Caught by the River contributor Kurt Jackson has a new exhibition at the Lemon Street Gallery in Truro, Cornwall running from now until October 8th.

Press release:

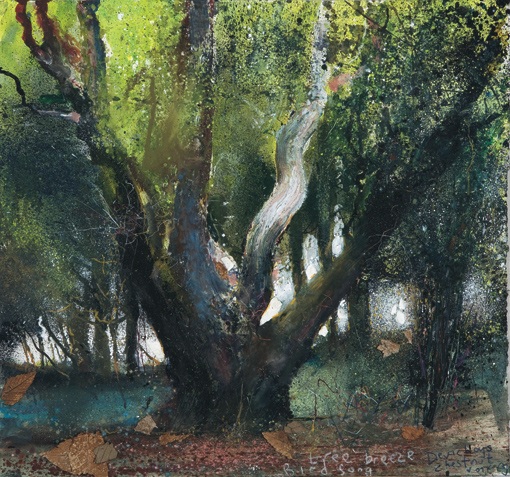

For the last few years Jackson has turned his attention to the tree population of Cornwall. Without the intention of producing an encyclopedic survey of these plants, he has aimed to celebrate and capture particular individuals familiar to him, as well as searching out certain infamous veterans and examples of some of the more characterful and maybe characteristic species.

Although not renowned for its tree cover, Cornwall has evolved a very particular population of trees whose form and distribution has been determined by the nature of the geography and the elements in this part of the world. Jackson has painted and drawn, etched and sculpted the wind-blasted thorns in the west; immersed himself in the depths of boggy willow carr and pristine ancient woodland; and explored the Cornish coasts and inlands for his subjects. This body of work includes the rarest tree in Britain and some of the oldest – trees planted by his family in their orchard, trees in blossom, in fruit, naked in winter. From small intimate studies to large expressive canvases, sketchbooks, sculptures and even a film, Jackson’s body of work is extensive.

To quote nature writer, reviewer and journalist Richard Mabey, “The forest is the great reservoir of life’s diversity; the touchstone by which we can understand our own origins; the generator of oxygen and regulator of climate. But in our psyches, as in painting, it is still an alien and mysterious presence. The forest has become our backdrop. Jackson has questioned this shortsighted, conventional perspective and sought to explore nature in more depth. Even through their modest elevation, Jackson’s woodland pictures challenge the grand, colonial tradition of prospect painting. These are landscapes seen literally from the grass roots. You are in the thicket, enmeshed with greenery. In his many pictures of Cornish lanes and streams the track invariably leads into the wood, not away from it, and you are reminded not so much of any other painter but of the Romantic poet John Clare. The start of his poem The Nightingale’s Nest captures the sense of wonder that draws the viewer into one of Jackson’s wooded landscapes. What is impressive is his painterly translation of the ecology of wild places. The pattern of light and shade, the thick impression of the paint, the sudden detonations of colour and embryonic forms echo the vitality and inventiveness of the natural processes they signify.” Philip Marsden, novelist and travel writer, after spending a day with Jackson, wrote, “A hawthorn stands alone above the spring. We glance at it. Then we find ourselves pausing, drawn in by its isolation and its wind-skewed shape. The more we look at it, the more expressive it becomes. On the branchless upwind side, the bark is polished, sheep-rubbed, the hairs still stuck in it. There is something animal-like in the shape of the boughs. They are not round in section but oblong, as if muscled. From the downwind side streams a great scarf of foliage, the fresh green leaves with the tinge of red still on them, and the white blooms, and the loose-hair strands of new growth waving above them. Jackson ducks in beneath the canopy. ‘Odd … you would expect at least one nest, being the only tree around. There’s none,’ he reflects. He stands back. Yet we remain there, caught by the spell of the tree, by the afternoon light on its boughs, by the twisted course of every branch that leads up from the bole until it is lost in the labyrinth.

“Now Jackson is clutching his sketchbook, scribbling the growth-tangled out across the page, talking, ‘There is an old hawthorn near Morvah. Over the hill there.’ He gestures with his chin to the south. ‘A few years back, I went there every week. I have still got those sketches, fifty-two images of the same tree. It’s like a flipbook or something. The tree is getting its clothes on, its flowers and fruit, then losing them again.’ He steps up and tears off a leaf and rubs it on the page: ‘I met a forestry man the other day.’ He is still drawing. ‘He said that some of these hawthorns have been around for four thousand years. They die back, spring up, die again and come back, but it’s all from the same root. Four thousand years!”

Described in The Financial Times as ‘one of Britain’s most compelling contemporary painters’, Kurt Jackson (b. 1961) has had a distinguished career spanning almost thirty years. An Oxbridge graduate in zoology, Jackson travelled widely before settling in Cornwall in 1984, both to immerse himself in the arts and become more involved in his commitment to the environment. His work embraces an extensive range of materials and techniques, including mixed media, large canvases, relief work, printmaking and sculpture. Jackson’s paintings are set in places that have been travelled to and explored regularly throughout his life and seen through the eyes of an artist with a deep and rich understanding of natural history and ecology, politics and environmental issues, maybe recording a time, a place and a way of life – a geography where past and present co-exist. He is an artist who is fascinated by both the world at his feet and the universe beyond the horizon. A dedication to and celebration of the environment is intrinsic to both his politics and his art, and a holistic involvement with his subjects provides the springboard for formal innovations. Jackson states, “Capturing a fleeting impression doesn’t interest me. In all my paintings the aim is to convey my feelings and sense of awareness in that particular environment.”