Paolo Hewitt tells a young mod’s forgotten story;

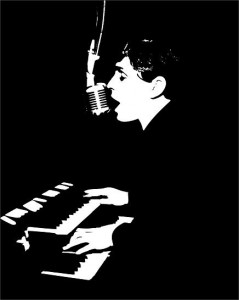

Of course his real name is not Fame, it’s not even Georgie. It’s Clive, Clive Powell, and he was born 26th June, 1943, in Leigh Lancashire. He grew up there, grew up to be one of the most influential, stylish and underrated musicians this country has ever seen. Georgie Fame was the one, the man who created the musical template that many have tried to copy. He put together one of the first multi racial bands and then massively helped popularise black music in the UK. He paved the way for so many musicians and he did so with ineffable cool, ineffable style. He still has that style and I can say that because not so long ago I spent two hours with him in a Soho restaurant and he did not disappoint. Don’t meet your heroes they say and I say, true, but there are exceptions. And Georgie Fame is exceptional.

Georgie began by telling me about how this radio in his family house, how on it, he heard early rock n roll, early r’n’b. It was like meeting Jesus – life is going to change. Forever. The young boy learnt piano and organ, formed a band called The Dominoes, and then set out on the road, playing rock n roll. In 1959 they turned up at a holiday camp and came into contact with the camp’s resident bandleader, a guy called Rory Blackwell.

He liked the Dominoes so much he bought them, turned them into Rory and the Blackjacks, and off they headed for London town, searching for a break.

The band soon split (name like that, what do you expect?) but Rory had a purpsoe. He got Georgie an audition for the impresario, Larry Parnes. Parnes was a big shot at the time, a man who looked after a lot of bands, a man who could make things happen. At the Lewisham Odeon during a soundcheck Fame cleared the stage, sat at his piano and sang Parnes the Jerry Lewis song High School Confidential and within seconds of finishing Parnes had his name on a contract.

Parnes was renowned for believing all his stars should have starry names. At that time he had on his books a Wilde, an Eager and a Fury. All he needed now was some Fame, some Georgie Fame. Thus christened Georgie took a flat in Old Compton Street, opposite a lingerie shop (he still remembers the pink number in the window) and hit the road with dozens of Parnes’s bands, ending up with the British rock’n’ roller Billy Fury who dressed in gold lame suits and smoked a spliff a day.

That gig ended in acrimony so Fame quit and with came him Fury’s band, The Blue Flames. They secured a residency at The Flamingo, a club just up the road from Georgie on Wardour St.

Upstairs from The Flamingo was the Whiskey A Go Go, later it would become the Wag Club. Now it is an O’Neil’s pub. Draw your own conclusions.

At the Flamingo they started playing cover versions of the current r’n’b, Blue Beat and ska songs, learnt from records that could only be bought if you were hip enough to know where to go.

The sound Georgie and his band made was totally authentic. That’s because they were real disciples, dedicated, sensitive to all the music’s subtleties and power. They were the first to show how it could be done. The late great writer Dave Godin lost his friendship with Mick Jagger when he pulled him up for his band’s terrible version of Marvin’s Can I Get A Witness. He could never have levelled the same fire at Georgie and his Blue Flames.

Word on the band spread out, reached a USA army outpost about an hour out of London. Next thing you know these black American servicemen are flocking to the Flamingo, packing the tiny place out week in week out, siding up next to the club’s weekly clientele of Soho pimps, prostitutes and gangsters. They all loved Georgie, especially these servicemen. Every week they would bring him the latest import records they had just got in from their people in the States. George would take these albums home and study them obsessively. (It is how he first came across Mose Alison, the man he most wanted to be.) On Friday night he would visit Austin’s in Piccadilly Circus and buy American Modernist clothes and then come Saturday night he would dress up, hit the stage and play these songs back to the servicemen, note for note, nuance for nuance.

They in turn danced and grooved and after the show had finished lined up to give Georgie and his Flames the compliment they most yearned for – hey man, you sound just like the record.

One night, a knife fight between some disgruntled soldiers erupted and they got themselves banned. No problem. The very next week the Mods moved in and Georgie with his Ivy League look, his cool demeanour, weaved his magic on them..

It was the early 60s and you have to understand just how important this r’n’b music

was to what came later. Everyone in a band, Jagger, Lennon, Burdon, Marriott, wanted to be black. They wanted to sing like Ike Turner or Ray Charles or Marvin or Bobby Blue Bland. They wanted to make music as cool and as deep and as hip as r’n’b. Georgie showed them how. That is why he is so important in the tapestry.

He had luck on his side as well. His voice was beautifully suited to the material, rich, striking and able to cover all points without ever making a false move. You can hear it on his debut album which appeared in 1964, a live recording taken from The Flamingo which is revered to this day. Then, later that year he released a single called Yeh Yeh and it was the making of Georgie. He told me, ‘It was recorded originally by Mongo Santamaria. Jon Hendricks put lyrics to it and recorded it live at The Newport Jazz Festival. I played it up and down the country for months before we recorded it. We were wondering what to do as a single and somebody said, ‘Why don’t you do ‘Yeh Yeh?’ and it went down well.’

See what I mean about cool? Went down well? It went to number one and Georgie was up and running. Hit after hit followed, Get Away, Sunny, the achingly beautiful Sitting In The Park, like I say, hit after hit. Georgie got known outside the r’n’b circle, befriended amongst others the Beatles. One day McCartney rang him. Ringo is ill he told him, we need a drummer to tour Australia, can we take your boy Jimmy Nichol? Course you can said Georgie and he rang Nichol. You got a passport? he asked the young drummer. No came the reply. Okay lad, said Georgie, get yourself down the Post Office, your a Beatle now.

What happened to Nichol I asked Georgie. ‘The tour went to his head,’ he laconically replied. ‘Last time I heard of him he was in Mexico playing psychedelic music. That

was 1967.’

The Sixties was a time of experimentation and drugs but Georgie ever the cool one steered clear. He had his own religion to follow, which is why his success was never vulgar. If it happened, cool. If not, cool as well. He moved into jazz, cut albums with the big band arranger Harry South (later wrote the theme for The Sweeney) and signed a solo deal. Great songs emerged. Hear Peaceful, one of the greatest Sixties singles ever made, or Sweet Thing, The Whole World’s Shaking, Seventh Son, believe me it is class all the way. In the 70s – ill advisedly it might be argued – he teamed up with Alan Price but it never amounted to much. Georgie always was best left to his own devices.

And then it all came to an end. Georgie fell out of style, a style he was never suited to anyway. But he never stopped working, never stopped spreading the word on the glory of the music he adores. (He would have felt a pang at the recent news of singer Alton Ellis’s passing.)He tours the world now, finds himself making records with great admirers such as Van Morrison and he never ever fails to keep the record straight. I saw him at Ronnie’s. He opened up Yeh Yeh by saying, ‘Some of you might think this is a song by Matt Bianco, who sang it in 1980 whatever. No. This song was written by…’

In the Book of Mod , Georgie Fame is Chapter One.

05-sweet-thing