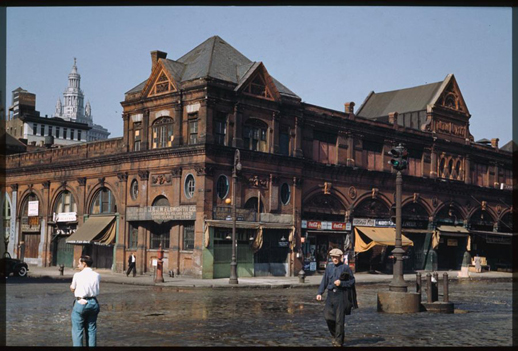

The Old Fulton Market, Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Saturday afternoon (1941)

The Old Fulton Market, Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Saturday afternoon (1941)

Words by Ian Preece

Photographs by Charles W. Cushman

Recently I came across my son’s homework, left up on the computer screen. Designing the cover of a film magazine, he’d emblazoned across the front: ‘Features plenty of reviews, including Cool Hand Luke, The Outsiders and True Grit . . .’ He’s only 13, but I’m beginning to worry I want to spend all my life in a world where people are talking about That Was Then, This Is Now, where, as an icy winds blows off the East River, I can pick up a bushel of black clams from the old Fulton Fish Market; or catch a ferry beneath the peeling paint of the Lackawanna Ferry terminal, eat blueberry pancakes in the silver-caravan diner on Great Jones Street; basically, to walk down the street in a Charles Cushman photograph, a world of pale skies, brownstones and parked Buicks, where every man is wearing a suit and a fedora . . . and Joseph Mitchell is still writing for the New Yorker.

South Street teems with trucks along East River, New York City (1941)

South Street teems with trucks along East River, New York City (1941)

I say ‘still writing’, but Mitchell famously spent the last thirty years of his life turning up at the New Yorker every morning in his trademark jacket, tie and hat, closing his office door and sitting down to type. He died in 1996, aged 87, after 58 years at the magazine, but his last piece of work came out in 1964: Joe Gould’s Secret, which is the final book in the new Vintage Classic edition of Up in the Old Hotel, a collection of four of his books rolled into in one.

Residents of lower Clinton St near East river, Saturday afternoon (1941)

Residents of lower Clinton St near East river, Saturday afternoon (1941)

Joe Gould’s Secret details the life and times of its eponymous Greenwich Village character, by turns a rheumy-eyed hustler, Bowery bum, poet, raconteur and authority on the language of seagulls, who nevertheless possessed a searing insight into human foibles, and a sharp enough wit to keep the wolf from the door (just). Mitchell had been an acquaintance of Gould’s for years, had first profiled him in the magazine in 1942, and the New Yorker reporter was someone Gould would hit upon for a sandwich and a beer. In fact, Gould spent much of his time getting by off friends, largely village ‘radicals’ whose pretensions he could see right through. He was forever at work, so he professed, on a vast Oral History inspired by something he’d read by W.B. Yeats: ‘The history of a nation is not in parliaments and battlefields, but in what people say to each other on fair days and high days, and in how they farm, and quarrel . . .’ Gould’s ‘secret’ ‒ and one of the first to suspect it was Mitchell ‒ was that the ‘9 million words’, a life-time of observation and assiduous recording, only amounted to a few scraps of paper. Gould seemed to spend most of his time lugging around his tatty binders, scribbling away in bars for tourists, forever engaged in re-writing a piece about the death of his father and another concerning a conspiracy theory on the consumption of tomatoes; he’d then bum another beer, annoy another waitress, end up back in the flophouse.

East 7th St between 3rd & 2nd St. (1942)

East 7th St between 3rd & 2nd St. (1942)

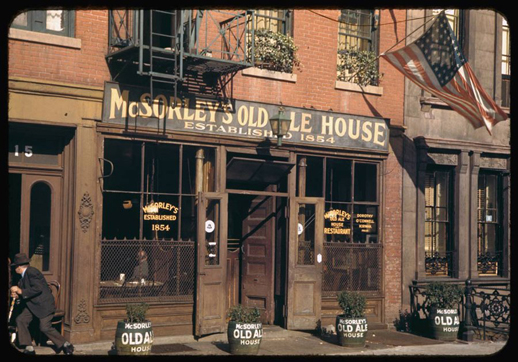

Skimming the internet it’s possible to harvest various theories on exactly what Mitchell was up to at the New Yorker, post-Joe Gould’s Secret, typing away behind his closed door: some say the office cleaner would regularly pull reams of paper out of the bin; others that he had writer’s block; still more held to a general feeling that whatever epic account was fermenting in there, it would certainly be worth the wait. Of course, it never came, and it’s hard not to draw parallels in a kind of inverse way with the plight of Gould’s Oral History: Mitchell’s early output was prodigious ‒ never can a journalist have given up so much of himself to recording his subjects’ lives; sometimes you wonder if he had a home to go to ‒ and by the time he came to write his book on Gould he’d interviewed so many Greenwich Village bohemians over the years he’d begun to find them ‘surprisingly tiresome’. The Yeats quote can stand in for much of Mitchell’s collected writing; but his weariness of his subjects later in life is revealing not only in terms of his ‘drying up’ but also in highlighting the one fault of the first book, McSorely’s Wonderful Saloon (1943), the first volume re-printed in Up in the Old Hotel. McSorely’s . . . is an expansive, exhaustingly detailed collection of his early New Yorker features; a compendium of the lives of various nuts, eccentrics, bearded ladies, Plutarch-reading child prodigies, scrubbers, slappers, Russian gypsy patriarchs, Calypso singers and Caughnawaga Mohawks ‒ steel riveters responsible for much of the horrifically dangerous construction of bridges connecting Manhattan to the boroughs in the twenties and thirties. The book has been described as Mitchell’s Dubliners, and the only complaint is that Mitchell, being a scrupulous recorder and even-tempered type, has his notebook open to all; he accords equal amount of breathing space to Village ‘characters’ as he does to the nomadic Iroquois bridgemen swaying hundreds of feet precariously above the Hudson River. There was probably a whole book in the beauty and the sadness of ‘The Mohawks in High Steel’, whereas you feel you’ve grasped enough about Commodore Dutch, who organised naval balls and galas in his own honour, and Johnny Nikavov, self-styled gypsy king of 38 Russian families, in just a few, exhaustively detailed pages.

A block between Avenues A and B (1942)

A block between Avenues A and B (1942)

Still, stick with it, as what slowly develops is the emergence of Mitchell’s own voice, and a sense of pathos, of the sheer dignity with which he imbues his character’s lives; an absolute sense of the beauty of the old world, barely grasped, before the crushing march of time and ‘progress’ . . . all of this inundates the later pages of McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon, Old Mr Flood (his ‘truthful rather factual’ blending of several real-life characters, from 1948) and his masterpiece The Bottom of the Harbour (1960) like a spring tide bearing silver-blue shad from the Atlantic, through the Narrows and up the Hudson River.

‘One day in late February,’ Mitchell writes, at some point in the late-fifties, ‘the weather was surprisingly warm. It was one of those balmy days that sometimes turn up in winter, like a strange bird blown off its course. Walking back to my office after lunch, I began to dawdle. Suddenly the idea occurred to me, why not take the afternoon off and go over to Edgewater and go for a walk along the river and breathe a little clean air for a change. I fought a brief fight with my conscience, and then I entered the Independent subway at Forty-second street . . .’ He takes the bus over the George Washington Bridge, and once above the riverbank he can see smoke coming from the stovepipes of various fishermans’ barges. He stops by the barge of his friend Harry, a wizened old riverman, for a coffee. Here’s Harry, on waiting for the shad:

‘Quite often, we’re way too early [to lift the net]. We might sit there an hour. If it’s during the day, we sit and look up at the face of the Palisades, or we look at the New York Central freight trains that seem to be fifteen miles long streaking by on the New York side, or we look downriver at the tops of the skyscrapers in the distance. I’ve never been able to make up my mind about the New York skyline. Sometimes I think it’s beautiful, and sometimes I think it’s a gaudy dammed unnatural sight. If it’s in the nighttime, we look at that queer glare over midtown Manhattan that comes from the lights in Times Square. On cold, clear nights in April, sitting out on the river in the dark, that glare in the sky looks like the Last Judgment is on the way, or the Second Coming, or the end of the world . . .’

Lower Manhattan from Jersey City ferry boat (1941)

Lower Manhattan from Jersey City ferry boat (1941)

In the Bottom of the Harbour Mitchell vividly captures the sunny, crystal clear New York mornings, of residents of Harlem and the Bronx fishing for tomcod on the banks of the Harlem river, of brutally ugly, hairy-snouted sea sturgeon leaping and clearing the waves, of wrecks of old ice, coal and slaughterhouse barges, waterlogged and sitting ‘like hippopotamuses in the silt’; it’s a world of warily suspicious yet fiercely proud dragger captains who know the bottom of the river like the palm of their hand, and who end up passing on significant knowledge to marine scientists before, deeply satisfyingly, attaining éminence grise-like status in oceanography themselves. There’s the changing of the seasons, and the endless flow of the water, the disappearing world of real Italian baked bread, of Fire Island Salts, Rockaways and Shinnecocks (infinite varieties of Oyster), and, all the time, Mitchell in his fedora, notebook tucked in his pocket, riding in the lorry with a load of shad or lobster on the way to the Lower East-side market; watching the sorting of the catch and the hosing down of the quay outside; hanging out with the old-timers and stallholders; or just stalking the banks of the East River, or the Jersey shore of the Hudson, where, wandering across the rusty tracks of old freight yards, he can get closer to the water:

‘I often feel drawn to the Hudson River, and I have spent a lot of time through the years poking around the part of it that flows past the city. I never get tired of looking at it; it hypnotizes me. I like to look at it in midsummer, when it is warm and dirty and drowsy, and I like to look at it in January, when it is carrying ice. I like to look at it when it is stirred up, when a northeast wind is blowing and a strong tide is running ‒ a new-moon tide . . . and when it is slack. It is exciting to me on weekdays, when it is crowded with ocean craft, harbour craft, and river craft, but it is the river itself that draws me, and not the shipping, and I guess I like it best on Sundays, when there are lulls that sometimes last as long as half an hour, during which all the way from the Battery to the George Washington Bridge, nothing moves upon it, not even a ferry, not even a tug, and it becomes as hushed and dark and secret and remote and unreal as a river in a dream.’

Mitchell charts the sad decline of the oyster beds around the bay and the general rise of oil, grime and filth on the water. He writes brilliantly about rats in New York and of the mud in the Gowanus canal where, ‘the sludge rots in warm weather and from it gas-filled bubbles as big as basketballs continually surge to the surface. Dredgermen call them “sludge bubbles”,’ and recounts the sorry tale of the mossbunker (‘not a good table fish’), which is like herring but too oily and bony and ends up ‘a factory fish’, pulverised into making soap, paint, ink and meal for pigs . . .

When not hanging out with Italian restaurant owners or bartenders in the Village, Mitchell could often be found eating shad-roe omelette, split sea scallops ‘or some other breakfast speciality’ with the proprietor in Sloppy Louie’s, the faded but, you sense, still beautiful restaurant opposite Fulton Fish Market. He is great on turtle stew, beefsteak parties (wild Saturday night affairs of ‘stylized gluttony . . . all you can hold for five bucks’), clams and clambakes (in August 1937 he came third in a clam-eating competition and came to consider this ‘one of the few worthwhile achievements’ of his life), and produces an incredibly moving account (‘Mr Hunter’s Grave’) of life in an isolated black community on Staten Island. Here the fragile sense of a world about to disappear is almost overwhelming, as Mitchell wanders around graveyards identifying long-forgotten wildflowers and weeds like peppergrass, and studying distant family connections on cracked and mildewed headstones. He becomes acquainted with octogenarian Mr Hunter, the last of a long line of black oystermen who worked the beds off Staten Island, and whose heartbreakingly cheery presence, generosity and fine home-baked lemon-meringue pie mask a life of terrible loss and loneliness.

Mitchell wanted to record a world gone by, one fast disappearing under huge casts of concrete ‒ he later became obsessed with old buildings, literally clinging on to door-handles, bath-taps, fittings, cutlery, even pickle-forks (!) from the ruins of derelict hotels and factories ‒ and to fix for ever, and not without great dignity, the lives of ordinary folk. He was once asked why he wrote about ‘little people’. There were no ‘little people’ in his work, he replied: ‘They are as big as you are, whoever you are.’ By the forties he was shaping his material like a master craftsman. His writing was clear like an upstate stream; as direct as a downtown rap sheet. As William Fiennes writes in his introduction to Up in the Old Hotel, Mitchell had no time for ‘“tinsel words”. He didn’t want to write “representative of the vice ring”: he wanted to write “pimp”.’ As is often the way in this world, in later years Mitchell usually ended up dining alone at lunchtime (in the Grand Central Oyster bar, naturally). Up in the Old Hotel should be a set text on any journalism course: it throws into painful relief the shameful state the media has got itself in, the contempt news organisations treat ordinary people with today . . . My favourite quote about Mitchell comes from the New Yorker stalwart John McPhee: ‘When the self-proclaimed “New Journalists” landed on the beach with their novel insights into non-fiction writing, Joe Mitchell met the boat. He was ahead of them in time, artistry and range.’

He watched the boats, the lights from the shore, people’s lives; he knew the ways of the river, knew his New Jersey Shrewsburys from his Rhode Island Narragansetts . . . But, above all, Mitchell was just concerned with the stuff of life; or, to quote Harry, the riverman from The Bottom of the Harbour: ‘As far as I am concerned, the purpose of life is to stay alive and to keep on staying alive as long as you possibly can.’

———————————————————————————————————————————

Up in the Old Hotel is published by Vintage (Sam Stephenson’s piece on Joseph Mitchell from a 2008 edition of Oxford American: The Southern Magazine of Good Writing, Edward Helmore’s obituary of Mitchell in the Independent and Tim Adams’ feature from the Observer, were invaluable sources of information.)

The book is on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £11.99