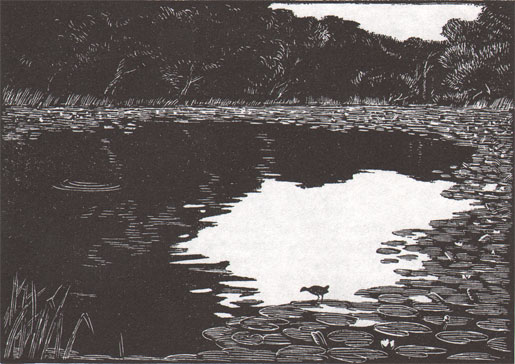

illustration by Denys Watkins-Pitchford. Taken from ‘The Fisherman’s Bedside Book’ by BB.

illustration by Denys Watkins-Pitchford. Taken from ‘The Fisherman’s Bedside Book’ by BB.

The Fishermen. by Chris Yates. A brand new piece of writing, exclusive to Caught by the River.

The woods and fields promised escape and adventure, but the pond had a different appeal. From a distance it often looked dull and lifeless; close to I could see it was in constant slow motion. Even on the calmest day it gently stirred and flexed like a sleeping animal, flinching everytime a duck landed on it, shuddering if someone ran heavily along the banks. A puff of wind would make it ruffle itself playfully, sending ripples chasing one way then the other; but if it was quiet for too long I’d wake it up with a big stone, smashing its surface, creating a bumping circular wave that spread out evenly from bank to bank. I also liked to take my shoes and socks off and thrash the shallow margins into spray and bubbles. Yet, whatever the disruption, the pond would always recompose itself, patiently smoothing out its ripples and settling back into its natural supine state. It was a curious but mostly friendly creature, although there were moments, especially in the late evenings, when I felt it was regarding me with an unfamiliar hungry expression.

It was also in the evenings that the fishermen would often appear. After teatime on weekdays the bankside would usually be deserted until, in ones or twos, on foot or on bicycles, a few local men would arrive with their tackle and quietly prepare to cast. I liked the way they unfussily became part of the bankside, so different from the flapping, chattering weekend picnic parties; and despite being grown-ups, their stillness made them less intimidating than the striding stick-throwing dog walkers. However, despite their apparent seriousness, I soon began to suspect that fishing was simply a quieter version of the games my friends and I played, like the hunting of dragons in the woods. We never caught any dragons, the anglers never caught any fish; but we only had home made bows and arrows while the angler’s toys were far more sophisticated. Firstly they fixed together their delicate rods and shiny reels, then they wove invisible knots with impossibly fine line, attaching colourful floats which by some trick they flicked far out across the water. The game had now properly begun and, with the anglers on their creels and me in the bankside grass, we waited expectantly for something to happen. Poised upright, the anchored floats were the focus of attention – floats made from swan or crow quills with tips painted crimson, amber or lemon yellow, some with black stripes. I loved their appearance, but, being young and witless, did not understand their real purpose. When, having summoned the courage to ask, I was told that a float would vanish if a fish took the bait, everything made sense – for a while; but the longer the floats sat colourfully on the surface the less faith I had in them. Furthermore, I did not truly believe in the existence of fish. In all my explorations I had never seen anything other than water beetles, pond skaters and tadpoles, nor had any of my pals ever mentioned anything more dramatic than a frog. Perhaps, in ages past, fabulous creatures really did inhabit the pond, but now the anglers simply cast their lines in an act of remembrance, just as I kept revisiting a hallowed place on the heath where, long ago, my Uncle Ralph once saw a grass snake.

Yet whether angling was just a nostalgic gesture or a game – a waiting game – or a genuine adventure I never became bored watching it, and, like most children, I could get bored quite easily. On long summer evenings it was easy to sit by the pond until the swallows stopped skimming the surface, the fishermen had faded to silhouettes and the floats had all vanished, but only because of the dark.