Will Burns pays tribute to his Grandpa, who passed away last week.

Henry Donne, or Roy as he preferred, was not a famous naturalist or fisherman. He was not a prize winning sports writer, or big game hunter. What he was however, was the single biggest influence on three generations of one family’s pronounced and continual relationship with the natural world; the natural world both as a living, vital thing – seen, felt and perhaps most importantly heard, and also the way in which that experience of nature can be subsequently transmuted in words. Roy Donne was a fisherman, hunter, birdwatcher, gardener, and storyteller. And he was my father’s father; brought up in India in a colonial military family that he left forever to join the Royal Indian Navy during the Second World War.

His childhood in India forged a life-long love affair with rivers and birds particularly, but a respect and yearning for the flora and fauna of the sub-continent in general manifested itself in recollections that litter my own memory of childhood; the particular nature of a tiger’s call, the feeding habits of the leopard (expertly assessed upon the untimely death of an aunt’s dog when he was a boy), the differences between African and Indian elephants and all other manner of forest lore, myths, stories and knowledge that he brought to bear on our many walks in the woods of the Chiltern Hills. No big cats out there in the twilight, but tawny owl calls, the diagnostic flight of jays, mistle thrushes and green woodpeckers (he especially loved the undulating flight of these birds, I think), and homely mnemonics to remember the songs of the chaffinch and the yellowhammer seemed to bring equal pleasure, and became, in my early teens, a profound (and monumentally formative, for me) bond between the two of us.

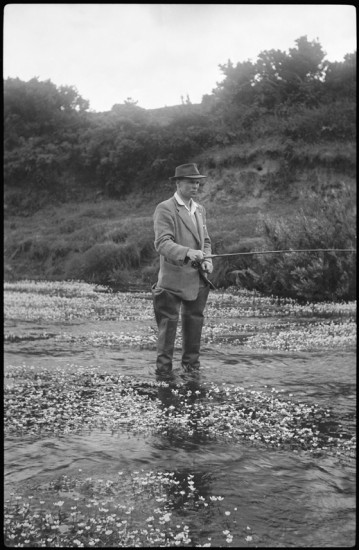

My brother and I saw first hand a red deer stag he shot in the West Country, hanging in the stable of the farmhouse in which we were staying, and we accompanied him on successful shoots; my brother as an official beater, me mostly with a camera and by then long haired ambivalence toward that particular sport (an ambivalence at least partly shared by the old man, who far preferred the solitary even handedness of a deer stalk to the pseudo machismo, snobbery and “set-up” of so much pheasant shooting). And plenty of big rainbow and brown trout on our ever more occasional fly-fishing trips left us envious of his knowledge, cast and of course, as we saw it, raw good luck.

But it is love and not bloodlust for animals that I will choose to remember him for. Garden birds were treated with as warm a welcome as human guests, wood mice in the garden were fed with apple cores and looked upon with fondness, and I think he took as much enjoyment from looking after the pheasant pens, partridges and other game birds for his shoots, or capturing the beauty of a bird’s plumage, or a butterfly’s colours in his water colours as he did in actually shooting at or catching animals in nets.

I am glad, above all, that the red kites which have almost made a home on the bird tables of our village and that have become such a successful re-introduction story over the past decade or so were able to give the diminishing contact with nature in his last years a touch of both the exotic and the tooth and claw drama that he loved; he never tired of telling me, or latterly his recent great-grandchildren that he had seen a sparrowhawk in the days prior to a visit, even if it had been just a fragmentary glimpse of the bird’s deft, agile flight. And I will also remember the many stories. Stories of fishing and walking trips in India, the Lake District or Scotland and being read to as a boy from Jim Corbett or Gerald Durrell (that arch hunter turned conservationist and the pre-eminent naturalist-storyteller); and stories of the war, and the Navy; and plenty of made up stories, too. He was after all, like all the great storytellers must surely be, first and foremost – a fisherman.

Henry Cecil Roy Donne was born in January 1926 and died on Wednesday 26th, 2011.