by Ben McCormick

Gil Scott-Heron died yesterday. Or was it the day before. I forget. I found out via a rumour on Twitter that was only confirmed the next day. If you’re looking for a eulogy, there are plenty already on the internet that should fulfil your needs. This is a purely personal hats off to someone who’s been a pretty much constant presence on my stereo for the last 20-odd years and whose lyrics, poetry, call it what you will have kicked me up the arse, given me hope or opened my mind to the fact that, maybe, just maybe, I’m not the lowest of the low.

My first introduction to the music was while smoking daft-smelling resin in the 12th-storey flat of the guy who went on to play Cain Dingle in Emmerdale. Cheers, Jeff. I’d been something of an indie Nazi before then, with the occasional leaning towards reggae and half an ear cocked to my step-dad’s jazz collection, but not much prepared me for the onslaught of The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. Astonishing, especially given how much hip hop was being listened to around the world at the time. So that’s where it all began, I thought. But having resolved then and there to seek out more of his stuff, it wasn’t until several years later in a bar in Turkey that I had my second brush with the man’s music. We took control of the hotel bar stereo and someone stuck on a tape just at the start of Whitey On The Moon. I’d never really before experienced what felt at the time like racism, but was suitably impressed any way. Here was a man sneering at the greed and cynicism of the white supremacy and all I could do as a white man was totally agree.

But it was When You Are Who You Are that really did it for me. Pushed me over the edge into barely contained obsession. I was feeling pretty low at the time and trying out all kinds of personas in an effort to be loved. Yet there, writ and sung large, was the key. Needless to say I’ve tried out many more personalities in the intervening years, it being fairly difficult to genuinely be who you are, but it’s a song I’ve always returned to when either trying to pick myself up off the floor or attempting to reassure others.

From that moment, I dug deep into the oeuvre. The dad-like, gravelly voice made up for the loss of my own father a year later. And the words. The stories. The brilliantly documented tales of woe, addiction and defeat. They all helped steer me back to some semblance of normality when things started to go wrong. Here was a presence that would keep me on the straight and narrow no matter how events or emotions were shaping up. And there was hope too. I Think I’ll Call It Morning sounds like a manifesto for the downtrodden and broken trying to fix themselves, while the classic Lady Day and John Coltrane never fails to raise a smile and shore up the resolve.

Then there was The Bottle. As a beer writer, it’s often difficult to admit that you’re sailing dangerously close to borderline alcoholism. No, no, I just like the taste, you’ll claim. The complexity. The craft of fine brewers’ wares. And to some extent, that’s true. But scratch the surface of any writer on booze and there’s a dodgy relationship going on there. Most beer writers I know will regularly pile in much more than’s supposedly healthy, while striving to conceal the appetite for inebriation behind a veneer of research. The Bottle demonstrates the decline most of us are fighting to avoid, mostly with a degree of success admittedly, but not universally. It’s pretty much my go-to song when I feel like I’m losing the fight. A cautionary tale. I believe it’s working so far.

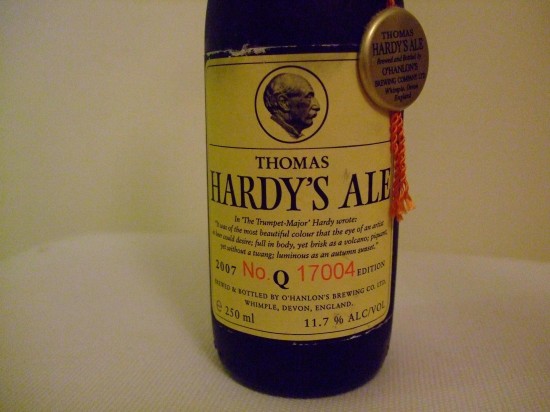

So when I heard about Gil Scott-Heron’s death at the age of 62, it felt like my guardian had gone. And what would be my tribute? I’m almost ashamed to say that it would be the opening of a five-year-old bottle of O’Hanlon’s Thomas Hardy’s Ale that’s been gathering dust since I bought it for a special occasion. I’m not sure special is quite the right word, but it does seem sort of fitting that I’m seeing off a bottle I’ve laid down in honour of someone who’s just been laid to rest and whose work kept me this side of sane for so many years.

And at a frankly preposterous 11.7%, it’s already calling into question my claim to be the right side of the alcoholic divide. It’s stronger than the wine I had last night and considerably older too. There is a part of me that’s uneasy about trying to describe a beer while remembering the recently departed, but it’s what I do and, frankly, much of Gil Scott-Heron’s output made me feel uneasy anyway, so I’ll crow-bar that in by way of justification.

Smells initally like a Belgian Lambic beer, which is both pleasing and dread-inspiring at the same time. Then a whiff of off Marmite strips out the nostril hair and puts paid to any idea this will be a pleasant experience. The colour’s off-putting too. Even when held up to the light, you can’t quite shake the impression of diluted sump oil.

It’s billed as Britain’s strongest ale and the label claims it can be kept for up to 25 years, but I remain to be convinced. That wariness is borne out when I taste it. It’s an horrifically salty assault on the senses. Any complexities I’d hoped had developed over time are wiped out by a shoal of anchovies writhing around in a grit bunker of coarse sodium. Only a few sips in and it’s clear – unlike the beer itself – that it’ll take the kind of dedication usually only found in real drunkards to finish it. I’ve had strong beers before that tip the nod to this kind of thing, but they usually have some kind of saving grace. Not so Thomas Hardy’s Ale, which is almost as impenetrable as The Mayor of Casterbridge is to a callow 16-year-old GCSE student.

But I’ll see it through to the end in some misguided notion of propriety and respect. It’s what Gil would have warned against and, now he’s no longer around, there’s not a lot left to stop me.