Adrian Mole: An Appreciation by Will Hodgkinson

Sue Townsend got me reading books, and I’m fairly sure I’m not the only one. To my parents’ despair, I had succeeded in reaching the age of twelve without reading a single book. While my brother Tom quoted from George Orwell’s 1984 or Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World every time we did so much as run out of Shreddies or get a new labour-saving home appliance, I felt that all the intellectual stimulation anyone could want or need was contained within the pages of 2000AD. Then along came Adrian Mole.

The Secret Diary Of Adrian Mole aged 13 3/4 came out in 1982, when I was twelve, and it’s funny even before you get to the first page. Which child can’t relate to the innocent pretentiousness of that fraction in Adrian Mole’s age? Then we’re straight into perfect comic writing, the profound and tragic pains of adolescence distilled into hilarious diary entries by a slightly precious teenage boy.

“My father got the dog drunk on cherry brandy last night. If the RSPCA hear about it he could get done,” Mole begins, and in that handful of words Sue Townsend invokes absurd paternal irresponsibility (the drunken dog), woefully suburban attempts at sophistication (the cherry brandy), fear of authority (the RSPCA), and vague malaise (Mole’s alarmist tone.) She follows it with the dominating concern of every teenager: “Just my luck, I’ve got a spot on my chin for the first day of the New Year!”

Adrian Mole gave voice to the kind of problems most of us suffered through but were far too gauche to tell anyone about. There is his parents’ depression and his father’s unemployment, his unrequited love for the sophisticated, annoyingly smug Pandora, his sense of inadequacy against his (ever so slightly) cooler friend Nigel, his torment at the hands of school bully Barry Kent, and most of all his constant suspicion that he always get far less than he deserves.

It looks like Mole’s moment has come with The Voice Of Youth, his short-lived school magazine. Containing a shocking exposé on Barry Kent (“I have mentioned Barry Kent’s sexual perversions — all about his disgusting practice for showing his thing for five pence a look”), a punk poem from Claire Neilson (published anonymously because her dad is a Conservative councillor) and an incredibly boring article on bicycle maintenance from Nigel, The Voice Of Youth is Mole’s attempt at greatness. Needless to say, it all comes crashing down pretty quickly.

“Five hundred copies of The Voice Of Youth were on sale in the dinner hall today. Five hundred copies were locked in the games cupboard by the end of of the afternoon. Not one copy was sold! Not one!” Eventually, one is sold — to Barry Kent. He wants to discover the truth about himself. “He’s a slow reader so it will probably take him until Friday to find out,” Mole predicts, sniffily.

Sue Townsend proved that clear and accessible prose, free of obfuscation or elitism, need not be lacking in sophistication. It takes great skill, not only to capture the voice of a neurotic thirteen-year-old with such authenticity but also to represent life with lightness of touch and a comic eye. As Adrian Mole grows up in real time, the books get sadder. His parents have disastrous affairs, his dreams of becoming a great writer fade, he is a single father, his bald spot grows and, in what proved to be the final book in the series, he is facing poverty and cancer. 2009’s Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years is no less funny than its seven predecessors — his mother is writing a misery memoir, A Girl Called Shit, after all— but there is a sense of time running out.

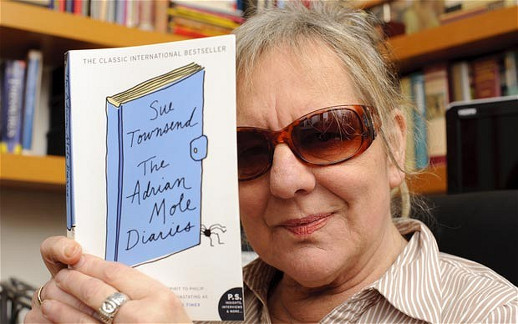

It turned out to be prophetic. Sue Townsend, blind from diabetes since 2001 and writing via a combination of dictation and longhand, was working on one more Adrian Mole book at the time of her death, but The Prostrate Years proved to be the final part of the series. Adrian Mole, the beleaguered everyman, the eternal underdog, was Sue Townsend’s great creation. He was also one of the greatest comic characters in British writing.

I can’t underestimate the debt I owe to Sue Townsend. For years I had been trying to write the story of my own childhood, which was turned on its head around the time I discovered Adrian Mole. When I was twelve our parents went to a dinner party at the house of some fellow middle-class suburbanites, where our father got a bout of food poisoning from a salmonella-laced chicken casserole so severe he almost died, had a Damascene revelation, gave up his job, and began a quest to penetrate the inner core of his being that continues to this day. He joined an Indian spiritual group called the Brahma Kumaris and became a celibate, meditating Yogi, lecturing us on the forthcoming apocalypse over nut roasts and group consciousness-raising sessions. Meanwhile, our mother, rather than do the obvious thing and divorce him, used his transformation as a chance to wage an all-out war on convention. This included promoting her book Sex Is Not Compulsory on prime-time television, just as I was discovering girls for the first time.

I tried writing this up in all kinds of ways — as a novel, as a weighty treatise on spirituality — but nothing worked. Eventually I went back to Adrian Mole, and saw how Sue Townsend never laboured over sad or serious moments but let the events carry their own weight. Slowly, The House Is Full Of Yogis emerged. It’s not in diary form, it’s a memoir rather than a novel, and I can hardly make a claim for Sue Townsend’s comic genius, but if it hadn’t been for Adrian Mole I’m not sure it would have ever been written, let alone published. More than the inspiration she provided, however, the real debt I owe to Sue Townsend is in introducing me to reading for its own sake. By turning pain into hilarity, she transformed reading from something your parents and teachers nagged you to do into something you did because there was no better way to spend a lazy Saturday afternoon. For that alone I’m forever grateful.

The House Is Full Of Yogis is published by Harper Collins on June 5