by Malachy Tallack

While we may have exchanged money for this house and garden, it was clear from the start that our ownership could never be exclusive. Our title was a limited one, and meant less than nothing to those long-established occupants with whom we would be sharing our new home. Seen from their side we were, at best, neighbours. At worst, we were squatters.

It was the crows that told me this. Looking down from their places amid the pines and spruce they watched us arrive, unload our belongings and begin the job of settling in. The crows observed us and they discussed among themselves. Their claim to this place was inherited, and as old as the trees in which they perched. It was the family seat, I suppose. They would let us stay, it seemed, but not without reservations.

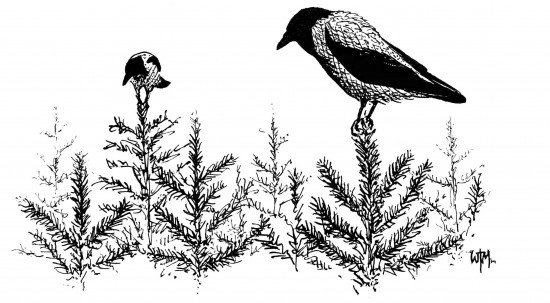

Crows are intelligent birds, like all corvids – rooks, ravens, jackdaws and the rest. They are curious and creative, driven by something more than mere instinct. They fly, sometimes, just for the joy of it, and they can remind us of ourselves if we let them.

This particular branch of the family, corvus coronix, the hooded crow, has a reputation as a trouble-maker – mischievous, and dangerous even. It is an expert and ruthless scavenger, and for its sins the bird has long been considered a symbol or even a harbinger of death. For many it has been an unwelcome sight. But not here. And not now.

On the last afternoon of September, I stepped outside into the garden. The air was warm – as warm as the best of the summer – and the sky was a sweet, syrupy blue. A light autumn wind combed the loch below the house, and a few yellowing leaves were beginning to curl onto the lawn.

Across the road two hoodies were huddled on a telephone wire – black birds with grey apparel. Another passed by in flight and kraw-ed, its voice zigzagging across the valley like dark lightning. In the field beside the house, a fourth crow tiptoes through the grass on his way to nowhere. Then pauses. Then begins again. Like a country pastor consumed by some troubling question of scripture – head bowed, hands tucked neatly behind his back – the bird shuffles about the field. Here and there it stops, stoops, picks up some unfamiliar object in its beak, then returns the item carefully to the ground.

A cry behind makes me turn towards the lower part of the garden – ‘the forest’, we call it, relatively speaking. Around the tree tops a crow coils, flapping and cawing urgently. It burrows down among the branches, then up again and over. The voice is coarse and insistent – a provocation, it seems – and the manoeuvre is repeated, once, then twice.

The challenge evidently succeeds, for out of the muddle of needles and limbs comes a sparrowhawk, as though fired from a cannon into the sky. In an instant, the pair turn about each other, coiling and gyring, their paths wound and tangled in tightening nooses of air above the garden, until it is no longer clear who is chasing and who is chased. The hawk’s screams, thin and needle-sharp, are all that escapes this knot of feather and flight.

By the time the crow tires and swoops away over the loch, I have come down among the trees and hidden myself as best I can. When the hawk settles, it is to a branch just ten metres from my head. I turn slowly and lift the binoculars to my eyes. I can see the dark bars upon the tail and breast; the upright, alert posture; the restless yellow eyes.

The bird is still for a moment and then relocates a little further away. Again, I rearrange my position as discretely as possible, but this time I am seen. The hawk responds, hunching and twitching in my direction. A second’s hesitation and it is gone. Looking down from high above me, it identifies the threat, then pushes east over the water, pursued once more by the crow.

Later that evening I returned to the garden, torch in hand. Dozens of birds gather here at dusk to roost, and in the darkness the place feels alive with them. Crows bluster like grey ghosts among the branches. Invisible wings gust from limb to limb.

I cast the torch beam up among the trees and swung it back and forth, carving brief holes in the night. Through them, I saw strange, distorted fragments of the world that I could hear, and I felt lost for a moment, and a long way from home.

But then the beam alighted on an unexpected thing, and I understood at once what before had been unclear. For some weeks our sleep had been punctured by cries from outside – serrated shrieks that burst through the half-open window. But I had not, until that moment, identified the culprit.

In the upper branches of a Norway spruce stood a heron, looking huge and ridiculous and perfectly handsome. The bird twisted its long neck, awkward in the light, and squawked. A few seconds later and another squawk came, this time from another bird, close but unseen.

I flicked the torch off and waited a moment longer, letting the darkness settle down around me. Once my eyes had re-adjusted, I slipped back across the lawn towards the house, leaving behind an unfamiliar garden, two herons, and a night full of crows.