Book review by Bill Black.

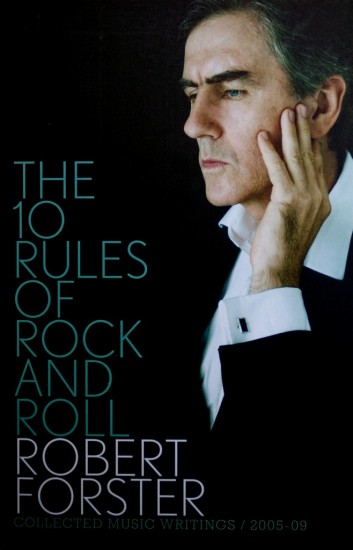

Given that the former Go Between – and half of one of the greatest songwriting alliances ever – has chosen to take as the title of his first collection of rock writing his own Ten Rules of Rock And Roll, it seems only fair that I should repeat them here:

1. Never follow an artist who describes his or her work as ‘dark’.

2. The second-last song on every album is the weakest.

3. Great bands tend to look alike.

4. Being a rock star is a 24-hour-a-day job.

5. The band with the most tattoos has the worst songs.

6. No band does anything new on stage after the first 20 minutes.

7. The guitarist who changes guitars on stage after every third number is showing you his guitar collection.

8. Every great artist hides behind their manager.

9. Great bands don’t have members making solo albums.

10. The three-piece band is the purest form of rock and roll expression.

Interestingly, with the possible, albeit tangential, exception of Number 4, he makes no mention of the Rock and Roll Rule that states “Bands featuring music journalists in their ranks are to not to be trusted”. This old chestnut is not a hard and fast one – think of the still relevant contributions made by Chrissie Hynde or Lenny Kaye, Nick Kent or Mick Farren. But it holds sufficiently well that I’m surprised it doesn’t make it to at least sub-clause status here.

And what does any of this have to do with the price of peonies? Well, I could say that with this book Robert Forster has strayed on to my patch.

I was a jobbing music journalist-slash-aspiring musician when I first came across the Go Betweens, in their early, ‘classic’ line up. It was the summer of 1981 and they were playing the Rock Garden in London’s Covent Garden. Grant McLennan – the other half of the Go Betweens’ formidable songwriting arsenal – was still on bass (a Fender Mustang as I recall, with a fetching stripe over its haunch) and Lindy Morrison was on drums. At the time, Rough Trade Records was readying the UK release their first album, “Send Me A Lullaby” – recorded that year in their native Australia with the same, stripped down, Rule 10-obeying line-up.

However, it was the following year’s “Before Hollywood”, recorded in the UK for Rough Trade, that sealed the deal for me. I bought it, as I recall, on the same day and at the same time as Aztec Camera’s “High Land, Hard Rain” – a financial double-whammy my paltry freelance earnings struggled to cover.

You know where I’m going with this: The Go Betweens’ music became a beacon of sorts, my guiding light through the dark times that followed my slash-stroke-hyphened double-life. Freelance music writer by day, devoted bassist-cum-aspiring songwriter by night. A trip I took, increasingly, in the one-step-removed company of the band themselves, by now virtually based in the UK.

By which I mean I attended their gigs, interviewing them whenever and for whomever I could – starting with a lost-to-the-memory encounter for Noise! a short-lived rival to Smash Hits’ all-conquering matey ethos whose celebrations of early-’80s “new pop” was carefully underwritten by a fair chunk of new-town heavy metal and PosiPunk, courtesy of its publishers, the people behind Sounds.

Which is where, following the unlamented demise of Noise!, I ended up. And where I most trepidatiously combined the job of writing about music with maintaining my indie credentials as a member of The Loft, freshly signed by Alan McGee to his newly-launched Creation records. If the bands I interviewed felt I was somehow taking them on at their own game, they were kind enough not to show it (or rather they possibly found the threat to be so insubstantial as to require no further comment).

I thrilled at the proximity of it all. But I might have more usefully looked closer to home for the fault lines that run through any aspirant musical outfit with not one but two music journalists in its midst. The Loft split up in 1988, leaving me to reconvene around two separate line ups of The Wishing Stones, recording two singles for Head Records and a posthumously released album featuring two further singles for Sub Aqua, both labels set up and run by CBTR’s chief architect, Jeff Barrett.

It was as songwriter and frontman of The Wishing Stones – and in cahoots with Jeff – that I probably spent the most time in the company of The Go Betweens – their ranks now swollen to an un-Rule-y four members with the addition of Robert Vickers on bass (they would ultimately make five, when Amanda Brown joined them on strings, woodwind and backing vocals). We definitely played a few gigs in support. On one occasion, I remember, only the swift application of their rider’s entire allocation of vodka saved me from a visit to the A&E department after I sliced my foot open on a broken pint glass (thank you Lindy).

In time, my band broke up and I returned to writing full time. The Go Betweens continued, dividing their time between hemispheres, experimenting with the kind of augmented simplicity that defined their best recordings, prospering intermittently thanks to the heartfelt support of more commercially celebrated artists, before bowing out for the first time (there would be a reformation) with 1988’s “16 Lovers Lane” (the one with the sublime “Streets Of My Town”). Our paths never properly crossed again, although I do remember a room above a pub somewhere in the noughties when Robert and Grant performed their own material under their own names, but together. The Go Betweens in all but name, then.

And now this: a collection of Robert Forster’s music writing (“rock journalism” doesn’t really do it justice, doesn’t account for the choices, much less the approach – of which more later). His introduction is dignified rather than sheepish, but he asks much the same questions I did when I was made aware of this work: why, and why should it be any good? Well to answer the first, Robert’s intro kindly reminded me of the one example of his journalism I’d seen prior to these pieces (all commissioned by Australian magazine The Monthly) – an article on hair care for Manchester magazine Debris. I remember it well: Robert advised limiting the use of shampoo (no hair is that dirty, he argued, and, anyway, brands only show a mass of soapy lather to maximise sales) in favour of going in hard with the conditioner. (He also suggested greying hair looked best when dyed grey all over. It was daring stuff, particularly as the then-emergent Stourbridge scene was articulating a ludicrous amount of jet-black lockery.)

The Ten Rules Of Rock And Roll doesn’t re-hash his hair-care advice. Instead, it collects Forster’s reviews, criticism, meditations and, appearing here together for the first time, the two eulogies he prepared following the death of his long-time musical partner and oldest friend Grant McLennan, who died from a heart attack in 2006, aged 48.

As Forster describes it, he was given a fairly wide brief when first invited to pen a regular column for The Monthly. Thus some of the reviews are pegged to important releases, big game names and marquee artefacts. Others celebrate the kind of songwriting – always literate, occasionally popular, generally evergreen – that is of particular interest to Forster – performers whose work he has admired from afar or been lost in for years. Chief among the latter is Bob Dylan, for whom he is avowedly no apologist. Indeed, Dylan’s much-touted triptych of recordings, starting with “Time Out Of Mind” and ending with “Modern Times” gets an increasingly tepid response from Forster. As he says himself, “In so much of his best work, especially in the ’60s and ’70s, [Dylan] had the ability to top one great line with another, then top it with another, a dazzling display of brilliance that left listeners and his songwriter contemporaries stunned.” Certainly he finds examples on these records, perhaps just not the same excitement at discovering them.

Interestingly, what I recall of Forster’s mordant, wit is largely absent in these writings. Instead, the reader’s bowled over by its foster sibling, diligence. Throughout, Forster’s tone is collegiate, engaged yet respectful; not so much ‘I’m with the band’ as “I share in some ways this particular group’s ideals and I applaud the journey they’re about to make.” Moreover, he’s often less interested in the art that’s being made, than the manner in which its creation has been approached. And if that sounds overtly dry, overly considered, then so be it, because Forster is meticulous in playing the ball, not the man.

Meaning: too often, critics tend to review an artist’s last album, rather than spend their time listening to their new one (and if we were to anoint that the eleventh Rock and Roll Rule, I’m duty-bound to attribute it to its author, David Hepworth). But Forster is careful, clinical even, in simply listening to what, in another life, at another time, in another’s hands, would be said to be “in the grooves”. Like the rest of us, he’s a stickler for a resonant line, a well-turned rhyme. But he’s also tuned in to the assiduous deployment of studio techniques – just so long as it’s in service to the song – and he boasts that rarely explored feel for the pacing of a great record, mostly lost in the long flat expanse of a CD’s storage capacity these days, but a skill nonetheless (see: Rule 2).

Still, when all is said and done, I suppose I was a critic who fancied his chances as a rock star (or at the very least someone who could pen an evergreen, if perennially overlooked, tune). So I will play the man and not the ball, and confess that perhaps my greatest pleasure in reading Robert Forster’s writings on music here for the first time, is the sheer incidence of shared feeling: whether it’s for the Rough Trade shop, Guy Clark’s “Old No. 1” or White Bicycles: Making Music In The Sixties, Joe Boyd’s elegant summary of why the late Sixties/early Seventies really were different for lovers – and makers – of good music.

True, some of it seems so familiar it hardly merits the repetition inherent in some of these pieces; but then you come across Nick Drake’s “hushed, dark-wood folk” or “the almost medicated impassiveness” of Nana Mouskouri, and you realise concision harnessed to a real understanding of what makes great art, is no less an art itself.

Forster’s on shakier ground when it comes to live reviews. Stripped of its studio vernacular, the language here doesn’t work so well, bands are “rehearsed with in an inch of their lives” or restrained sufficiently to allow a singer’s “voice to soar”. But his twin tributes to Grant suffer no such comparison.

From the outset, I felt had more in common musically with Grant. Here he’s remembered as implausibly well-read, a man with no use for many of the trappings of modern life. I suppose I responded to the combination of the two: his love of blue collar rhythms run through with the Romantics. But I found him the harder man to know. Whereas Robert’s approach, whilst not wildly dissimilar (girl groups; grainy rock) was more overtly cerebral, his melodies correspondingly more ‘flinty’, yet belied what to me seemed the warmer character.

It’s certainly been a pleasure to spend time in his unjaundiced company again.

A word about the author

Bill Black was a freelance writer variously employed by Noise!, Sounds, and City Limits who took his pen name from Elvis Presley’s first bass player. Following a move to the New Musical Express in 1985 – and after an uncomfortable interview with The Sid Presley Experience (during which the singer, Peter Coyne, darkly refused to believe anyone would be stupid enough to appropriate the name of one of his heroes) – he took on the pseudonym, Bobby Surf, purloined from the anti-hero of Nik Cohn’s “I Am Still The Greatest Says Johnny Angelo”, only abandoning it when he joined the paper’s staff in 1988, at which point he reverted to his real name, Bill Prince. He went on to become Assistant Editor of Q. He is currently the Deputy Editor of British GQ.