by Ben Myers.

It took Channels 4’s retrospective in late 2008 to introduce me to the cinematic and photographic works of Newcastle’s Amber Film Collective. There were two surprises. Firstly, their films are amongst some of the best s I have ever seen, works of social value that are up there with anything by Mike Leigh, Ken Loach, Shane Meadows Terence Davis and Don McCullin. Secondly – and on a personal level – Amber have existed on my north-east doorstep for longer than I have even been alive, and yet I had never even heard of them. Shame on me.

Which begs the question: why aren’t the Amber films – works which, through a combination of documentary and drama, chart the changing aspects of working class life in the north-east (yet crucially always with a universal appeal) – more widely heralded as some of the most important post-war works ever committed to celluloid?

I suspect this questions warrants a response far lengthier piece than this piece can offer. But Caught By The River readers may be specifically interested in three Amber films that could be viewed as a triumvirate of works concerning the death of three industries. Seacoal (1985), In Fading Light (1989) and Eden Valley (1994) dramatise the lives of coal collectors on a Northumberland beach, the sea fishing community of North Shields and the harness horse racing word of rural Durham respectively. There are back stories and sub-plots to each, but ultimately the films are embedded in worlds that economic circumstances and changing political regimes have now squeezed out of existence.

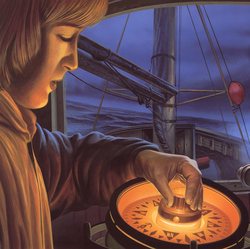

Watching the trawlers and fish gutting factories in ‘In Fading Light’ one is reminded of Robert J. Flaherty recently re-visited 1934 film Man Of Aran were it filtered through ‘Auf Wiedersehen, Pet’, and left questioning the many pro’s and con’s of post-industrial progress. Such big issues sit at the heart of the Amber films, their main strength seemingly an ability to work from within the heart of such communities. Years before Shane Meadows was casting unknowns with little acting experience, Amber were employing the likes of Geordie musician Ray Stubbs and the recently-departed Brian Hogg, two local leading men who turned in performances that are unquestionably believable (Robson Green got his first acting job for Amber too). In the case of ‘In Fading Light’, Amber and their actors bought a fishing boat and took to the North Sea in force eight gales for days at a time, nearly losing members to the sea along the way. All in the quest for authenticity.

Celebrating their 40th anniversary this year, the collective also run the Side gallery and cinema nestled in the shadows of the Tyne Bridge while continuing to stick to their socialist principals of focusing on the marginalised subjects that bigger budgeted films would shy away from. They also helped save many of the buildings at the now-world famous Quayside from demolition down, thereby casually placing themselves at the centre of one of the great British civic regenerations of modern times. In years to come I suspect it will be Amber’s films that people will be watching for an insight in the dying days of a post-industrial / pre-digital world. Amber funding remains limited. Interested parties can always contribute by buying some of their work here.