Frank Cottrell Boyce on ‘Pollard’ by Laura Beatty

I was writing a book about a child who gets fed up of life at home and decides to go and live wild in the local woods. To get myself in the mood, I read a few survival books, then Children of the New Forest, then My Side of the Mountain and then Jeff sent me a copy Pollard by Laura Beatty. It was so good that I had to junk my book and started looking for a new idea. I don’t know if it’s possible for a writer to pay a bigger compliment than that.

Pollard tells the story of a teenager – Anne – who walks out on her chaotic family, follows a fox into the local woods and settles there. Little by little she learns how to survive, weathers a Winter, and becomes part of the landscape herself. But this isn’t some transcendent escape into the wilderness – it’s not Gavin Maxwell strolling off into Knoydart with his pet otter loping alongside him. The magic of Pollard is that the landscape is so recognisable and ordinary. The woods have colour coded walks and dog-friendly areas. The frail threads of friendship that connect Anne to the rest of humanity are with the park ranger, the cafe owner, a local activist and a dysfunctional boy who introduces himself as Peter Parker. Anne is ordinary too. She’s just another disaffected teenager, and so is Peter Parker and for a while in the middle, I thought their story would resolve itself into just another headline about marginalised people murdering each other – Edlington was in the news when I was reading it. I don’t want to spoil it for you so I won’t go into detail but it doesn’t pan out like that. Yes Anne is a homeless teenager but she’s not a sociological specimen. She’s a human being with a soul, in a book that’s shot through with real poetry, where even the trees have their say, telling their own story with their own extended sense of the passage of time. I read the book in tandem with a handsome reissue of Gavin Maxwell’s Ring of Bright Water and the two stories couldn’t be more different. Maxwell goes off to Knoydart with his otter because one of his friends just happens to have a house to spare. One of Maxwell’s friends was Uilleamena MacCrae, proprietor of the Lochailort Inn of whom he says, “it was perhaps a measure of her personality that she was able to owe her greengrocer £3000!” This is not quite the same as living rough in a shelter in your local woodland. But both Beatty and Maxwell have the same blessed gift – a poet’s eye for detail that makes you want to go and try it yourself. There is a moment in Ring of Bright Water where he describes the sensation of showering in a waterfall and how the sheer pressure of the water prevents you from feeling cold, until you step out of it. It’s a meticulous piece of writing, recording every sensation in a kind of ecstasy of detail. Next time I passed a waterfall I just had to have a go (it was in Ingleton and it was bloody freezing). Beatty has a similar gift. In the woods she says, “rain is first sound and wet second”. You can feel the weight of time that Beatty has put into her observations of how the fox gets through the dreary Winter one day at a time. Describing the odd economy of favours and information that governs Anne’s relationship with the Ranger, I found myself thinking, that might work, maybe I could give it a try. I’ve seldom read a book that brings home what it feels like to be cold, hungry and hopeful so vividly. It’s as rich, warm and real as a deep, fecund loam.

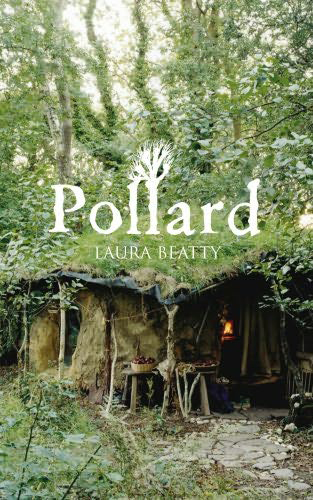

Pollard is published by Chatto & Windus. The cover image used to illustrate this piece is from the hardback edition. We have paperback copies on sale in our shop.