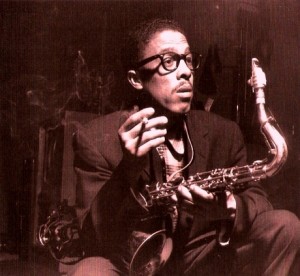

April 24, 1928 – July 25, 2008

The reaper took old Johnny a few months back now, but here, Brian Case pays his respects;

Tenor saxophone giant, Johnny Griffin, died this July aged 80. Not bad for an American black in the jazz life, a non-stop ball of fire throughout a half century performing career. His sound is unlikely to permeate the coffee bars like Miles or Coltrane or Getz or Brubeck. He was too frantic for ballads, his tone too volatile to caress a melody, and his energy too impatient. His own compositions tended towards the frankly carnal – ‘Soft and Furry’, ‘Let me touch it Baby’, ‘Lady Heavy Bottom’s Waltz’ – or the unannouncable – ‘the JAMFS are coming’, JAMFS an abbreviation of jive-assed muthafuckers. Not much there to go with your cappuccino.

I first saw him at the Bull’s Head, Barnes in the early sixties. His reputation preceded him. Blue Note recordings like ‘Introducing Johnny Griffin,’ The Congregation’ with its early Warhol cover and ‘A Blowing Session’ in which he outblew John Coltrane and Hank Mobley, gave an early picture of the fastest tenor ever and a player moreover, whose imagination kept pace. Everything he played at the Bull’s Head was fast, or became fast, and he clapped triplets out of some inner dynamo when he turned it over to the band. Our own Tubby Hayes was in the audience and gestured to Griffin that he’d like to sit in. Griffin didn’t know him then. If you can, his face said, eyebrows raised. Tubby, to Griffin’s delight, could cut it. ‘Yeah, Fatty!’ he yelled, well-meant, but a bit of a pisser for the Tubbster.

Years later, after the two tenors had played together in the Kenny Clarke – Francy Boland Big Band, Griffin recalled,’ that was my buddy, Tubby Hayes and Jimmy Deuchar,. Why, they put us out of all the nice towns in Switzerland. Yeah, the dirty Trio. Every place we’d be there’d be a riot! I imagine we were pretty out-of-hand because everybody loved the booze. Talk loud, laugh a little too loudly, disturb all the elderly hotel guests in the rich resort areas. We’d get nice escorts right to the train station, they’d pack our bags and take us right to the train!’

He was a moving party. He worked with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and with the Thelonius Monk at the Five Spot. Those two albums have little of Coltrane’s majesty with Monk, but swarmed all over the great eccentric’s compositions as if they were pie-simple, swung like hell, and introduced the pianist with a mischievous quote from ‘Here comes the Bride’, Griffin was technically unassailable. His bebop background never left him wrong footed in any musical situation, and his urge to play was furious.

He had one of the most exciting styles in jazz, and although he was no innovator, he patented a personal way to rip the houses up. Idea crowds idea, each tightening the ratchets of tension, the tone edged with near-hysteria. He’d depth-charge to the cellar of the low B-flat like an untethered elevator, leaving the listener’s stomach back with the mezzanine to be unceremoniously recoupled to a flashing ascent. A push in the solar plexus from a flat blatted note, a lulling legato and it’s up, up like a siren warning to find the crest abruptly cuffed aside, and a gulping gap in one’s expectations. He could wring you out. How did he arrange numbers with the great snapping drummer Philly Joe Jones I once asked him. He looked baffled. “I’d kick his bass drum, kick it, WHAM!’ ‘I’d say ‘Get in there, muthafucker!’ Like Bird’s number says, ‘Now’s the time’, or Dexter Gordon’s album, ‘Go!’ Griff was present tense.

The two tenor outfit with Eddie’s ‘Lockjaw’ Davis paired dissimilar styles but similar joyous aggression. Jaws was a near honker, as master of the dirty stubbed note and impacted holler. They goaded each other on, and recorded a string of wild albums. Although Griffin spent his last 40 years in Europe, he continued to activate any local band he encountered. When Norman Granz’s jazz package arrived in Montreux, Griffin sat in with Count Basie and Roy Eldridge and showed everybody up. They were there to be merely typical. He never stopped swinging and I loved him for it.

‘Whenever I’m in trouble, I go straight to the music. I go to the piano – BANG! – and blow my horn. It does not let me down. It remains the only constant’.

So was he.