Andy Childs peels back Sir Edward Grey’s political wrapping to reveal his deep passion for the country life.

“Power should only be entrusted to those who do not seek it” – Plato.

Around one hundred years ago, most weekends, weather and work permitting, the tall, distinguished-looking figure of Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey could be seen fly-fishing on the River Itchen in Hampshire, yards from his modest little cottage less than a mile west of the town of Itchen Abbas. A welcome if controversial distraction for a troubled man, the rest of whose time was spent in London, consumed by the growing political and military crisis across Europe that was threatening to engulf Great Britain.

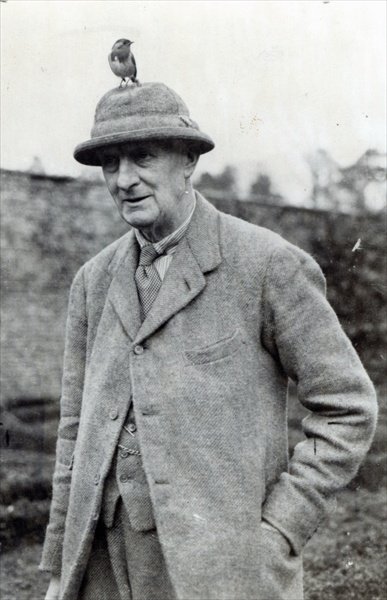

As I discovered in Capital of Happiness: Lord Grey of Fallodon and The Charm of Birds by Jan Karpinski with woodcuts by Robert Gibbins (£2.99 from the Oxfam bookshop in Taunton) Grey was a complex character; a successful politician and gifted in a surprisingly wide range of pursuits, dedicated and capable, but also reticent, reclusive even, increasingly disenchanted with public life and preferring the company of animals and wildlife to people. He disliked working in London intensely and was far happier pursuing his passion for fishing and bird-watching on his beloved stretch of river, away from the clamour of the city and the mountain of paperwork that eventually caused him to all but lose his sight. He was a man, some say, who lacked the decisiveness deemed necessary in politics, and especially the crisis-management brand of politics that prevailed during July 1914 when, as Foreign Secretary, Edward Grey led Britain, via the hazy, fudged corridors of diplomacy into the conflict that so scars our collective memory and preoccupies us still to this day. It was Grey who, having just delivered a compelling speech to the cabinet outlining the inevitability of Britain’s involvement in the Great War, uttered the famous phrase “the lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime” and at the same time no doubt wishing that he was alone and knee-deep in the crystal-clear, watercress-rich waters of the Itchen fishing for trout.

Much as it still does in subtler ways today, position and status in nineteenth and twentieth century politics depended greatly on private influence – who you knew and who your ancestors were. Suitability for the job was also important but often a secondary consideration and although diffident Edward Grey had all the qualifications for a successful political career. Born in 1862 into a family of prominent landowners and steeped in military heritage, he was the eldest of seven children and enjoyed a comfortable, privileged childhood despite the death of his father when he was twelve. Even in his youth Edward appeared to be something of a daydreamer, able but idle, and happier to take part in sport and indulge in the pleasures of nature than to devote time to academic studies. He was educated at Winchester and then at Balliol College, Oxford from where he left, discredited, with a third in jurisprudence (the philosophy of law). The life of a gentleman of leisure on his recently inherited estate of Fallodon in Northumberland beckoned but instead Edward developed what appears to be a sudden and unexpected interest in politics. His ancestry and contacts, not to mention a degree of skill as a public speaker, enabled him to quickly climb the political ladder as a valued member of the Liberal Party and in 1892 he was appointed Under Secretary for Foreign Affairs. Simultaneously though he seems to have retained and intensified his deep passion for the country life. An astute bird-watcher and expert on birdsong, he was more than an enthusiastic amateur. In 1893 he was one of the earliest members of the RSPB and became its vice-president in 1895. In 1898 he wrote a well-received book called Fly-Fishing and was a friend of one of the most celebrated nature writers of the time, W.H.Hudson (A Shepherd’s Life – now reissued on Little Toller). Later in life he published a book that is considered a classic of its kind, The Charm Of Birds, in which he writes on 125 different species of British bird, all from personal knowledge. Even before entering politics he had collected seventeen different species of water fowl on his Fallodon estate and when he found himself based in London he would first spend every weekend possible fishing at Brockenhurst in the New Forest before building his rustic bolt-hole on the Itchen in 1890. He was obviously a man with a deep affinity and love for a very enlightened version of rural life but at the same time found himself at the fulcrum of one of the most turbulent few years of British political history. Having just had to try and deal with the escalating ‘Irish problem’, July 1914 saw Sir Edward Grey, a foreign secretary so retiring that he only ever travelled abroad once – to France, entangled in a slowly unravelling diplomatic nightmare as Europe’s leaders sleepwalked their way to war. According to some revisionist historians Grey’s reluctance or inability to convince Germany at a crucial stage in the post-Franz Ferdinand assassination crisis that Britain would definitely be obliged to side with France should they, the Germans, invade France via Belgium, was tantamount to actually encouraging the Germans to advance their war plans to a point that made a pan-European conflict inevitable.

So was a day-dreaming, peaceful lover of nature, a man that seemed to care more about waterfowl and warblers than what was going on in the Balkans, a man who I would suggest embodies the very ethos that flows through the many tributaries of Caught by the River, was this man responsible for our participation in the horrors of 1914-18? I’ve read more than my share of First World War history books and I’m still not sure. But I hope not. A man who was so obviously good at heart, who appreciated the wonders of the natural world that we strive to maintain today, who was undisputed British ‘real tennis’ champion in 1896 for heavens sake, twice married (his first wife Dorothy died in an accident weeks after he took up the post of foreign secretary), parliamentary representative for Northumberland for over thirty years, British ambassador to the U.S…..a man like that deserves a more charitable place in history.

N.B.

The Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology at Oxford University is an academic body which conducts research in ornithology and the general field of evolutionary ecology and conservation biology.

A recommended biography – Edwardian Requiem : A Life of Sir Edward Grey by Michael Waterhouse was published recently.

More from Andy Childs on Caught by the River here