Roland S. Howard, 24 October 1959 – 30 December 2009. Remembered by James Oldham.

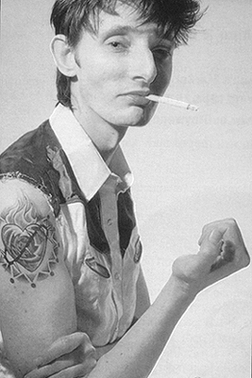

One of the great things about Rowland S Howard is that he looked how he sounded when he played guitar. His face – a cigarette permanently slung at 45 degrees from his lips – had an angular femininity, a waifish aggression that hinted at beauty, but that God had chosen to top off with a boxer’s nose. And that’s how it was when he played, his guitar vibrating out strikingly light, sinewy arabesques interspersed with jolts of violent, shaking feedback.

Howard had arrived at this signature squall in late ’70s Melbourne by channelling his first loves – the music of the Shangri Las and Lee Hazlewood, as well as the obligatory Delta blues – through the intoxicating novelty of punk. By doing so, he arrived at a sound that to many ears sounded harsh and alienating. That, though, was the point. By setting his amp so that there was no bass and no middle only maximum treble drenched in reverb, he was looking for confrontation. And by hooking up with a young Nick Cave, that’s exactly what he found.

Howard went through many bands and incarnations while he was alive, but it’s his work with Cave that he’ll chiefly be remembered for. Originally they came together as equals in the Boys Next Door, a slightly schlocky Australian punk group, deeply indebted to The Saints and Radio Birdman, who later mutated into The Birthday Party. Indeed their most famous song ‘Shivers’ (it took on a life of its own after appearing on the soundtrack to cult film Dogs In Space) was entirely penned by Howard right down to its gauche, existential lyrics (“I’ve been contemplating suide/But it doesn’t really suit my style/So I think I’ll just act bored instead”). Typically, despite it being his most famous song, he hated it – curtly remarking just before his death, “I don’t like to think about it”.

It’s when the band subsequently relocated to London and became The Birthday Party though that Howard’s guitar playing found its ultimate setting. Cave’s increasingly Biblically-brutal missives found the perfect accompaniment in his choatic meshing of blues and punk; a kind of coughing, TB-ridden rattle that defined the band every bit as much as the lyrics. It should also be remembered that Howard was still writing, contributing a handful of key tracks – notably the fury and mayhem of ‘Blast Off’ and ‘Bully Bones’, as well as the snaking ‘Dim Locator’ (perhaps the apogee of Howard’s guitar sound).

The band split in 1983, having moved once again, this time to Berlin. For the next two decades, Howard didn’t deviate far from the blueprint he’d scrawled out as a young man. Although there was much to admire in his subsequent work, first with Crime & The City Solution (the debut EP ‘The Dangling Man’ was a triumph, as was the subsequent ‘Just South Of Heaven’ LP) and then later with These Immortal Souls where he took on lead vocals, there was a feeling that in some ways they were an echo of that startling initial blitzkrieg.

It was actually in the last few years of his life that Howard enjoyed something approaching a creative rebirth. The Horrors publically admitted an allegiance to him (more so than Nick Cave), while his production work with the deeply unsettling Australian drone-rockers HTRK was astonishingly eerie and iconoclastic. Finally, just before his death he completed his second solo record ‘Pop Crimes’. Arguably, his definitive post-Birthday Party statement, it combines the Lee’n’Nancy drama of ‘(I Know) A Girl Called Jonny’ with such utterly desolate and unnerving moments such as his cover of Talk Talk’s ‘Life’s What You Make It’ (“Don’t you just hate it?”). And there on the cover, despite being gripped by rapidly advancing liver cancer, Howard’s almost unchanged face stares balefully out of you. Right to the end, he still looked like he sounded.