Illustration by Jonathan Gibbs

Words by Neil Sentance

1995: North End, part 2

An old hose stood limp by the cattle byre. Past the turnstile gate, the reek of dried manure still hung in the air. How many beasts passed through here during the life of North End farm, their hooves clattering on the broken-brick ground? In the 1960s grandad bought most of his stock from Scotland. They would be sent south by train and he would collect them at the halt station at Sedgebrook, and walk them the five miles to the farm via Allington and over the Great North Road, the A1, stalling traffic to Leeds and London on either lane. Behind the central courtyard, where the cattle overwintered, was the crew yard, the site of calf longboxes, brick pens and sheds for calving and rearing youngsters. Adjoining that was the double-storey bullpen, with a ladder for outside access and spy-window for looking down on the bull, a caution no doubt inspired by family history, our own old testament fable, the death of grandad’s father trampled by his own prize animal. I recalled now the boyhood thrill of climbing the ladder and peering through the window and into the abysmal depth of the bull’s eyes.

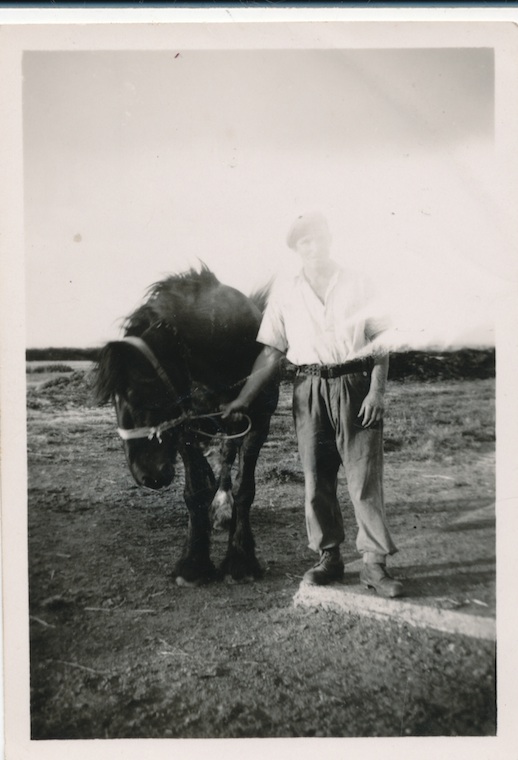

Grandad and heavy horse, 1940’s

Grandad and heavy horse, 1940’s

I didn’t venture into the empty byres but walked through the open, skeletal Dutch barns erected in the seventies. A few relic straw bales, faded and fibrous, were stacked in a corner. Here the heavy plant used to be stored, the treacherous-looking threshing machine superseded by a pillar-box red combine, and the hulking modern Canadian tractors. Sometimes during harvest time grandad would have me up in the cab with him, where he’d have Test Match Special loud on the radio as we swathed through corn like West Indian bowlers through English batsmen. Grandad had a particular affinity for ‘Fiery’ Fred Trueman, former Yorkshire and England fast bowler, then self-styled sage of the commentary box. He shared his conservative politics, a certain bloody-minded estimation of modern mores and the odd distinction of them both weighing in at an eye-watering 14 pounds at birth…

The familiar unvarying cooing of collared doves brought me back into the stackyard. The wooden door to a storeroom was opposite, once painted red and now washed out to a peeling pink. In front of this door I used to haul a large plastic drum, makeshift stumps for games of barnyard cricket with my cousins. The batsmen’s aim was to smite the ball into the haystacks and watch the fielders scurry over the bales in search of it; or better, a long straight hit over the farm gates and into Fallow Lane, a lordly six-and-out. Only miscues to the offside were discouraged – here were the glasshouses, some days the tempting sector of brinkmanship and bravado, but usually a glinting minefield, like the wrath of grandad, best avoided. Sometimes grandad would watch and encourage from the sidelines, throwing in mystifying references from his own youth: ‘that was a Denis Compton shot’ or ‘that turned a mile, a real Hedley Verity’. Once he was persuaded to turn his arm over, which he did with a hard-won smile, but the gnawing joint pain was all too visible and he soon wandered off to the greenhouses, all economy of movement, and expression. Cricket provided our common language and hunting ground – we could meet out in the middle and nowhere else.

I noticed that the tendrils of a climbing plant had curled up the panes of the greenhouses. These had been an extension of the farm garden, something like what the ancients called the hortus, well worked and manured ground that my grandparents worked hard to make tidy and decorous as well as productive and fruitful. During the war, and for some time after, Italian prisoners worked on the local farms, replacing villagers who had left to join up or work in armament factories. Grandad had two men from Liguria help him in the rationing years – watering those feeble sun-starved tomatoes and staking out the bean poles, how must they have dreamed of succulent zucchini, sweet bell peppers, bunches of aromatic basil and rosemary for remembrance…

Moving on, I went over to the chicken huts, part hidden behind high nettles. Some of the huts were on corroded wheels from the time when they’d be repositioned across fields to provide an even composting. There was also a large corrugated poultry shed, another place of terror for me as a young boy, the roosters seeming as tall as me in their strutting cocksureness, their beaks angular and quick to peck, their faces an angry red – I would hide timorously behind my grandmother’s skirt as she fed them from the pail, and silently sympathise with the bantams cowering in the rafters. Grandad once told me he long ago knew a chimney sweep who used to send live chickens down smokestacks, their panicked flapping dislodging soot on the descent, but I never knew if he was pulling my leg.

Behind the huts was the wall of locally made bricks with stone copings, and a tall wooden fence with a gate to the neat cottage where my mother had grown up. Next to the wall was the former dovecote and workshop, eighteenth-century vernacular buildings and survivors from a previous farm. Here grandad stored tools and old brass collars from the pre-tractor age of heavy horses, and engreased spare parts for long-scrapped Fergusons and Fordsons. In here he would also make cack-handed tool repairs on a splintery bench lined with woodworm like an Arabic script. Everything had been neatly arranged on the Georgian dresser with Greek key mouldings or from hooks in the unplastered wall, a hymn to orderliness, a reflection of grandad’s daily stubborn wrestle with nature and life in general. Now there was a general air of dereliction, as if the mellowed bricks knew they’d soon be demolished to red dust.

I walked on and peered into the corrugated land rover shed, though the 1960s vintage model had been sold off years before. I remembered the gaps in the canvas that someone said were bullet holes. Opposite was the old granary and drying shed, where the harvested corn was deposited late summer nights, the air fizzing with chaff in the headlights. The dryer was a hot, seed-cloaked, echoic place at harvest time and it was here that the epic battles with rats played out – I remembered seeing the dead ones lying by the wall, electrocuted after chewing through armoured cables. This was the earnest business end of farm toil – for grandad, happiness was a full grain store and a good price at market. Now the shed was an empty shell, the windsock sagging against the wall.

*

That last day in 1995, I leant on the five-bar gates, my back against the hand-painted North End Farm sign, and looked over the ghost of a cricket pitch that my grandfather had bestrode in the forties and fifties, long since ploughed up into another solemn field. Small farms were dying all over the country, victims of food and health scares and agglomerating big business. I wondered if grandad would be left another chuntering old farmer in an overheated bungalow, a rambling rose round the front door and a fish pond out back. In the weeks before leaving North End I remembered the day he discovered a mass of ants in the living room carpet, carried in on a flower pot. He worked himself up into a frenzy, manically hoovering up the ants, and then burning the dust bag out in the yard, a strange crematory rite that summed up so much of his attitude to the nature he had spent his life working with, or battling against. By this time, I had left the area, gone to college and settled in the South – as Richard Benson says in his memoir The Farm, I had long felt here like the village idiot with O-levels. And although I had been desperate to escape the loneliness of my homeland, I still felt a strong place-attachment to the farm’s sturdy topography of work and play and the joy of its open country, in a time out of time. One summer when I was staying at the farm, aged around eight or nine, my grandmother woke me in the middle of the night and beckoned me to the window. Over towards the river the sky was a ragged fluorescent lightshow, roving waves of blue-green radiance in a sea of cold white stars. We stood for a long time, imprinting the shared experience, the Northern Lights rarely seen at this latitude. But in the morning the sky was deadbeat and unravelled, the colour of cut hay. This last time at the farm had the same numbness. For all the encrustations of time, all seemed weightless, made only of smoke, and those days seemed done.

A near two decades have since followed and thoughts of my happy childhood and lonesome adolescence have receded as I watch my children seek out their own touchstones, their elemental places, to run and play in the fields and by the rivers three hundred miles southwest, on days of sun and rain, where sky and water meet.