Tim Dee, author of The Running Sky shares his joys of May.

May is the finest month. On Mayday morning everything is still to come, by June the best of the year is over. Spring opens fully to green life through May’s weeks. Sunlight stretches days earlier and later. The season thickens with birdsong and juiced-up leaves. It is time to make hay.

The month seems too good to be squeezed into thirty-one days. Every May I want to be outside for every minute; every May I dream of making the four weeks last six months, seeking May-in-February in Crete all the way to May-in-July in the Norwegian Lofoten Islands. You could even walk it. Spring, it has been said, moves at four miles an hour northwards. That is about walking pace. Imagine moving through Europe from the Mediterranean to the Arctic Circle with May unfurling all around you; imagine living in the best month for half the year.

This May has been a good one. The frosts and freezes of the winter held things back until sudden southern warmth flushed everything at once. I’ve seen daffodils and bluebells together in flower, tarrying winter ducks surrounded by breeding waders. Hedge blossom came before leaves and stayed like champagne froth that didn’t disappear. Driving on back roads from Cambridge to North Norfolk was like moving through lace underwear. Whitethroats and lesser whitethroats scratched and rattled in relay from the hawthorns and cow-parsley, like burrs snagged in the linen. All that lust for life excites every sense.

On the car CD player, between Sylvia warbler anthems, tracks from High Violet, the new and very fine album by The National. Is there a better current rock band for old guys? ‘Runaway’ is a superb slow baffled song of ecocide and fallen man, and it is perfect for May: ‘There’s no saving anything/Now we’re swallowing the shine of the sun…’

I watched a more benign version of this – all of May’s green comes from the hoisting of the sun – in New England. Mount Auburn cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts is a wonderful place to see spring American warblers on their flights north. The graveyard has mature trees and ponds and forms an oasis in otherwise built-up and built-over greater Boston. It functions for migrant birds as Central Park in New York City does.

Mount Auburn is an oddly secular burial ground. Most of the nineteenth century tombstones detail the names of the dead but not much else. There are not many stone angels. For a few weeks – May, again – the lift-off role, things leaving the earth for the skies, is taken by the few inches of warbler flesh and feather that flit through the cemetery, flycatching from tombstones and singing from the ornamental trees.

I work as a BBC radio producer and had been recording five talks with the genius literary critic Christopher Ricks of Boston University. Coincidentally but appropriately these were on various kinds of pastoral in poetry. Having discussed poems of innocence and experience, the young and the old, town and country, and the rich and the poor, Christopher showed me the way to the cemetery and left me stalking about the graves sorting out the busy fizzing warblers and orioles that seemed to dramatise everything we had been recording. Which was the innocent and which the experienced? The bird no more than a couple of years old following migration routes invisibly woven across centuries and through the vast landscapes of the Americas, or the human idea behind burying a body, erecting heavy stonework over it, and dreaming of an escape for its imagined soul?

The spring warblers are beautiful without exception. Some bring colours into the temperate north they seem to have gathered on their wintering grounds in the tropics. The yellow of the yellow warbler is as scorching as a field of rape. The male Baltimore oriole seems to be on fire. Others are quieter to look at but no less exquisite. A black and white warbler mouses around a trunk like an animated bar code or a dwarf zebra in a tree; an ovenbird turns over leaf mould as if stoking it, its flame-orange crest-stripe kindling the dead leaves of the shaded under-storey into life. They are sun swallows, all of them.

There are panics in May too. I loved the northern parula and the bobolink that the cemetery showed me but by being there I wasn’t somewhere else where May was equally underway. The heady euphoria of the great kick-off sometimes means you feel that it is even greener over the hill, that cuckoos are never calling quite where you are, that if you miss the horse chestnut candles at their prime your year will never light up. My work dictates that I spend some hours each week in acoustically insulated and windowless radio studios. In May these places are like grim floatation tanks, airless sites of sensory deprivation. This year I have tried to compensate by making poetry programmes stuffed with bunches of flowers and heady with haymaking (listen to Poetry Please in June) and by planning a radio play, written by Jonathan Davidson, that will be set (and recorded) in an apple orchard. For this last I have been to see the second genius of my genius month, the quite wonderful Barrie Juniper (read his book The Story of the Apple for enlightenment about the role horseshit played in the arrival of the apple in western Europe and much other essential apple wisdom). I am hoping to persuade Barrie to talk apples in the play as Herne the Hunter or some other dryad might – down from the fruiting boughs themselves (listen to Miss Balcombe’s Orchard on Radio 4 on 18th August to learn if I have been successful).

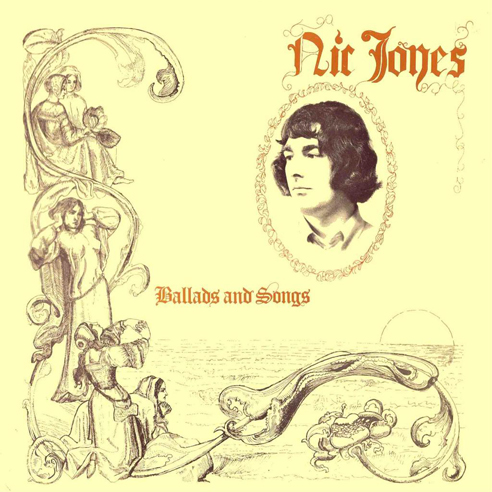

Meanwhile, I also love less complicated versions of pastoral. This month I was thrilled to find at last a CD reissue of Nic Jones’s first record, Ballads and Songs from 1970. I’ve long treasured an increasingly ropey cassette recording of the album that faithfully and hissily copied the scratches of a friend’s vinyl version as well as the nine songs. It was so precious I rationed my listenings.

The CD is wonderful to have, though I find myself expecting the scratches that are not on it. The record contains several performances that put Nic Jones to my (and many) ears right at the top of British folk music. My all time favourite is his version of the ballad of ‘Little Musgrave’. Musgrave is a kind of medieval Mellors (of Lady Chatterley fame). There is something of the virile nature boy about him. He dives into bed with his Lady whilst her Lord is off hunting. In the early – May, I imagine – morning the post-coital lovers stir, woken by the birds. Musgrave tries to get up: ‘Oh, I think I hear the morning cock, I think I hear the jay…away, Musgrave, away…’ But his new lover shushes him back to sexy sleep and the next thing (and almost the last thing) Musgrave knows is that the Lord has come home and stands at the foot of his marriage bed with a sword in his hand. Pay attention to the birds, you might say.

Tim Dee is a BBC radio producer and writer. His memoir of his birdwatching life, The Running Sky, is out in paperback and on sale in our shop priced £8.50.

Tim will be appearing on the Caught by the River stage at Port Eliot Festival on Saturday July 24th as part of Ceri Levy’s Bird Effect session.