from 1000 novels everyone should read, the Guardian, Friday 23 January 2009

The Rings of Saturn (1995)

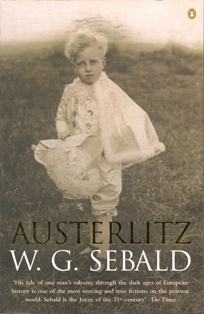

Austerlitz (2001)

No other writer of recent decades has matched the speed of WG Sebald’s ascent to the pantheon. It occurred in a little over five years. The Emigrants, the first book of Sebald’s to be published in English, but the second to have been written, appeared in 1996. Then came The Rings of Saturn and Vertigo, together forming a loose trilogy. Comparisons were made with Borges, Calvino, Kafka, Proust and Nabokov. By the time of the publication of Austerlitz, his masterpiece, in September 2001, Sebald was unmistakably a major European author, and his admirers were already predicting a Nobel prize. Then, on 1 December 2001, Sebald died in a car crash near Norwich.

But Sebald’s reputation has only grown since. This curiously antique stylist has also – at least in England and America – become recognised as one of the most contemporary of writers. His eerie, piebald, polymorphous narratives – with their infrequent paragraph breaks, their wanderingly long sentences, and their embedded black and white photographs – have attracted the attention of architects, poets, artists, psychoanalysts, philosophers, geographers and historians, as well as hundreds of thousands of “ordinary” readers.

The Rings of Saturn describes a summer walking tour down the Suffolk coast, made by a narrator figure who resembles, but is not quite, Sebald himself. Along the way, he tells apparently disconnected stories about the deforestation of Britain, the drowned town of Dunwich, the herring trade and Bergen-Belsen. Gradually, the reader realises that this almost folksy travelogue is in fact a vastly complex rumination on ruination and transience. And that the apparently crabwise motion of the narrative – its near-refusal to proceed – is in fact Sebald’s way of sidling up to some of the most significant questions of modern history: trauma, the Holocaust, repression. The same preoccupations recur in Austerlitz, whose eponymous central character is, like all Sebald’s people, wrecked on the reef of the past.

A measure of Sebald’s stature is his influence. He has already whelped hundreds of imitators, as well as the adjective “Sebaldian” (usually now used to denote anyone who writes long sentences, or who mixes photographs with text). Sebald’s few detractors liken him to the Eeyore of contemporary literature, always grumbling greyly away. But most people who write about reading Sebald use the language of hypnosis or narcosis to describe the effect that his work has had on them. They reach for words like “compulsive” and “mesmeric”; terms that testify to a sense of a powerful brain-magic having been worked, to readers having been forced to think in ways beyond their volition or their control.