image taken from the Robert Wyatt and stuff blog.

image taken from the Robert Wyatt and stuff blog.

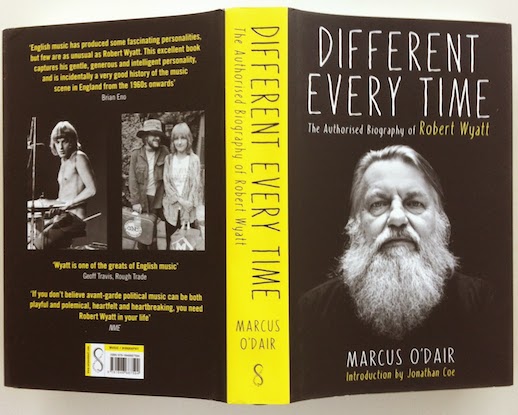

Marcus O’Dair; Different Every Time: the authorised biography of Robert Wyatt

432 pages, Serpent’s Tail. Out now

Different Every Time: Ex Machina / Benign Dictatorships (Domino)

Review by Rob St. John

Robert Wyatt is a national treasure; an inspiration; a true one off. In this, his first authorised biography, Marcus O’Dair – a popular music lecturer and musician in Grasscut – charts Wyatt’s unique life, drawing from lengthy interviews with Robert and his wife Alfie (who it seems, is a saint, and worthy of her own biography), and many of his friends and collaborators. Wyatt’s upbringing was bohemian and pastoral – his mother a BBC producer and his father a psychologist (who would eventually become confined to a wheelchair by MS – “It is very odd”, Wyatt says of how his fate echoed his father’s in this way). Wyatt learnt to play drums in a shed in Robert Graves’s garden on Mallorca, and applied his love of freeform jazz – inherited from his father – to making music with The Wilde Flowers, and then with Daevid Allen and Kevin Ayers as Soft Machine. Borrowing the band’s name from a Burroughs novel, Soft Machine’s first couple of albums are a freewheeling joy, drawing elements of free jazz and British psychedelia, with Wyatt’s half-spoken, seemingly-frivolous vocals wandering through it all: the topless singing drummer with a tux drawn on his chest in crayon, and a Pataphysical spiral etched into his bass drum.

His time with the Soft Machine would last until their fourth album, when the increasingly technical and po-faced band dispensed of his services, a split that would leave Wyatt hurt – as bassist Hugh Hopper put it, “We couldn’t stand him, and he couldn’t stand us”. Wyatt would subsequently form Matching Mole (a pun on Machine Molle – the French for Soft Machine) – a trademark Wyatt response, facing hardship with a pun and a smile; making some light of the situation.

In 1973 Wyatt fell out of a fourth floor window whilst at a party in London. Recalling the fall, in which he lost the use of his legs, Wyatt notes hearing a wolf’s howl in the distance. He would later be told that the howl was his own. During his recovery, Wyatt worked out new songs on the piano in the hospital visiting room, which would become 1974’s Rock Bottom. The day that record was released, Robert and Alfie married – ‘year zero’ as Wyatt terms it, where his new life would take shape.

From 1973 onward (‘Side Two’ in the biography), Wyatt adapted to his lot: his music making becoming a more solo enterprise, drawing in collaborators for individual songs played on his trademark Riviera organ, the ‘muddy mouth’ trumpet (the wordless, melodic refrains which began in the Soft Machine and can be heard in full flow on ‘Sea Song’), and latterly the cornet and trumpet. His songwriting was slow and steady – often in collaboration with Alfie, who also designed his album covers – but increasingly reliant on booze. Wyatt’s weirdness has always been fuelled (substance-wise) only by alcohol – a dependency which contributed to his 1973 fall, and one that he has only recently cast off.

For Brian Eno, Wyatt’s music has always been a British counterpoint to American country music, “When he sings about [the closeness of his relationship to Alfie], it’s as a grown-up complex relationship. Not like: ‘Ga-ga, I’m in love.’ It’s more like: ‘The two of us have stuck with each other, which is lucky as we get on quite well.” Wyatt’s social commentary would span the personal and political – particularly after he joined the Communist Party in the 1979. His series of singles for Rough Trade in the 1980s – At Last I Am Free (a straight-faced Chic cover), Stalin Wasn’t Stallin’, and the peerless Shipbuilding – are products of this political mileu, all fiery and full of feeling. Yet, prone to stage fright and nerves, Wyatt hasn’t played a solo gig since 1974.

O’Dair’s writing has an cool-headed academic rigour, with few of the vicarious cliches of many rock biopics, piecing together an engaging narrative from interviews with David Gilmour, Geoff Travis, Brian Eno, Jerry Dammers, Paul Weller, Björk and Hot Chip amongst many others. You can only imagine that the process of interviewing (although you get the impression the process was nothing as formal as the term implies) Wyatt and Alfie themselves must have been an enjoyable experience. There are anecdotes and tales on every page – some sad (describing Wyatt’s depression, insomnia and heavy drinking); many heartwarming or funny.

Shortly after curating the 2001 Meltdown Festival at the Southbank Centre – bringing together Terry Riley, Ivor Cutler and David Gilmour amongst others – Wyatt and Alfie went to see the Isreali jazz saxophonist Gilad Atzmon in Cleethorpes. Wyatt, intending to ask Atzmon to play on his next record, lost his nerve and sent up Alfie to talk to him instead. When introduced, Wyatt asked, “I’m an amateur musician, but I really like you and I would like you to record on my music”. You get the feeling this isn’t false modesty. Similarly, there’s something fantastic about the idea of Björk visiting Louth in Lincolnshire – where Wyatt and Alfie have lived since they left London in the mid 80s – to record, and Wyatt – this successful, veteran recording artist – getting so nervous that he would ask her to leave the house during his takes.

Different Every Time is illustrated with many photographs of Wyatt’s life: sketching with his parents on a London bombsite; in the early 60s, flicking through vinyl with a pencil moustache and rollie in hand; with Jimi Hendrix and at the UFO Club; and in front of a star and sickle selling the Morning Star outside a supermarket in Twickenham amongst many others. In many of these, Wyatt is smiling – beaming, even – a disarming, warm presence even when framed in black and white.

The Robert Wyatt that emerges from O’Dair’s words is someone who has maintained a singular vision throughout his career – even whilst embracing a diversity of approaches and sounds – someone who is championed both by the Wire / Cafe Oto crowd as much as he is by the mainstream. Indeed, it’s hard to find anyone who has a bad word to say about him. Close to the end of the book, O’Dair writes, “Of those that remain, many of Wyatt’s contemporaries have either turned into rock dinosaurs or made embarrassing attempts to remain hip. Robert has done neither. He still sings almost as he did in the Wilde Flowers [his pre-Soft Machine band], yet he has remained protean, permeable, so determined not to become a grumpy old man that he has turned into a kind of anti-curmudgeon: the Yesterday Man who worked with Björk and Hot Chip, the Cecil Taylor fan who loves Hear’Say.” In many ways it’s hard to write comprehensively about this excellent book, given Wyatt has led such a rich, productive and often troubled life that has been sympathetically documented and enlivened by O’Dair.

To mark the books release, O’Dair and Wyatt have compiled a two-disc compilation for Domino, covering most stages of his diverse career, along with his collaborations and guest appearances on tracks by Hot Chip, Nick Mason, Björk and John Cage. The 19-odd minutes of ‘Moon in June’ on the first disc ‘Ex Machina’ is a stunning, shapeshifting tangle of a song, as Wyatt sings ‘I wish I was home again’, in one of the final (and finest) moments of the Soft Machine, who were at that point shedding Wyatt’s song-based sensibilities. ‘Free Will and Testament’ from 1994’s Shleep is one of my favourite Wyatt moments, with lyricism amongst his most beguilingly affective: “So when I say that I know me, how can I know that? What kind of spider understands arachnophobia?”.

Disc Two, ‘Benign Dictatorships’ is more hit and miss (naturally, perhaps). Hot Chip’s ‘We’re Looking For a Lot of Love’ is amongst the best, with Alexis Taylor’s vocals – at once seemingly plain yet full of emotion and nuance – dovetailing neatly into Wyatt’s, sharing a similar idiosyncratic Britishness. ‘Shipbuilding’ – written for Wyatt by Elvis Costello and Clive Langer – is as strongly felt and subtly ornamented as ever. The final track on the second disc ‘Experiences No. 2’ by John Cage has Wyatt softly singing a few verses from e.e. cummings’ 1923 poem ‘Tulips and Chimneys’. Released on Brian Eno’s Obscure Label in 1976, the track is punctuated with electric silence – as Wyatt’s voice tails off into reverb – and his trademark wordless singing – part hummed reverie and part layered ‘muddy mouth’ trumpet. This is Wyatt unadorned – in song as in person – unique and fantastic.

——————————————————————————————————————————–

Buy the book.

Buy the music.

An Evening with Robert Wyatt is taking place this Sunday,23 November, at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on London’s Southbank. Information and box office can be found here.