by Phil Dunshea

On one of the uninspiring days between Christmas and Hogmanay, my brother and I drove west. We followed the A55 to Wales, to us the most familiar road of all, that floats like an airship over Liverpool and the Wirral, flicks past Little Chefs, untidy sheep-farms and golf courses, then hurls you out into the Vale of Clwyd. We went on, past the tide-wrack of the St Asaph floods and out to the sea. The road took us skulking round the back of Llandudno – screened by low hills, affronted by the expressway – and then under the Conwy. We burst out under the castle walls like a misguided siege-digger, then went south up the valley, looking for trouble. There were clouds on the Carneddau. By our side the Conwy looked as warm and muddy as the Limpopo.

We sought Rowen. We’d been there for several camps with Scouts, years back, and we couldn’t be bothered with one of the real hills further west. Rowen is a several-time winner of tidiest village and Wales in Bloom, and it shows, we thought, as we nosed the car up a one-in-three farm track and Rowen emerged in the rear-view mirror, practically underneath us. We’d overshot. Eventually we booted up outside Ty Gwyn, the pub, and splashed north across deserted fields to Parc Mawr. Smoke was creeping from nearly every chimney in the village, dogs bawled through the drizzle. In the woodland behind the old campsite – which in Scouts we’d christened ‘spooky grove’ one night, only to hear it adopted as ‘groovy wood’ the next – a hollow-way grinds straight up the hillside. We followed up through trees to the edge of a plateau, where the track runs into a pattern of dry-stone walls. They are as dense as anything outside the Aran Isles, all caked with moss and lichen the colour of Fanta.

A few minutes further up we ran into the place we’d been looking for, Llangelynnin. We’d remembered that there was an old chapel up here. It emerges from the landscape like an ancient crab caught in a fishing net. Walls and pathways radiate out to the rim of a craggy hollow that surrounds the site like an enormous satellite dish. It is unmistakably very old, Llangelynnin, and the isolation smarts. We went into the churchyard – a true llan, surrounded by walls that are nearly as high as the church itself – and walked among the low headstones. The epitaphs seemed dislocated, strangely eclectic: someone born in Zurich; Hester Norris, ad montes sursum corda; faded Joneses and Jenkinses; a funny little death’s head emblem. There is a well folded into the wall at the south-east corner of the churchyard, a window of clear water set among the stone slabs, the only thing in the whole valley that wasn’t being thrashed by the wind.

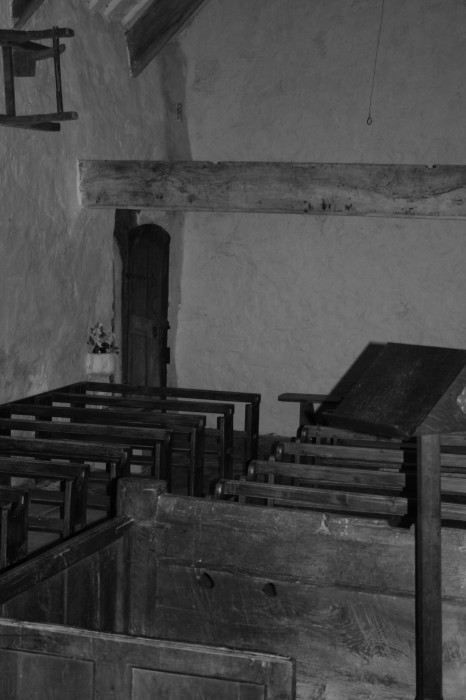

Inside the chapel there was darkness, and the noise of the wind engulfing the roof, booming. But the place has survived enough of these winters. On the east wall, under scrubbed-out white wash, the Creed and the Ten Commandments are written out in Welsh; above the window, ‘fear God and honour the king’ is in English. Lower down, another momento mori casts a sideways glance into the pulpit. Beside the plastic roses on the altar everything is stone, white-washed or bare, and dark old wood. Llangelynnin does not feel like a relic – it is more robust than that, and we could only smile.

The chapel may be eight or nine hundred years old, although it’s hard to tell for sure. Twentieth-century restoration work hasn’t changed the place a bit. To the north of the altar, in the low cavern of Capel Meibion, the men’s chapel, rows of benches climb into the darkness. A horse bier hangs on the south wall, and a stone font crouches behind the door like the stump of a Roman column. Evensong is still sung here, sometimes, in summer.

We sat in the porch, roofed with timber from the yew trees which used to stand around Llangelynnin. Only one tree grows in the churchyard today, a devil-may-care hawthorn that has levered out from under a boulder on the north side of the chapel. Scarlet berries gleamed from its mesh. As we sat two women on horseback made their way along the path beyond the wall and for a moment the atmosphere was broken, Rowen’s vague Cotswold-feel re-asserting itself. Their chatter vanished round the corner. A hundred years ago, Huw Thomas Edwards used to go the same way on his journey to cut stone at Penmaenmawr, eight miles a day there and back. Later he was the Welsh Labour movement’s greatest leader.

We went south-west, though, contouring round Tal-y-fan, sons of a more frivolous time. We wanted to have a look at the Roman road. Its route shows how difficult it used to be to get to Gwynedd: the coast is interrupted by the estuary at Aber Conwy and then by the towering granite of Penmaenmawr, one and half thousand feet high before it was decapitated by modern quarrying. To get around it all the Romans took their road inland. Following an older track, they crossed the Conwy at the fords near Caerhun and drove due west into the hills. As it climbs the road crosses a Neolithic moonscape of field-patterns, barrows and dolmens, already ancient two thousand years ago. It doesn’t have the broad swagger of the Roman roads in Britain’s lowlands, hammered into the land with aggregate and mortared-stone; this one is furtive, barely scraped wider than its predecessor as it heads up to Bwlch y Ddeufaen.

Bwlch y Ddeufaen is the Pass of the Two Stones, where twin menhirs stand in a wreckage of low stonework. It’s hard to tell man’s handiwork from nature’s here – there are stone circles in the tussock-grass that you can’t see until you’re actually standing inside them. The Roman milestones that were found up here, long since carted off to museums, must have looked very odd surrounded by all this debris. Well into the nineteenth century the pass was well-used, with cattle drovers taking their herds to markets in the east, many of them after crossing over Traeth Lafan from Ynys Môn. But a road was blasted through Penmaenmawr, and the Conwy was bridged downstream from Canovium, so there’s no need for anyone to drag themselves up here nowadays. Two pylon lines carry power humming through the gap towards Bangor.

Like brigands, we dropped down onto the road from above; the hikers exerting themselves towards Bwlch y Ddeufaen seemed surprised to see us tumble off the hillside. The line of the road was given away by a much older landmark standing beside it, a cromlech called Maen y Bardd. The pi-outline of its boulders was unmistakable: last time we were here we’d sunbathed on its top-slab for hours, but today it was slippery, and stank of sheep shit. Cwrt y Filiast, the greyhound’s kennel, is its other name, and that seemed better to us than the ‘poet’s stone’. We jumped down into the trench of the road. In the field opposite a single standing stone looks south up the Vale of Conwy, where patches of sunlight were swarming over hillsides. Turning north-east, treading after Maxen’s legions, we followed the road through fields of knackered farm machinery, and then dusk.

Philip Dunshea is a writer and historian, specialising in the landscapes and history of Northern Britain. For more details click here.