In which, as the year comes to its end, our friends and collaborators look back and share their moments:

Anyone who actually knows me might be a little shocked to read that the two most important events of 2012 for me were both sporting ones. To the uninitiated, I’m not sporty. Far from it. My brick shithouse-gone-to-seed physique is something that’s been carefully nurtured over many years in darkened pubs; going for gold has always been less a life’s calling and more just that glorious advert for the United States of Europe that my best mate and I dopily tuned into during our student years. To anyone scoffing at my massive volte-face (school friends, distant relatives, Man U fans who I’ve babbled on to drunkenly while they try to concentrate on the match) – it’s as much a shock to me as it is you.

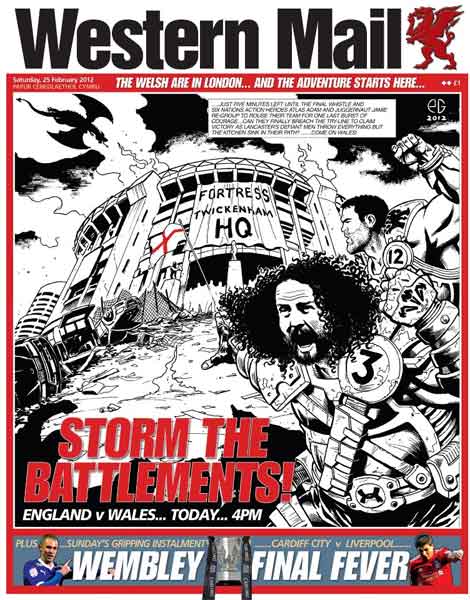

Although it seems like an age ago now, back in March Wales won the Grand Slam. A victory for Wales in the Six Nations is about much more than just sport. If it’s a cliche to say that rugby is our religion, that’s probably because cliches usually cut straight to the point. The sport is revered, it represents true community amongst followers and it always arrives – and departs – with the same kind of self-flagellation that accompanies religion. And it gets us all eventually, no matter how much one tries to avoid it while growing up. That might be because when things are good on the field, something extraordinary happens to the entire country. Witnessing a Grand Slam win, you practically feel the convulsions from wherever you are in Wales, north or south, east or west. You see a furrowed browed nation become wide-eyed and for a brief moment – maybe a day, maybe a week – the whole country’s glass looks something dangerously close to half full. And this year’s slam coming so soon after a bitter KO in the final stages of the World Cup… well, it went some way towards placing the world back on it’s axis. Because when things are bad – as they were in the hangover after the World Cup – they really are very bad.

I’ve witnessed three Slams as an adult. The first was celebrated in a South African theme bar in Covent Garden (2005), the second in my dad’s local (2008). This time, I decided to try to my luck at the London Welsh Centre on Gray’s Inn Road. If you’ve never stepped foot in a proper Taff working men’s club then a visit to the upstairs room of the London Welsh should give you a pretty deep hit of Valleys bonhomie. A combination of bad Brains (ill kept Welsh beer not the D.C. hardcore band), a barely functioning telly and seemingly every Welsh man, woman and child in London stuffed into an upstairs room the size of a tube carriage (the cavernous downstairs hall had been absentmindedly double booked for a Welsh for Beginners course – attendance 11 people) made the place truly feel like home. We like a certain hairshirted-ness, us Welsh – anything fancy makes us feel uncomfortable. Rugby back home is still a predominantly working class pursuit, watched in legions, men’s clubs, pubs and front rooms. The glamorous world of team members marrying minor royals is as alien to our version of the sport as tales of public school fagging.

The match – like all the matches in the 2012 Six Nations – was hard won. France came to Cardiff to beat us and we wanted blood after the previous year’s defeat in the World Cup semi finals. With the roof open on the stadium (their request) and some typically chaotic weather that helped make the pitch a near quagmire, the end of the eighty-minute bout couldn’t come soon enough. When it did, the mangled, elated gargles from the upstairs room of the London Welsh could probably be heard in the 16th Arrondissement.

But, this being Wales and the Welsh Zen always being fleeting, the half-full glass was soon downed. Then smashed into the floor with bare feet. Then pissed on before being set on fire. During the much hyped Autumn Internationals, our side was in a right mess. What’s worse, England are now looking venomous and will surely be coming to Cardiff to screw things up for us in March. If the dream hasn’t quite died then it’s certainly quite some way away, out there beyond touching distance.

A few months after the Grand Slam dust settled, I found myself sat in a sports stadium a mile or two from my home in Hackney watching the dress rehearsal for the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games. I carried a confused perspective on the games. The idea of a month of sport, flag-waving jingoism and a terminally choked up London made me want to lock up the flat until September. Even so, there was one thing that ensured I couldn’t write it off.

For the last two decades, I’ve worked with the opening ceremony’s musical directors Underworld. In the nine months running up to the Games, I’d been signed to a non-disclosure agreement with regards all things Olympics. It stopped just a touch short of threatening “pain of death” and it meant I’d find myself in clandestine meetings with the band’s manager in the one sane haven in Westfield Stratford – Tap East (a phenomenal brewpub at the back just by the Eurostar terminal – worth scything through the crowds to visit). Meetings generally involved three pints, some nervous forelock tugging (manager, not me) and getting to hear rough mixes of musical ideas.

Over those months – and under the shroud of a palare like code system – I heard talk of how the show was coming together, of the proposed set pieces and the prospective soundtrack. I heard demo versions of Underworld tracks and I threw in a few suggestions of tracks that could work. After each meeting, I assumed that the majority of what we discussed would be kyboshed. There didn’t seem any way that director Danny Boyle would get away with or be able to pull off half of what was under discussion, certainly not under a Conservative led government. Although the agenda was painted with broad brushstrokes, it was clear that there was an agenda.

But, no, on a blistering Wednesday night in late July, there it all was. Frank Cottrell Boyce’s magnificently lyrical premise and Underworld’s brilliantly nuanced score were right there at heart of Boyle’s boundlessly optimistic, utterly pure show. Present and correct were the what-the-fuck impossible mechanics of the Pandemonium section, the something-in-my-eye tribute to the NHS and the mighty Fuck Buttons soundtracking the section where Doreen Lawrence and Mohammed Ali walked the Union flag out. An event where the taste barometer was calibrated by Bowie’s Berlin period rather than the collected works of the people Gary Barlow keeps on speed dial. The contrast with the relentlessly beige Jubilee ceremony that Barlow curated – an evening so achingly bad that Prince Phillip got himself admitted to hospital to avoid sitting through it – was blinding.

I walked away from the stadium utterly overwhelmed. Whatever prior knowledge I’d had really didn’t do the actual thing any real justice. The visual spectacle and the soundtrack were peerless – no one had ever attempted anything quite so bonkers on such a grand scale and got away with it so brilliantly. Looking around the Overground train on the way home, every single person – without exception – was beaming. It felt like we’d all just witnessed the start of something beautiful. And really, we all had.

As the show was broadcast to the world forty-eight hours later, I followed its progress with an eye on Twitter. I watched my close friends – the brilliant writers and hardened cynics (that’s a singular description by the way) – melt emotionally. Everyone was having the same reaction, as if there was a shared hallucination happening in living rooms all across the globe. That beneficent hallucination that seemed to hang over the country for the duration of the games offered a vision of Britain that I actually wanted to take a part in. The ‘multicultural crap’ that shit-for-brains Tory MPs despised on the night of the Opening Ceremony was – is – exactly the kind of stuff that makes me quietly hopeful for the future and, ultimately, very proud to be British.

Which is a lucky because the bloody Welsh haven’t half let me down recently.