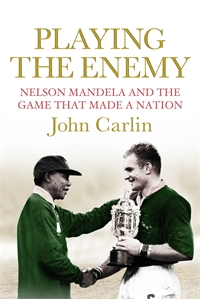

Nelson Mandela and the Game That Made A Nation

By John Carlin (Atlantic Books)

review by Paolo Hewitt

When a man spends twenty seven years in jail he can pick up certain habits. For example, no matter where he is in the world, Nelson Mandela will promptly awake at four thirty in the morning and make his bed. He picked up this habit in prison in 1964 and he has been stuck with it ever since.

In Shanghai, whilst on Presidential business, Mandela was alerted to the fact that the chambermaid assigned to his room had been complaining that every time she went into his room the bed was made. Making the bed was her job, not his.

On hearing this Mandela instantly invited the chambermaid to his room. There he patiently explained himself, profusely apologising if he had caused her any offence. He couldn’t help himself, he told her, but he would try his best from now on.

The story vividly demonstrates the respect Mandela holds for every human being, be you leader or servant and opens up John Carlin’s new book Playing The Enemy, his brilliant account of the seismic events leading up to the 1995 Rugby World Cup Final between South Africa and New Zealand.

Yet this book is not just about the game and the history that preceded it, although those themes are obviously very prevalent. No, this is a book has a higher purpose. This book is about the awesome power of forgiveness and what it can achieve when applied in the most terrible of circumstances. It is how one man and his people managed to rise above colossal resentment and revenge and unite a country in the most impossible and beautiful fashion. It is a story about the incredible potential of the human spirit and how it can flourish in the most impossible of circumstances. And it will move you to tears.

Nelson Mandela was placed in Robben Island prison in 1964. To white South Africa, he was a Communist and a terrorist, viewed in the manner the West currently views Osama Bin Laden. He was a national figure of hate. Yet he proved them all wrong and he got them onto his side. He did so because, apart from many things, Mandela is an astute man. Very soon into his incarceration he realised that his organisation, the African National Congress, could never militarily defeat their white oppressors. He saw that the only way to dismantle the violent and morally bankrupt state of apartheid was through peaceful dialogue. This is why in prison he began studying his enemy in a ferocious fashion. He placed the white South African, the Springbok, under the microscope and began his studies. He learnt their language, Afrikaans, he read their books, and he studied their mentality, how they thought, how they operated. When it finally came time for them to meet and to trade Mandela knew how to play them like an expert poker player.

Soon into his studies of the enemy Mandela quickly grasped the huge importance of rugby to the Springbok. For them, rugby is their obsession, their religion. To the South African blacks it was a stupid game played by wicked men but to the Springbok rugby was all. This is why when he finally became President Mandela quickly lifted the international embargo on the national team and allowed them to play at home and away. It was his way of reaching out to a race who were so distrustful of him that a counter revolution was busy bring planned as he accepted the Presidential nomination.

(What happened to that revolution forms the basis of another highly charged scene in this book)

One of Mandela’s first public acts was to forgive his gaolers and give key Government jobs to those who had served in previous apartheid governments. By doing so, and against all the odds, the great scar of blood and hate that ran through the middle of that beautiful country started to heal.

The climax of the book comes with the 1995 World Cup tournament. Mandela seized on that occasion to bring together the country. He persuaded the rugby team, for example to learn the ANC National anthem so that it could be sung along with the Springbok anthem at rugby games – ( The scene where the team gather to learn a song they previously thought of as a terrorist anthem is one of the most powerful scenes in a book packed with emotion,) and he and his people for the first time ever supported the Springbok rugby team as they tried to overcome the brilliant all conquering New Zealanders.

Mandela’s refutation of revenge after he left prison and began the journey to this match is as astonishing and I wish Carlin had explored that personal angle more, had discovered how Mandela reached such a state of spiritual grace. And what should never be forgotten however is that millions of people agreed to follow Mandela down this path, and in doing so gave the world a master lesson in dignity. They are the heroes as much as their leader, the man I see as our Martin Luther king, our Gandhi

John Carlin is a very good writer whose style is both accessible (you really don’t have to like rugby to enjoy this book) and vivid. His eye for the crucial detail is brilliant and the book’s structure exemplary. He covered apartheid in the ‘80s for Britain’s best paper, The Independent so he knows where the bodies are buried. Literally, in some cases. His skill aside I adore this book because it asks the reader a hugely profound question – do you have the strength to forgive your trespassers? Can you forgive and make peace? Can you cast aside your grievances for the better way?

Mandela and his people did. They forgave murder and violence of an unimaginable scale. This book shows you how they did it. Read it, weep, and let’s all of us learn.