Our friend Mick Houghton remembers a man who actually deserved to be tagged as a legend…

In September of 1968 I left home in London to attend Leicester University – like most, I’m sure, because I couldn’t think of anything better to do. It was officially the worst three years of my life. Pretty much all that sustained me in this tortuous time was an obsession with music, mostly American singer songwriters and west coast rock bands like The Byrds, Burritos, Love, The Mothers and Jefferson Airplane. I’d discovered British folk music a few years earlier, particularly Pentangle, The Incredible String Band and Fairport Convention – the big three. I’d seen their prestigious Royal Festival Hall and Royal Albert Hall Shows, and occasionally went to Cousins folk all-nighters where I was lucky enough to catch Jackson C Frank, Roy Harper, Davey Graham and Al Stewart but, hand on heart, I can’t remember seeing John Martyn play early on. Although he arrived a little later on that scene, John Martyn played the folk clubs and had supported Fairport on an a Festival Hall bill I went to but I can only recall Nick Drake, who opened, because he was so jittery and inaudible that I thought he was terrible. John Martyn was the first white solo act signed to Island Records, but his first two records made no impression on me at all. There was no discernable indication of the direction his music would eventually take. Then, teamed with first wife Beverly, he released Stormbringer sometime around the spring of 1969. No longer just the next cab on the lot, John Martyn was finding his particular niche, if largely on the basis of just three songs: “John The Baptist“, which wouldn’t have been out of place on the Band’s first album, “The Ocean“, sung by Beverly but with a fantastic orchestral arrangement, and, especially, “Would You Believe Me?”. It laid down the marker for Martyn’s future sound and style, his first, tentative use of the Echoplex unit that would help shape his music. Even more so, “Would You Believe Me?” had a wonderfully laid back, languid vocal that prefaced the slurred, jazzy phrasing to come. This was music to deepen or lift the depression.

Within a couple of years, John Martyn released Bless The Weather, even more heartfelt, while the presence of Danny Thompson from Pentangle (who’d become a regular accomplice and accompanist) and Fairport’s Richard Thompson on the record confirmed is standing. Bless the Weather achieved the impossible. Here was an album comparable to anything by any of the great American singer songwriters, more so, he was our very own Tim Buckley, embracing undulating folk and gently improvised jazz. John Martyn had become a truly singular artist whose songs simply tugged veraciously at the heart. Was there ever a song as unswervingly tender and romantic as “Head And Heart” or as heartbreakingly, straightforward as “Bless The Weather?”: “Bless the weather that brought us together/curse the storm that takes you away.”

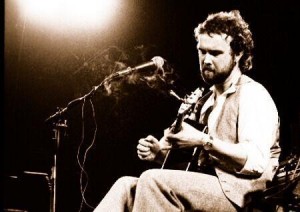

By now, I’d seen John Martyn play live for the first of many times. One of the few redeeming things about being stuck in an oppressive Midlands University at the tail end of the sixties was the extensive concert and club circuit that took in Leicester, Nottingham and Birmingham. You had the opportunity to see everyone worth seeing in that wilfully rich era. Now I was ready for the full experience: John Martyn at Queens Hall in Leicester, looking as unkempt and boyish as on his album sleeves, tousled hair but a with few day’s stubble that smacked of life-lived not a fashion statement. He sat mid-stage, huddled over an acoustic guitar, babbling between songs. There was nothing precious or arty about John Martyn, but his songs were performed with breathtaking ease and passion, then, pow, he’d unleash waves of reverberating guitars on “I’d Rather Be The Devil” or “Glistening Glyndebourne“. How could one man with a mere acoustic guitar generate such a wild torrent of sound that filled the entire auditorium?

It was quite something to see John Martyn in those days – there was a warmth and sensitivity in his vocal delivery combined with a sense of awe about his playing. He’d soon be introducing newer songs that inhabited his most realised work, the astonishing Solid Air and somewhat neglected follow up Inside Out – songs that will live on forever like “Solid Air“, written for Nick Drake, “May You Never“, “Go Down Easy“, “Don‘t Want To Know“, “Make No Mistake” and “So Much In Love With You“.

At the end of eighties, he left Island Records on another high, a final tour de force of bare emotion, Grace & Danger, the one produced by Phil Collins. Around this time, my enthusiasm for John Martyn cooled off aside from returning to those classic albums he made between 1969 and 1973 when the mood took me. I guess I thought I’d somehow moved on whereas he now represented an era that was long gone, usurped by a culturally opposing eighties aesthetic. As decades go, the eighties was kinder to John Martyn than many of his peers. The likes of Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, Davey Graham, Fairport and the Incredible String Band now found themselves out of fashion and, usually, out of a meaningful deal. Not so John Martyn, who switched labels to another major, WEA, before returning home to Island but the emotional edge of his songs was too often softened by bland instrumentation and modern production values. Come the mid-nineties, a new inquisitiveness about the musical past and ‘the catalogue revolution‘ revived many a career. None more so than John Martyn’s, although in his case, as much for his undiminished hard-living-hard-drinking reputation, as for the endiring music he‘d made. In recent years, he’s won all the Awards, if not reaping the financial rewards of his success. In January 2009, amidst the plethora of Team GB athletes, he was even awarded the OBE, responding with typical irreverence: “I’ve been gonged!”

Now, with the news of John Martyn’s death last week, barely a month after one of his first heroes, Davey Graham, the hell-raising folkie has become an endangered species. Martyn had been warned to ‘quit drinking or die’ twenty years ago but in a recent interview explained why he never paid heed: “If I could control myself more, I think the music would be much less interesting. I’d probably be a great deal richer but I’d have had far less fun and I’d be making really dull music.” There is always something seemingly indestructible about larger than life figures like John Martyn. None of us is invincible, of course, though the music John Martyn made will never be destroyed. We’ll definitely not seen his like again.

MICK HOUGHTON