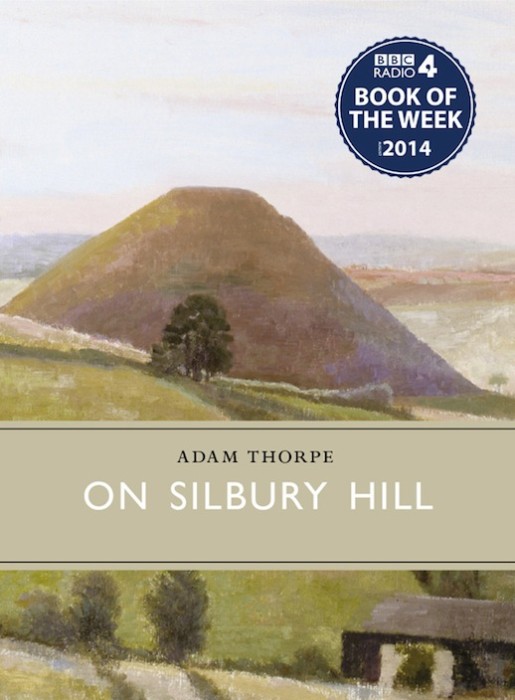

On Silbury Hill; Adam Thorpe

232 pages, hardback. Out now.

Review by Ben Myers

When it comes to the Neolithic antiquities that litter this island of ours – those stony secrets buried beneath the fetid top-soil – we keep returning to the same enduring question when confronted with this sentient mysteries: not always who or how or even when but why? Why is this here?

The standing stones of Stonehenge may capture international imaginations and provide easy access for passing tourists eager to tick the latest European stop-off from the list but any stone circle wandered or ley line diviner knows, Avebury and nearby Silbury Hill offer perhaps the more intriguing spectacle in the country. Why? is the invisible word writ large across its smooth, steep slopes. Why would anyone spend an estimated 18,000,000 man hours shifting 250,000 cubic metres of chalk over several decades to create the largest man made hill in Europe, a conical mound once bald and chalk-white, 130 feet (or 13 storeys) tall, a construction so impressive that “if the Titanic sailed just behind her in your dream, you would only see the smoke from the funnels”? Why, we wonder as we flock to it and point like primitives confronted with their first sighting of a comet. Why is it here?

Just as cynics react to modern art and sculpture with this same unanswerable question so centuries of English society and millions of visitors have tried to understand the reason for Silbury’s creation. It is as if the answer holds a deeper truth and understanding of ourselves. ‘There has to be a reason’ sits deep in the subconscious of all who tramp around its fenced-off perimeter and the fact we may never know makes Silbury such an enthralling landmark and immoveable part of the rural British psyche.

In a book that combines historical fact with memoir and poetry, Adam Thorpe answers this over-riding question in his opening line: “The point about Silbury Hill is she has no point.” With that out of the way he is free to combine fact with speculation, memory with emotion. Perhaps, he wonders, it was a memorial, a burial mound or a sculpture of Mother Earth erected to honour the soil fertility. Or maybe it was none of these. Certainly it has housed wooden Roman and Saxon hill forts at various points. We know that it has been excavated several times, most famously during a live TV broadcast in the 1960s. And it has almost certainly been a destination point for over four millennia for young courting couples (confession time: possessed by the spirit of the place, and the rules and regulations of 21st century living suddenly seemingly over-bearing, short-sighted and restrictive, myself and my partner felt an overwhelming urge to commune with our ancestors by sneaking through the fence and illegally – and possibly foolishly – climbing the mound for a tryst one warm summer’s evening.)

For Thorpe, who has written so well about changing rural English life in novels including Ulverton and Hodd, Silbury is “a hill of memories…a fragile museum exhibit; all she lacks is a glass case.” His response, like all the best nature and landscape writing, is entirely personal. He writes most movingly about his time as a slightly shell-shocked new arrival pupil at nearby Marlborough, where within seconds of his parents’ departure, a leg shot out to send him sprawling. The leg belonged to one Hawks-Gibbet: “And don’t you forget it”.

Thorpe’s Marlborough is one that has been inhabited by pupils who had already boarded for years before him; boys already institutionalised: “They knew the codes, and had grown inured to a lack of affection. They had, in a way, gone tribal – without the blood kinship of a true tribe.” When the death of a close friend who slid tragically and slowly down an ice shelf then six hundred feet to his death during an Outward Bound trip to Snowdon is announced in assembly and Thorpe witnesses some of his contemporaries giggling, and one even “in paroxysm of glee”, he finds himself trapped in “a House of Horrors that “has left me with a residue, not just of grief, but of fear – fear of my fellow human beings. That human beings can, given the right circumstances – an absence of love, say – entirely lack compassion, or feeling”. (Such recollections remind us just how close to reality Lindsay Anderson’s portrayal of a similar school in If… really was).

Meanwhile, as if to heighten the sensation of entrapment and isolation, outside the cold Victorian stone walls of a building which, like a prison, runs on its own routines, jargon and hierarchical power struggles, lies some of the most remarkable and intriguing landscape in the world – the gently undulating hills and chalk downs of Wiltshire. A place littered with Neolithic monuments, barrows and burial mounds. Naturally, Thorpe’s induction to this new countryside is via an exhausting thirty mile hike, which ends with him having to walk laps around the school running track as punishment for taking a short-cut across a field.

But in time, the countryside provides solace, as he adopts “a Shropshire Lad solitariness, a roaming freedom.” Cutting through copses or sitting in spinney, his young personality begins to form, increasingly defined through a love of landscape, animals, trees and clean skies. That Thorpe is within nine square miles that contain an embarrassment of historic riches – “Avebury henge, the Sanctuary, the two great Avenues, East and West Kennet Long Barrow, Windmill hill, the Marlborough Mound and various barrow cemeteries” – evidently helps in his development and, in fact his mental survival of school and then out into the wider world and all that the adult world reveals to him. But always at the symbolic centre sits the sublime enigma of Silbury mound.

Thorpe is sensitive and thoughtful as he out-lines the life – and always referred to in the feminine, Silbury does appear to be a living entity – of the hill. All impressive detective-work and field research aside, On Silbury Hill is a fine stand-alone memoir. But it’s more than that. It is a love letter, a homage to an object, a place and a symbol that has provided succour and mystery and hope and wonder – and will long continue to do so.

This weeks BBC R4 Book of the Week, On Silbury Hill, is published by Little Toller. Copies are on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £15.00