By Jasper Winn

I hadn’t counted before just how many years I’ve been coming to this village in Andalusia. But, by going around on my fingers a fair bit, I’ve just worked out that it’s been twenty years since I first walked the sand track into Sanlucar de Guadiana.

Since that first visit the track’s been tarmacked, and there are more cars and less donkeys. There have been two suicides and a murder in recent years. Twice immense floods have washed away boats and pontoons and risen tens of metres up into the villages on both sides of the river. A number of foreigners have moved here, most living self-sufficient lives along the banks of the river. A number of los extranjeros – me included, if only intermittently – are musicians, bringing jazz and acoustic country and rock as counterpoint to the Spanish taste for clattery flamenco and the Portuguese villagers’ love of slow accordion airs. But, really, not that much has changed over the past two decades.

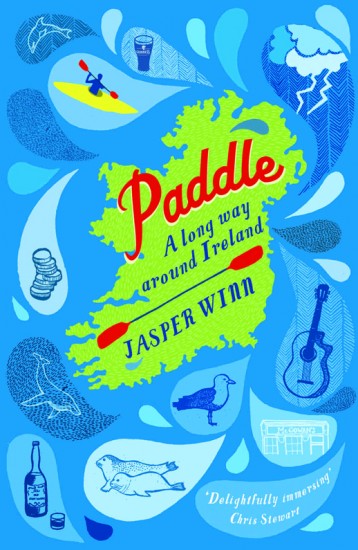

For the past ten years, usually for extended winter periods, I have been lent a friend’s house in the village. It’s where I wrote Paddle; A long way around Ireland, an account of sea-kayaking the thousand miles around Ireland.

There are constants. Yesterday, as always I awoke to a sound like the distant thump of the surf on a beach as Candido, the baker, two doors up the street, started up his kneading machine at four in the morning. It thudded low, slowly and reassuringly through the mud walls of the inter-locked houses. The crabby cockerel next door, almost under my bed, starts crowing then. Often I awake in the night to hear, say, three strokes of the Spanish bells. Two minutes later there will be – just – two answering clangs, softened by distance, from Alcoutim across the river Guadiana.

On the same time-line as Greenwich, Portugal is an hour behind Spain. The river is the border between the two countries and two time zones.

This allows slow time-travel opportunities. By rowing the few hundred yards across the Guadiana – tidal here, some forty miles inland, and tidal still for another thirty miles further until the brackish water hits the rapids at Mertola – I can turn the clock back an hour. So, yesterday I left Spain at ten and was in Portugal for seven minutes past nine, in good time for the market, to buy tiny, plucked quail, ripe plums and fresh vegetables.

After the market I have a couple of coffees, still on the Portuguese side, on the terrace overlooking the river. And then a glass of wine And suddenly – or, really, the opposite of suddenly – I’ve missed the shops back in Spain. Paddle as hard as I might, if it’s 12.59 in Portugal, I’ll arrive back in Sanlucar at 14.05. It’s the downside of time travel. Even Candido will have closed until Monday.

Last night I was out till four in the morning, chatting and drinking and playing music with 50% of the band, The Journeymen, I play harmonica with. Back in Spain I fall asleep in the sun. With the afternoon cooling, in celebration of the autumn that has arrived, I stuff a hammock, sleeping bag, some food and cooking kit into a bag, take my chestnut walking stick and leave the house and the village to walk up-stream. Only a few miles north of here, amongst the steeply rising and falling hills there is a hidden valley that I think of as my outdoor bedroom. A tiny patch of flat ground, a small stream and two wild olive trees just a hammock’s length apart. The last time I slept out here was in late winter on a rare night of frost. Then I’d lain awake, listening to the sonorous booming fog-horn call of an eagle owl.

Now, as I climb the hill there’s a high bubbling sound below me. Bee-eaters. Rising up and down in time with their call on an breeze’s updraught in a ‘V’ of valley running down to the river. And then a dipping, plunging flash of pink and black and white stripes. A hoopoe, Upupa epops. Abubilla in Spanish. All lovely onomatopoeic names which come close to recreating the birds call. But the Arabic hood hood is the closest of all. Close your eyes and say ‘hood hood’ as quickly and as quietly as possible without actually whispering and it’s as if you can hear an actual hoopoe, far away among cork oaks and olives trees.

A hoopoe was my first ‘exotic.’ A bemused, dejected but still flashy little bird walking jerkily like a wind-up tin toy across a sodden field in West Cork, blown to Ireland on an early summer storm. I can still remember, at ten years old, the heart-in-mouth excitement of seeing it and knowing that unlike the dark shapes that ‘might’ have been marsh harriers, or the flash of red that ‘could have been’ a waxwing that the hoopoe absolutely was a hoopoe. Seeing them in Spain still brings me that same thrill.

I’ve always been a bit funny about my interest in birds. I think a lot of people are. You know, reluctant to admit what a source of consolation they are in a pretty messy world; and how just being able to spot and recognise the odd species, and more to watch them going about their lives rather differently from the way we humans go about ours can provide something not far off contentment. But I’m defensive of this. Far more people know about my atheism, dislike of political adherence and how much I drink than know that when I’m feeling a bit glum I will try and get out and watch some bird or other doing something ridiculous, or even uplifting, in the sure knowledge that I’ll then feel better.

Both birds and music – to my mind – are similar. I like both of them in general. But I don’t like – or at least I’m not that gone on – all music, nor, to be honest, all birds. Warblers, for example, are like modern jazz; all pretty much the same, and well to be honest life is brief and there’s many an hour to go before dark. Seagulls, then? Well, they’re modern funk jazz; you think, ‘yeah, i’ve got this,’ i’ve got the beat here,’ one likes the general idea but then it all founders on those first and second year immatures and the extended sax solos, and one realises that seagulls are just modern warblers but bigger and louder.

Birds of prey, on the other hand – my thing, ‘because I like to keep things simple – are rock music. An eagle aloft is Led Zeppelin; not subtle but bloody exciting. A peregrine stooping is a Hendrix solo. The dexterous weaving of a spar’hawk along a hedge is Rory Gallagher extemporising Celtic blues on the fly. Even a kestrel hovering is Peter Frampton.

Meanwhile, on a provocative note, there’s all those people keen to chase down the rarities and storm-blowns and shouldn’t-be-here-at-alls. That’ll be the ornithological equivalent of the Last Night of the Proms, then. A bunch of dafties gathering around something small and fragile – Land of Hope and Glory, say, sheltering in a bush in a garden on the Isle of Wight – and participating it to death.

And then, there’s the exotics. Country music, in my book. An umbrella that covers everything – from the very good to the very bad – from Dolly Parton to the Dartford warbler. From Randy Travis to the magpie? From white-tailed sea eagles to Gram Parsons. And all the odd-balls in the wrong genre or habitat, giving it their best shot. Or at least surviving. Ringo singing Act Naturally? Leonard Cohen and the Buckskin Boys? Bob Dylan – triumphantly – in Nashville? Little Egrets? Red Kite? Fulmars?

Here, in Andalusia, on the Guadiana, the exotics are not the bee-eaters, nor hoopoes, nor egrets but the garden birds of further north scratching a living down in the hot Iberian sun. In the village there are jolly house sparrows up in the eaves and around the café tables. But, still, it always sounds slightly wrong to hear the tschk tschk of a great tit flitting through the hot bushes of Andalusia, especially when one has seen them equally cheerful in the depths of a Swedish winter at 30 below atop six feet of snow. The alarmed skirl of a blackbird and a quick black darting shadow between one bush and another, seems discordant, too. Today it’s the sudden, and unlikely, scattering of long-tailed tits that fly into the tree above my head as I rest for a few minutes in its shade and scurry around, laddering from one twig to another, peeking and pecking under leaf after leaf before, as suddenly, flying off again.

Crossing the hill I leave the sun to walk through the shade following a fire-track round the contour line, and then branching off down into the hidden valley. Within twenty minutes I’ve strung my hammock between the two trees. For the last days it’s been unsettled, with thunder storms and rain and whirling winds, but tonight it looks and feels set fair so I don’t bother to stretch the bivvy-tarp above my bed. There’s clear water in the tiny stream. If I’d known I wouldn’t have lugged a couple of litres from the house along in my pack.

I unfold a Vargo wood stove. A tiny, ounces-light joy that unfolds from flat into a hexagonal cone, like some kind of titanium origami. An open fire would be lovely but the vegetation is tinder dry here and the Vargo is the solution. I became an aficionado of wood-stoves on the trip around Ireland. My fancy mountaineers petrol stove didn’t stand up to the brutal treatment of sea and rain and storm and neglect, and I finished the last five hundred miles cooking on driftwood burnt in a tin-can. Once you’ve done that why would you go back to anything less simple? With wood-stoves there’s always fuel to burn, nothing to go wrong and the real joy of tending a living fire. Playing with fire is still a delight.

I have an Opinel pocket saw to make a pile of four inch, finger-thick dead olive sticks. I stuff the stove with dried grass and twigs before showering sparks into it from a flint and steel. Within a few minutes, just as darkness falls, the flames are lighting up a small circle around me and throwing everything else into shadow. There’s silence again apart from the frogs burping and hiccuping, and crickets and cicadas chirruping. An insistent ‘beeyp,’ beeyp,’ like sonar picking up small random shapes in the dark, starts up; the call of Scops owls. Like the bells of the villages or Candido’s bread-kneader, the Scops owls continue for long periods on and off during the night but are lulling rather than intrusive.

The fire dies down as I eat and there is only a faint glow from the embers. I sit back and swing in the hammock and sip wine from my horn beaker. It’s a present, thoughtfully chosen by someone who knows me well, perhaps too well. After only a few weeks’ of use it’s become a part of my ‘fixtures and fittings.’ I’ve never owned a house. I spend much of each year travelling on horse or by foot, or in kayaks. When I do settle, it’s for a few months of writing, or working wherever there’s a haven. In the past two years alone, I’ve spent half a year in Patagonia working with horses and guiding long distance trips, many winter months in the north of Sweden, and two long stays here in Andalusia, interspersed by a few months house- and dog-sitting in England. And it’s been like that since I was sixteen. So, these small things – a particular knife, my leather notebook case and Waterman ink pen, a pair of Blundstone boots and now this horn cup – are my simple chattels and they are the tangible pleasures that go with the more abstract pleasures of actually doing things, that enhance the physicality of life. Like, now, lying in my hammock under the half moon, and the not-so-bright stars.

There’s a sudden huffing on the far side of the stream. Where I threw the bones from the my lamb chop into the bushes, something is snuffling and smelling them out. I can see nothing more than a shadow, ten yards or so away. I pick up the torch. Aim. Snap it on. Caught in the beam is a large boar. Dark and shag-haired. Eyes reflecting red in the beam. A moment’s stillness, and then he spins round. A single crash of over-run bushes and he’s gone.

The night is measured out by the Scops owls ticking and tocking. A chill breeze starts up and I climb into the bag. Even then I’m not over-warm. There’s no eagle owl tonight. At sunrise I get up and set fire in the stove to boil up water for coffee. I splash my face in the stream amongst the frogs.

Sitting on a rock I sip my coffee from a titanium mug – if I have a fetish, a weakness or an affectation it does seem to be titanium; do people make titanium shoes? Underwear? Hats? I don’t know. But if they do, then obviously I want them.

I hear a sibilant whistle high above, from behind the hill. Repeated. Over and over. Then a cruciform shape, but with the arms bent back at the wrists and its ragged splayed fingers twisting, sweeps in overhead and back out of sight. I’m almost sure it’s a Bonneli’s eagle. A lightly barred tail, a white underside, a russet collar and those wide, bent back wings. I do that birders thing of questioning myself like a severe cross-examining council. Why do I think a Bonneli’s? How about a buzzard – one of several species to chose from? An immature Imperial? Or a booted, or short-toed or spotted eagle?

The same whistling, wheedling bird suddenly swings back over the hill side, this time wings held out straight as it goes with the breeze. And is joined by another, similarly marked and shaped, but silent. I get a long look at both of them. I note stuff. As one should. And it doesn’t help a bit. I still think Bonneli’s eagles. But know I could be wrong. Even very wrong.

Warmed by the sun, coffee-sipping, contemplating the few minutes needed to untie my hammock, disassemble my bedroom and walk the hour of tracks back to the village, I realise that one of the pleasures of life sometimes lies in not knowing something. In being curious and hopeful and interested. But not too knowledgeable. And that makes me happy.

Paddle by Jasper Winn is now on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £7.50