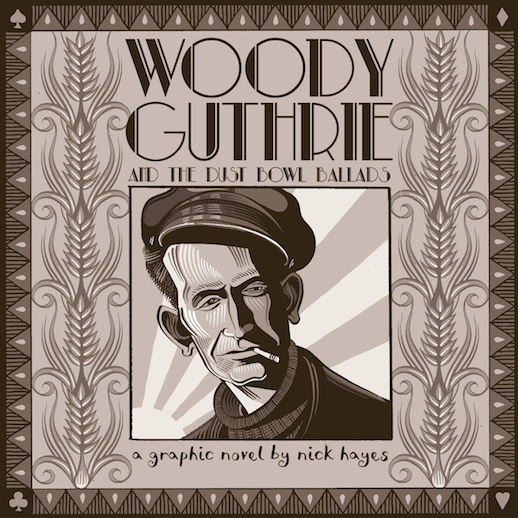

A Graphic Novel by Nick Hayes (Jonathan Cape)

Reviewed by Robert Macfarlane

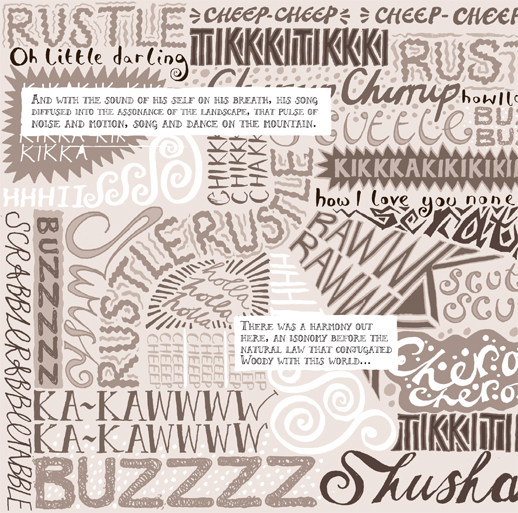

Rikkittytikkityrikkitytikkityrikkitytikk…!A strange sound starts this extraordinary book. The war-cry of a mongoose? A coin trapped in a tumble-dryer? Nope – it’s the noise of a kid halfway up a garbage heap, tapping out a rhythm on an upturned oilcan with a pair of spoons, somewhere in deep Oklahoma, sometime in the late 1920s.

The kid, of course, is Woody Guthrie, and he can’t keep music out of his head or his life, despite the extreme difficulties of his childhood: his mother sliding into dementia and violence, then being committed to the Oklahoma Hospital for the Insane; his father a Klansman involved in the lynching of two African Americans, Laura and L.D. Nelson, hanged by long ropes from a girder-bridge over the North Canadian River in 1911.

At 14, Woody was practically orphaned (mother committed, father lit out for Texas). He dropped out of school, ghosted around town, begged meals, learned the harmonica, memorized folk-songs and ballads, and busked for coins. How this washed-up kid with no foreseeable future would become America’s most influential folk-singer (his guitar famously stickered with ‘This Machine Kills Fascists’) is the subject of Nick Hayes’s Dust Bowl Ballads, a ‘graphic novel’, which is also a ‘fictionalised visual biography’, which is also a long lyric song to creativity, radicalism and the power of protest, and through which surges a moral force clearly inspired by Guthrie himself.

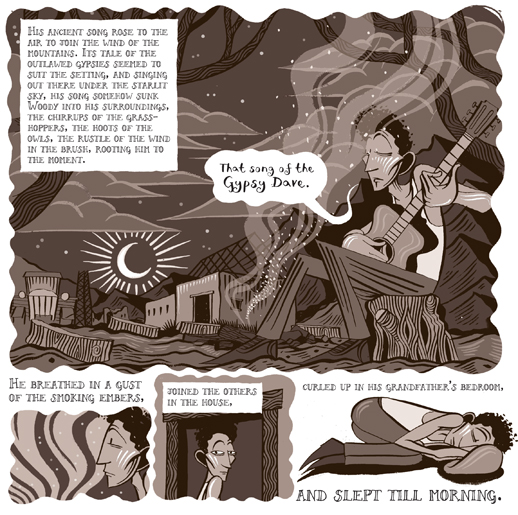

Hayes’s first book, published when he was 28, was The Rime of the Modern Mariner (2011: reviewed on this site here), a re-imagining of Coleridge’s visionary poem for our broken age of trash gyres, fish-stock collapse and reef-bleach.* It was an astonishing debut, partly for the boldness with which it rewrote STC, partly for the rhythm of its poetry, but above all for its dazzling visual idiom. Blues and marine-greens were the palette; there were hints of Hokusai in the curls and whorls that formed sea-foam, wind currents and human hair, shades of Gustave Doré in the anguished poses of the Mariner and his men, and echoes of Thomas Bewick’s chisel in the strong black pen-lines that led the reader’s sight.

But the style was, as the title promised, ‘modern’: no plangent pastoralism or throwback woodcut here. I was reminded most strongly, in fact, of the work of our greatest living writer-artist, Alasdair Gray: there in the political passion, impish wit, Blakean ritualism, and fascination with the body in all its aspects (dangling willies and clacking tongues, as well as flexed muscles and gazing eyes). How can anyone draw so much, so brilliantly, so variously? I wondered as I turned page after page of that book (lovingly published by Jonathan Cape).

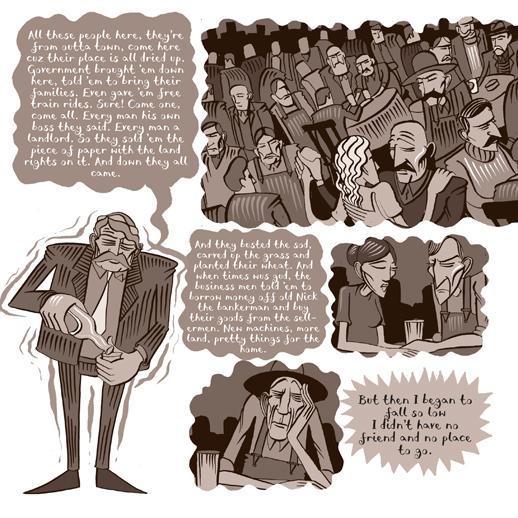

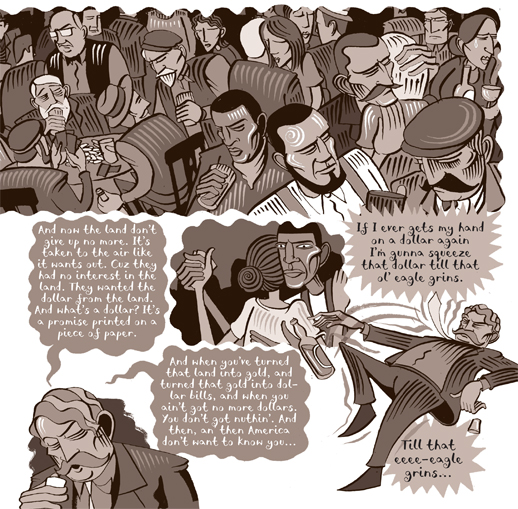

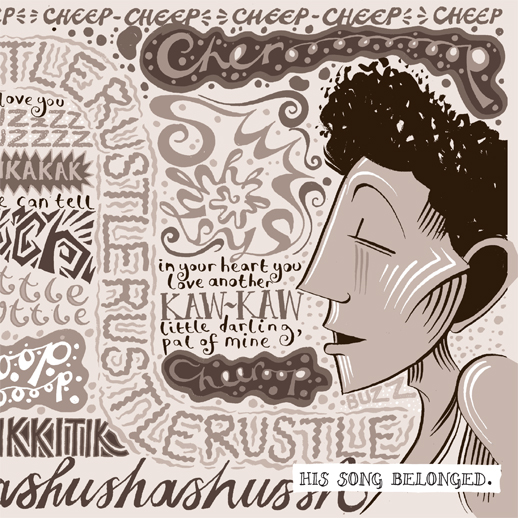

From water to soil, from spray to dust, and from blues to beiges: The Dust Bowl Ballads takes grim-black and grit-brown as its colour scheme, the hues of hardscrabble America. The leitmotifs are different, too: instead of the curl, the cross-hatch recurs – there in the steel struts of oil derricks, the mesh of chain-link fences, or the cracked earth of drought-struck farmland. But Hayes’s breathtaking visual inventiveness remains. He just can’t stay still as an artist. He does panels, I suppose, in the conventional manner of a ‘graphic novel’, but they constitute only a loose grammar. His images are frequently breaking out of their black boxes, spilling into margins and across pages, crossing boundaries and hopping fences, and otherwise performing versions of the kinds of trespass that Guthrie advocated in surely his best-known song, ‘This Land Is Your Land’:

As I went walking, I saw a sign there

And on the sign there, it said ‘no trespassing’.

But on the other side, it didn’t say nothing!

That side was made for you and me.

Guthrie inspires the lawlessness of the image-making; he also lends his lyricism to Hayes’s text, which you realise from page one is going to be its own kind of poetry, pitched somewhere between rap-battle and folk ballad (‘school’s crammed, gang’s rammed, there’s more boom than room in this ol’ town’; ‘the grit-grained grease-stained creased faces of the lumbermen, setting up shop, importing the supplies’).

I ended The Dust Bowl Ballads, much as I ended The Rime of the Modern Mariner, awed at the range and intensity of its achievement. Hayes seems to have designed and authored everything: he’s re-inked the Cape colophon, handwritten the front-matter and end-matter, devised his own font in which to letter the book, invented a prairieland-meets-William-Morris corn-ear pattern for the endpapers…and drawn more than a thousand separate illustrations. It’s a book you want to hold in the hand, but also to read aloud, to ‘sing it, swing to it, yodel it’ (to borrow from Guthrie). You finish it looking for an empty oil-can, searching for a pair of spoons, wanting to clatter out a rhythm of life, joy and hope ¬–– Rikkittytikkityrikkitytikkityrikkitytikk…!

*(Sharp-eyed readers of that book may have noticed that when in Section Seven the Mariner comes ashore after his near-drowning, his rebirth as a Green Man occurs first in a David Nash-inspired ash-tree bower, and then at a timber-framed house that closely resembles Roger Deakin’s Walnut Tree Farm).

You can pick up a copy from the Caught by the River shop here