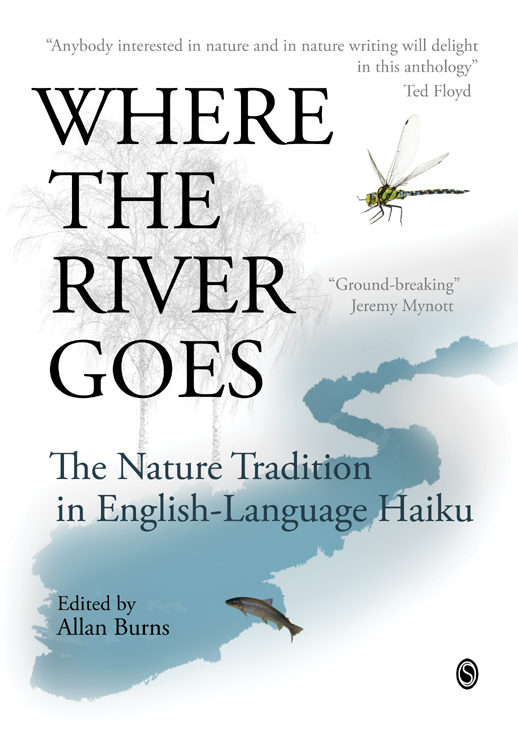

Edited by Allan Burns. Snapshot Press, 2013

Review by Rob St. John

The haiku tradition underwent a transformation in early 1960s, evolving from its Japanese roots to become a meeting point for wider cultural changes and exchanges: a fertile mix of Zen Buddhism, alternative culture, the avant-garde and the green shoots of the modern environmental movement. As Allan Burns, the editor of this new anthology describes: “haiku was seen as an artistic manifestation of this way of seeing the world and our place in it”. Burns’ introduction to the volume outlines how concepts of nature have always interwoven into haiku, tracing origins back to the Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō’s 1680 ‘crow haiku’:

on a bare branch

a crow has settled…

autumn nightfall

Bashō studied Taoism and Zen Buddhism in 17th century rural Japan, experiences which lent a focus on nature’s ‘otherness’ and impermanence to his practice. As Bashō said: ‘The basis of art is change in the universe’. These themes of dynamism and change, of course, are also studied in the environment by ecologists and climate scientists, using a different set of criteria to pick apart and understand the workings of a constantly changing world. Haiku, Buddhism and nature become intertwined in Bashō’s work, and in the tradition that followed, creating minimal, seasonal observations of the world which connect scales both visible and vast: pieces that sit somewhere between the celestial and the terrestrial.

The regular forms of haiku (although this anthology documents an evolving range of structures), offer a seemingly simple, ephemeral lens through which to view and imagine the world. As Burns notes, this structure means that work such as Bashō’s ‘crow haiku’ creates a condition of openness and possibility for the reader to apply their own experiences between the lines of the haiku. I suppose, in this way, nature haiku create imagined ‘middleground’ environments somewhere between the intentions of the poet and the experiences of reader, as the written signposts are only suggestions for the path the reader takes.

Where the River Goes assembles the work of forty poets working in the English language nature haiku tradition since 1963, when the first edition of the American Haiku journal was published. It connects 1960s poets such as James W Hackett, whose ‘mimetic poetry hold[s] the mirror up to nature to capture its reflection faithfully’ through the free, innovative forms of Marlene Mountain’s work, to modern voices such as anthology publisher and designer John Barlow.

Barlow, whose Snapshot Press published a sister volume Wing Beats: British Birds in Haiku in 2008, is one of the few British poets in the anthology, and certainly one of the most enjoyable, straddling the precise and the poetic in his evocations of the British landscape. There’s a similar spirit in the work of American poet Ruth Yarrow, whose work in the 1980s and 90s exhibits a keen naturalist’s eye for the messy, interwoven webs of the natural world.

It would be fair to say the most enjoyable bits of this fascinating but slightly frustrating book are the haiku themselves. In his introduction, Burns lays a decent enough trail of the historical environmental thought, briefly referencing a (largely American) set of writers: Muir, Leopold, Emerson, Thoreau and Carson. His picture of modern environmental issues is pretty problematic though: bleak, Malthusian and perhaps a little hyperbolic, lending a pretty overtly negative foundation to the reading of these haiku. This bleakness is left unsatisfyingly unresolved. How are the collected haiku meant to be a response to these issues? I can’t help think that Burns is trying to impose some ability or agency for environmental or societal change on the collected work: haiku that through their abstract, ephemeral and often vague nature seem to remain largely apolitical.

If the modern haiku tradition is actively engaged with this bleak environmental picture that Burns paints, then where are the climate change haiku? Traditionally, seasonality plays a key role in classical haiku, and it seems to me that the smudging seasons of a changing climate would prove a fertile topic for haiku which actually engages with the grand environmental themes that Burns describes. Perhaps this is overly critical. Maybe these are broader questions: how and why should any artist respond to environmental problems?

At the end of his introduction, Burns cites Aldo Leopold’s suggestion that the challenge for modern conservation movement is to ‘build receptivity into the still unlovely human mind’. Is that the purpose of these haiku then, to foster some sort of positive environmental change or awareness on a personal level? To reassert why nature matters, in a subtle sort of way? To see it in new ways? I guess this is perhaps the case, but the dystopian environments described in the introduction make these themes more than a little difficult to decipher. These questions made me think about Paul Kingsnorth’s ‘Dark Ecology’, and his suggestion that the best response to environmental change for us as individuals is to consciously withdraw from environmental activism, and instead focus on finding our own meaningful, minimal place within the world.

It’s not that I doubt the skill and precision of the haiku contained in Where the River Goes, which are frequently beautiful. Similarly, the book itself is put together with real care and attention to detail by John Barlow’s Snapshot Press. It’s the bleak environmental context in which Burns seeks to ground these haiku that makes their reading a slightly frustrating experience. However, to dip in and read selections of collected authors, all prefaced with insightful biographies, is far more rewarding.

Where The River Goes is on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £18