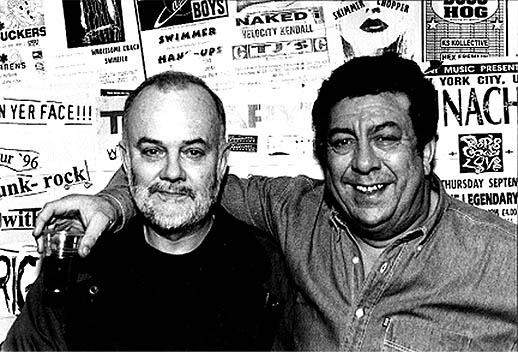

One of the most loved characters in Welsh rock’n’roll history died last weekend. Two locals pay tribute to the man behind the legendary gig venue TJ’s.

Richard King

A few doors down from the Victorian redbrick Art School and a few steps back from the riverfront sounds like a suitably romantic and bohemian location for one of the most innovative, wholehearted and riotous venues in the UK. But this is Newport. The Art School faculty long moved out to the Roman tranquillity of Caerleon, leaving a fading empty shell; and the river is very rarely anything but the texture and colour of steelworks slurry. TJs also neighbours a revolving cast of takeaways, a multi-story car park, a run down cinema and a cenotaph. One of my most vivid memories is standing on the back benches and seeing a goods train pass by on the viaduct opposite, the sun was going down and the first of the three bands was starting their set. TJs and its owner John Sicoro were always street level in every way.

John Sicoro, or Johnny Seico, a bear of a man with a bear sized heart, came ashore from the Merchant Navy in 1971. His premises on Clarence Place were first a steak house then, named after himself and his wife Trilby, TJs Disco. In 1984 in response to the Miner’s strike Simon Phillips of Rockaway Records market stall started hosting benefit gigs. Realising the hunger for live music in the area, Phillips and partner Richard Kendall started Cheap Sweat Fun, a promotions company that would call TJs home from home for the next ten years and beyond. Cheap Sweaty Fun’s booking policy was centred on American punk and underground music; Fugazi, Dinosaur Jr, Shellac, Jesus Lizard, to name a handful, played TJs more than once. As well as for the excitable crowds, the main reason they returned was for John Sicoro. Ebullient, swarthy and avuncular this half-Welsh half-Seychellian gentleman made every band feel comfortable. Assuring them all that for this night, they were to call TJs home. A trained chef he would regularly cook for the bands and made sure the accommodation above the venue was at their disposal. In the late 80s and early 90s club circuit this kind of behaviour was unheard of.

A culture of self-reliance, co-operation and raucousness grew up around TJs. Scores of DIY British bands whose nearest brush with the mainstream was a feature in Sounds or a Peel Session would find themselves time and again in Newport, buoyed by the high spirits and thirst for excitement of TJs after dark. On top of which, Sicoro’s natural charm and fantastic memory made him a born raconteur, never more at home than entertaining visiting bands with tall stories and his bilious laughter.

As well as live music, Sicoro regularly stood on the door or at the bar every Friday and Saturday night enjoying every minute of the TJs club nights. With the decline of steel manufacturing, one of Newport’s main industries was binge drinking. The weekend nights at TJs were among the safest, friendliest and wildest in the area. The annual Christmas party would see Sicoro wading into the mosh pit throwing presents into the air, laughing ecstatically at the mayhem around him.

As the network TJs established turned into a groundswell of local activity the club became recognised as a pioneering seedbed for the likes of Manic Street Preachers, 60ft Dolls, Novocaine, and the Welsh language Punk culture that spawned Super Furry Animals and Gorkys. Sicoro was both proud and bemused, particularly by the fact the local authority, despite the plaudits, never fully understood TJs. The civil servants, even when praising the venue as a Creative Industries Hub, or similar, often managed to erroneously convince themselves it was really a bed of vice.

The last time I spoke to him he talked excitedly about the imminent prospect of part of the Art School returning to the city centre, the memorabilia behind him hanging in the bar a testament to a lifetime of free-spirited generosity. Yes, Kurt Cobain was there in the back corner the night Hole tore through Pretty On The Inside; but when Fugazi were faced with a the prospect of a meagre audience, Sicoro kept the band’s spirits up while Phillips and Kendall stood outside trying to drag people in off the street or make a coin donation for the band’s petrol tank. It was that kind of place.

John Sicoro loved Newport to bursting. And the bands from all over the world, the crowds and all the nights of cheap sweaty fun, loved him – his black curls, loose jumpers, and his mischievous smile – all of him, back.