Caught By The River’s Robin Turner – along with co-conspirator Paul Moody – set out on a Search For The Perfect Pub. Using George Orwell’s 1946 piece The Moon Under Water as a routemap, the pair travelled the length of the country talking to publicans, politicians and pop stars about why that most British of institutions remains such an important part of our culture. In this exclusive extract, the search takes Robin to a boozer stuck out on Lundy in the Bristol Channel.

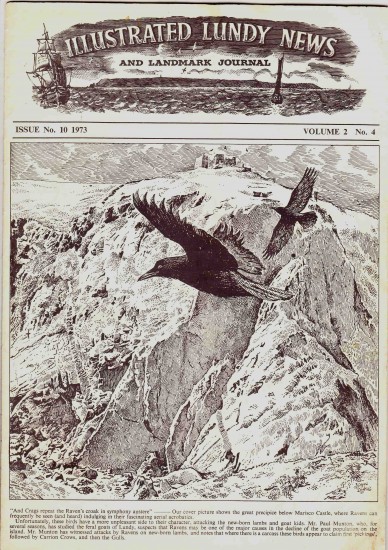

When there was a perfectly good local just a tempting sixty second stroll from your front door, four hours each way on a boat did seem a hell of a long way to go for a pint. Lundy lies somewhere near the middle of the Bristol Channel, popping up roughly due south of Tenby and about 12 miles off the north coast of Devon. England’s first marine nature reserve and home to all manner of birdlife, Lundy was nominated as the country’s tenth best natural wonder in the Radio Times. There, puffins could occasionally be seen coasting along the surface of the sea, mouths stuffed with silver skinned fish. Grey seals would wallow in the protected waters just away from the harbour. That was obviously all wonderful, but most important of all was the fact that Lundy was home to arguably the country’s least accessible boozer.

If Orwell was truly searching for a pub that “drunks and rowdies never seem to find their way” to, the Marisco Tavern genuinely went some distance beyond his criteria. There was no short cut to get there – well, not one that wouldn’t cause you to wince at the price (as with the twice weekly chopper flight from Hartland Point). Crossings could be cancelled with little warning if weather conditions turn squall-ish. My first and second attempts saw the boat from Ilfracombe turn away all day passengers. Walkers, twitchers and nature enthusiasts all stepped aboard, ready to brave several days out on the rock. Us drinkers were unfortunately deemed surplus to requirement and left slack jawed and thirsty on the pier waiting for the pubs to open. The onboard bar obeyed no landlocked licensing rules.

My third stab at getting to the Marisco Tavern was to be my final. My determination was by then clouded by the thought that “No pub is worth this must effort, surely?” I decided to change tact by trying to cross from South Wales in the temperate lull of early summer. Luckily on the day the Waverley – a beautifully preserved chug-chugging paddle steamer – glided into view, the Bristol Channel was as smooth and grimy as the opaque glass of a pub window beside an A-road.

The crossing was textbook perfect. After hugging the Welsh coastline from Porthcawl to Swansea, the Waverley forged out towards North Devon, bobbing along purposefully packed full of daytripping Taffs. By the time the boat set sail for the final leg of its outward journey, the majority of passengers on board had been replaced by birders and ramblers from the West Country (the Welsh/North Devonian love in seemed to take place in Ilfracombe. When I next saw the Welshies on the return voyage, they are without exception utterly smashed beyond belief. Having toured the pubs of Ilfracombe and the surroundings when attempting the previous two failed crossings, I was mightily impressed at their steely determination in the face of some pretty rotten boozers).

Lundy was the original craggy island. Looming out of the sea, it stuck out like a giant boulder thrown from the shoreline by a pissed up giant or the back of a terrible giant creature, felled and fossilized by time. It was truly beautiful, perfectly isolated and utterly unspoilt by the bored hands of teenagers. Most disembarking passengers strode off purposefully with the requisite uniform of slung Barbour jackets, well-worn Karrimor boots and hi-tech bins. There was just three hours shore leave; the sound of the ship’s klaxon would sound five minutes before the Waverley’s anchor went up. With so little time, the challenge was how to make the time on the island worthwhile.

I immediately made a beeline for the pub. I figured I could probably see nice birds anywhere. The only hurdle was the 45-degree incline in front of me. Alarmingly unfit and still in disbelief that I was actually there, I pretty much sprinted until I was through the door.

Sinking into my second pint in the Marisco – the first desperately shot-gunned in utter mind-bogglement at my surroundings – I finally manage to relax. I took a seat next to a South Walian sea dog named Pete and asked what had brought him to the island. It turned out, weather permitting, Pete had made the trip out from Porthcawl to Lundy annually for the last forty five years. Pete’s original inspiration for making the trip came from the fact that Wales was once ‘dry’ on a Sunday. As the boat sailed on God’s own day, a booze cruise up the Bristol Channel seemed like a perfect way to make up a round seven days of fully licensed bad behaviour. By the time that the law loosened in the ’70s, the Waverley trip was part of the calendar. When he’s first made the trip, the boat was lawless and extremely lively.

“It wasn’t exactly luxury back then but people made the most of it. They’d arrive carrying flagons of beer, crates of cans, bottles as well. They’d start the real business of the day as soon as they boarded. More often than not, the bar was drunk bone dry before the boat had docked in Lundy.”

He fondly remembered regularly sailing over in the ’70s with a crew of able bodied pissheads that included a one-legged chip shop owner.

“We used to sail en masse- friends, family members and anyone else up for a day out. Always just men too. It was a proper day out, a bit like a sea bound version of the Dylan Thomas story “The Outing” (which is coincidentally pivots around the boat’s starting point, Porthcawl). Our extended drinking family included a chap called Chippy Hawkins. He was known as Chippy because he ran the local fish and chip shop in Bridgend. He’d lost a leg – either in the war or through some booze based misdemeanour, I can’t remember now. Anyway, when the boat arrived he’d get shoved on the back of a flat bed tractor and driven up the hill, across fields and into the pub. He was always the first and always last at the bar… and first back on the boat. Guaranteed to be as pissed as a rat when they plonked him back on board.”

Sat here, taking in the surroundings, it was easy to see why someone like Pete would feel the urge to return time and again – dry Sundays or not. The Marisco was serving the most peaceful pint in Britain. It was the perfect place to clear fog from your brain before clouding it up again with one of the island-only ales specifically brewed for the Marisco by Cornwall’s St Austell. Throw in the odd lock in, a sea shanty or two and some casual liquid-assisted twitching and one could really get used to life as a castaway. Taking a pint outside, the view was grass, sea, far-off land and bird life. There was no noise pollution here, no light pollution at night either. It felt like the most perfectly anti-social drinking experience in the world – all the details of pub life, just none of the people. No rowdies. No drunks.

KLAAAAAAAAAAAANGGGGGGGG!

I awoke from a daze to see the barman of the Marisco stood in the doorway laughing at me. I’d just dreamed my way through the klaxon and missed everyone patiently filing down the hillside. I had two and a half minutes to make the boat, otherwise I was stuck here – homeless – for three days.

It was a very tough call.