingly restoring tapes that have dried up or gone sticky because of myriad edits.

Thanks to Doctor Who’s popularity from the early 60s onwards, intrigued pop musicians began to pay visits to Maida Vale, including Pink Floyd, Jimi Hendrix and Rolling Stone Brian Jones. Paul McCartney approached Derbyshire with a view to her providing electronic backing for “Yesterday”. It never happened, but later she did the music for one of Yoko Ono’s experimental movies, Wrapping Piece. By this time the prim-voiced and “impeccably dressed” Derbyshire of the early Radiophonic days had thrown herself into the swinging 60s, adopting what Hodgson fondly calls her “gypsy grandmother mode” of clothing and going through, according to Mills, a period of “funny-coloured tobacco, and snuff, and cider”. She and Hodgson formed an electronic research-and-performance entity called Unit Delta Plus, in collaboration with the inventor Peter Zinovieff, who set up a studio that was far better equipped than the workshop. After working all day at the BBC, they’d head down to Putney to work all evening there.

The neophiliac mania that had buoyed the 60s was crashing hard by 1970, and the Radiophonic Workshop wasn’t immune. The new synthesisers superseded tape-editing, and the balance shifted from “soundsmiths” (including Hodgson and Mills) to “tunesmiths” – new recruits such as Kingsland and David Cain who had played in rock bands. The workshop’s services were more in demand than ever. Local radio stations were starting up all over the country and they all needed jingles. Mills recalls Cain doing one for Radio Sheffield using the sounds of stainless steel cutlery, “because every regional station liked to reflect the local industry”. Television’s hours and channels were also expanding: Kingsland did the music and weird noises for the chilling children’s series The Changes, set in a Luddite near-future when people turn against technology, and later scored both the radio and TV versions of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

In the 80s, the Radiophonic Workshop embraced the new digital technology of sequencers, samplers and MIDI (the machine that enables musicians to synch up all kinds of electronic devices). When Hodgson returned to take over from Briscoe as manager, his first priority was to modernise and re-equip. In addition to the huge demand from television, the workshop was initiating large-scale productions of its own, such as Peter Howell’s Inferno Revisited, a reinterpretation of Dante.

Yet while the 80s were in many ways triumphant years for the workshop, the music that Radiophonic cultists cherish tends to be from the early, makeshift days, when magical results were achieved by the most rudimentary means: tape, razor blades, found sounds. By the mid-80s, electronic music gear could be found in any Dixons. The function and future of the workshop had become cloudy. “In a way, our success created the seeds of our destruction,” says Hodgson. “We’d got people used to electronic music and we’d pushed the technology that made the do-it-yourself thing possible. Nowadays a kid in his bedroom has more technological resources than we had for the first 25 years of the workshop. It’s the democratisation of music.”

In the 90s, John Birt introduced reforms of the BBC designed to create a kind of internal market. For the workshop, “producer choice” – the slogan of the day – meant “the big programmes could hire anybody they liked from outside”, Hodgson explains. “As a result, the workshop sort of collapsed.”

Hodgson emphasises the workshop’s radio and TV output for schools. He remembers a programme that taught geography by using the idea of a magic carpet whizzing across the globe. “If you’re a kid,” he says, it can only be good for your imagination to hear the sound of a magic carpet taking off.

The workshop fitted the Reithian concept of what a national broadcaster should be about: expanding the cultural horizons of the general public. Among the many contemporary outfits influenced by it is the London-based Ghost Box label. Julian House, the label’s co-founder, aligns the workshop with the postwar spirit of planning and building for a better future that encompassed modernist architecture and urban planning, the Open University, and Penguin and Pelican paperbacks. “It’s now unthinkable,” he says, “that a public body could produce for the masses such avant-garde, forward-thinking, sometimes difficult music.”