By Jonathan Newdick

We walk on the uneven pavement of the ring road: self-conscious ice rink and Carpets-2-go, bright orange against the blue October sky. Orange balloons tied to the lamp post as if Carpets-2-go is having a party. But it’s deserted. ‘free underlay free fitting kit’ shout the posters as the customer advisers stand about wishing they were at the ice rink. Times are tough at Carpets-2-go but no-one is coming to the party.

Playing chicken with the buses and the bikes and with the unfamiliar lights sequence by the railway station and we turn down the iron-railed stone steps to the start of the canal. Dark and gloomy under the trees. Damp, forgotten, dismal. But people live here, on narrow boats that once carried coal from the west midlands to London via Oxford and the Thames. The opening of the Grand Union in 1805 put paid to most of that and this canal never really recovered. Here, in the city, it seems unrecovered still, but the coal remains – ‘Phurnacite’ in plastic bags on the roofs of the boats . . .

‘Between the hours of 19.30 on Saturday September the 6th and 16.00 hours on Sunday 7th someone trespassed on to this boat and stole a sack of coal. If you have any information . . .’

This path is hardly a towpath, passing uneasily as it does between the sludge-green canal and the river which is really no less sombre but at least it is moving. And within it there is movement too: its surface constantly, silently, ringed by little fishes, silvery things, bleak perhaps. There are fish in the canal too, but deeper, slower, and as green as the water. Small roach, I suppose, drifting aimlessly and barely visible among its dim, weedless clouds. They exist here, that’s all, and without the will to move to cleaner water.

We, however, do have that will and we follow the concrete towpath past the new housing, the urban moorhens and the mallards, one with a broken and bloodied wing. Something apparently amiss with a foot too, for she swims only in pathetic circles. More iron railings and more converted narrow-boats. They occur in clusters of six or eight or so, then there is half a mile of clear water before you see some more, like villages on a long highway. And with them, always, the junk. I suppose there’s not much storage space on a boat designed to carry freight through narrow locks – only the roof really. Grow-bags with spent tomato plants, more Phurnacite in yellow plastic, bicycles and bits of other bicycles, stacks of bricks, logs. Children’s toys, injection-moulded, yellow, pink and blue. And when the roof is overwhelmed it all continues on the other side of the towpath and under the hedge, among the brambles and the bryony.

The willows are shedding their leaves. Long, yellowish, elongate and pointed so that on the water they look like so many dead fish. And in a plastic sleeve pinned to one of the willows a copy of Jericho Matters, the parish magazine of St. Barnabus’ Church, with its Italianate campanile away in the distance.

Isis Lock. On the left the frequent and noisy trains from Leamington-Spa and Didcot and somewhere high above an unseen buzzard calling like an abandoned kitten. On the right the canal begins to be quieter now, more rural and with fewer houseboats although they will re-appear from time to time.

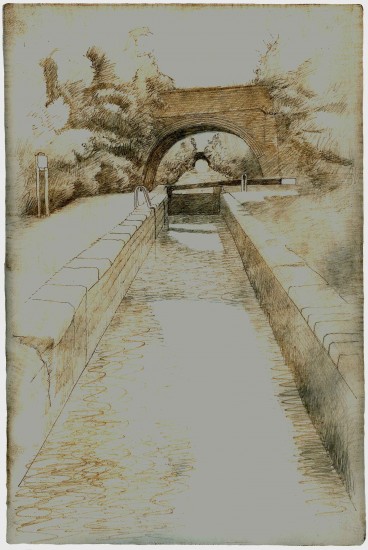

This canal was built on the cheap – narrow locks with single gates and simple lift-bridges made of wood. So simple, indeed that they are almost perfect in their design functionality. Part of the penny-pinching involved incorporating a stretch of the River Cherwell which caused difficulties in regulating the water level in the canal. This, though, has become part of its charm. Each of its locks incorporates a little weir, a bypass channel and a gully to send excess water around it. There are some very nice stone arches now mossed, weedy and green. John Constable would have liked them and the sound of the water through them.

From the north, ahead of us, the distant pounding of a pile-driver. Construction somewhere, or destruction.

All the bridges are numbered . No. 242 is good. Cast iron plates set into the brickwork, numerals serifed and flamboyant, still proud, though grimy now, cobwebbed and rusting. Soft red brickwork with hard grey engineering bricks for the quoins and copings. Ivy-leaved toadflax finds a root-hold in the soft mortar.

On the other side a narrow-boat, bright red paint with black and white lettering: baseplate. miss scarlett & the rooster. I like the sound of this Miss Scarlett but she’s on the other side and I’m over here. Probably just as well – there’ll be an innocent explanation and somehow I don’t want there to be.

private fishing j.r.h.a.c.

Beyond Miss Scarlett, overgrown allotments. Someone is raking his patch – you can hear the rake clicking the stones. A tangle of Michaelmas daisies and the drooping heavy heads of sunflowers. Old canes with the remains of seed packets still threaded on to them.

Below the far bank, the stem of a reedmace shudders and sends a tiny ripple across the water. Down on the mud a silver eel, as thick and smooth as a child’s arm, with a distant memory of a far-away sea, and of birth, and of death.

And here, where you’d expect to see a mildewed moped among the nettles, is a shining new Ducati, racy and red. To misquote Holden Caulfield: ‘ . . . one of those little Italian jobs that can do around two hundred miles an hour.’ Abandoned and on the towpath, its rear tyre flat. A foot-pump on its side on the gravel.

The beat of the pile-driver grows louder and cannot now be drowned by the express train on the left. Wolvercote Green. Between the tracks and the towpath a steel fence with a locked gate carrying a blue and white notice:

network rail. stop check: safety helmet. safety boots. hi-vis clothing. work plan. your location

and we wonder whatever happened to common sense.

As well as the bridges, the locks are all numbered too. Wolvercote Lock (No. 45) is a real gem of vernacular architecture. Green water sliding on to the weir and down through a channel overgrown with hemlock and nettles that could be on its way to the Amazon, before disappearing under a stone arch and re-appearing through another arch, beautifully constructed in the lock wall. Engineering and building on a human scale.

A low growl above and a RAF C-17 transport, landing gear down, points towards Brize Norton. One more coffin with a union flag as a shroud returning from Afghanistan? It doesn’t do to think about it and as the drone of those four jet engines fades behind the trees I return to this lovely stonework. It’s easy to romanticise and equally easy to forget that then it wasn’t Afghanistan, but they died here too, the young men. ‘. . . all the work on it stopped, and I dare say 2000 men were thrown out of employ in one day. They were all starving the heap of them, or next door to it . . . I sold all of my things, shovel and grafting tool and all, to have a meal of food . . . Ever since I was nine years old I’ve got my own living, but now I’m dead beat though I’m only twenty-eight next August.’ (Henry Mayhew, London Labour and London Poor, 1851-61, here writing of the railway navvies, though life was much the same for the builders of the canals).

towpath closed under viaduct access for canal users only please use bridle way

This large, unpunctuated red and white sign with an arrow pointing to the right bars the way. To the left, between the railway and the canal, a yard. Three caravans, no end of galvanised iron entangled among elder trees, motor tyres, gas bottles and milk crates, planks of wood, nettles, a car jack, trailers and a horse box. ‘Private’ it says and the two dogs, a white Jack Russell, gnawing on something bigger than itself, and a handy looking beast, black and formidable, although both chained, would suggest the sign means what it says. This is not a temporary encampment. Someone has lived here for a long time and I’ll bet that Oxfordshire County Council will have it all removed if ever they find a way. But it looks like a sort of paradise to me and it helps to give balance to an ill-balanced and far too tidy countryside.

Nevertheless we do as the unpunctuated sign says and turn right and away from this little oasis. Our detour reveals the source of the beat of the pile-driver. It is in fact a great pneumatic drill fixed half-way up a mobile crane and it is bashing chunks out of a reinforced concrete flyover. Part of the main road high on pillars above the canal. It’s not that old but it’s coming down and a replacement runs alongside it – Fowler Welch Coolchain and Norbert Dentressangle sweeping unheard above us through the rising dust. As well as the pneumatic drill there is a great jaw, or vice, mounted at the end of a high yellow jib and which grasps the concrete girder which the other device is bashing. Dentistry on a massive scale. Together these two are reminiscent of the mechanical dragon from Dr. No which so frightened Ursula Andress. Like Ursula, although all this is strangely compelling, we have no real wish to be anywhere near it and we regain the towpath as soon as we are able.

With the rhythmic bashing far behind us now we walk on towards Kidlington. Drilling winter wheat beyond the hawthorns, clouds of dust after a dry summer. Ahead of us Duke’s Lock, the white painted cottage with its shallow gothic window heads idyllically reflected in the canal with breezy willows behind. When you get closer you find it is rather shabby, but none the worse for that and anyway, the brick, arched bridge over the spur to the Thames and the lock itself seem to be in good repair. There’s a narrow-boat coming in to the lock. It’s a cabinet maker and his wife, Sue, with their two border collies. They are from Southampton and are enjoying the last day of their holiday. They’ve had a good week. The weather’s been lovely.

Ahead of us is Kidlington. Bungalows and the chimes of Mr. Softee greet us. According to John Piper writing on Kidlington in 1938, you could find here the ‘Worst Oxfordshire example of building atrocities’, (Oxon: the Shell Guide to Oxfordshire). We don’t stay to disprove him but catch the bus back to Oxford, to a draught Guinness and a sandwich.

Jonathan Newdick is an artist and writer. To see more of his work go to www.jonathannewdick.co.uk