Today we’re posting the second part of our exclusive extract from Robert Macfarlane’s phenomenal new book Landmarks. As with yesterday’s post, Robert’s writing concerns the late, great (and somehow ever-present presence of) Roger Deakin.

——————————————————————————————————————————

© The literary estate of Roger Deakin

© The literary estate of Roger Deakin

For Roger Deakin was a woodsman as well as a wordsman and a water-man. ‘The woods and the water as two poles in nature,’ he scribbled in one of the dozens of Moleskine notebooks he filled and kept over the years: ‘The one ancient, cryptic, full of wisdom. The other the vitality of water. The wood and the wet … would be good for us to understand more thoroughly.’ Roger dedicated his writing life to improving our understanding of the woods and the water – the volatilities of the latter, and the patient engrainings of the former. After the demands that followed the success of Waterlog had ebbed, he began work on what was to become a life-absorbing and eventually unfinishable book about trees and wood. It was the natural next subject for him – an investigation of what Edward Thomas elected as the ‘fifth element’.

Trees grew through Roger’s life. His mother’s maiden name was Wood, the third of his father’s three Christian names was Greenwood, and his great-grandfather ran a timber yard in Walsall. Roger worked for Friends of the Earth on campaigns to protect rainforests, and he co-founded the charity Common Ground, which among its many good offices championed old orchards and the pomological diversity of British apple culture. The house in which he lived was named for the big walnut that flourished alongside it, and that in autumn thunked its green fruit down onto the orange pantiles of the farm and rattled the wrinkly tin of the barn roof. Walnut Tree Farm was surrounded by water and by trees, in hedges and copses, and as splendid singletons – walnut, mulberry, ash, willow. Roger planted wood, coppiced it, worked it, and he burnt it by the cord in the inglenook fireplace at the heart of the farm, which was itself timber-framed, its vast skeleton made of 323 beams of oak and sweet chestnut, some of them more than four centuries old, held and jointed together with pegs of ash. In total, around 300 trees were felled to make the house, and the result was a structure that was organic to the point of animate. Truly, it was a tree-house, and in big winds it would creak and shift, riding the gusts so that being inside the house felt like being in the belly of a whale, or in a forest in a gale. ‘I am a woodlander,’ he wrote once, ‘I have sap in my veins’ – and as such he was a waterlander too, for ‘a tree is itself a river of sap’.

Roger once sent me a list of the apple varieties in the orchards of Girton College in Cambridge. He read them out when we next met, dozens of them, each a story in miniature, making together a poem of pomes: King of the Pippins, Laxton’s Exquisite, American Mother, Dr Harvey, Peasgood’s Nonsuch, Scarlet Pimpernel, Northern Greening, Patricia and (my favourite) Norfolk Beefing. It was a celebration of diversity and language, and it represented, Roger said, only a fraction of the pomology recorded in the Herefordshire Pomona, the great chronicle of English apple varieties.

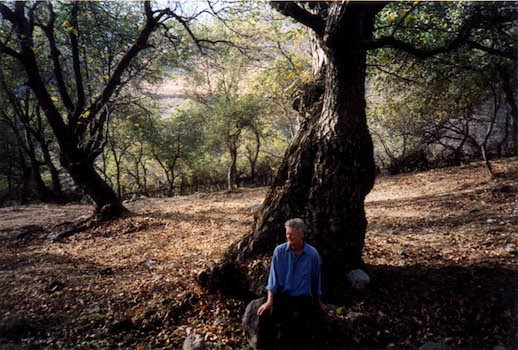

In the years he spent researching Wildwood, Roger travelled to Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, the Pyrenees, Greece, Ireland, Ukraine, Australia, North America and all over Britain and Ireland. He gathered a vast library of tree books, the pages of which he leaved with jotted-on Post-it notes. As it took root, the project also branched, digressing into studies of the hula-hoop craze, Roger’s anarchist great-uncle, the architecture of pine cones, the history of cricket bats and Jaguar dashboards, hippy communes, road protestors, the uses of driftwood… but returning always to individual trees and tree species.

Roger in the walnut forests of Kyrgyzstan © The literary estate of Roger Deakin

Roger in the walnut forests of Kyrgyzstan © The literary estate of Roger Deakin

This specifying impulse was distinctive of Roger’s approach. In September 1990 he gave a World Wildlife Fund lecture on education, literature and children at the Royal Festival Hall, in which he spoke passionately about the virtues of precision. ‘The central value of English in education has always been in its poetic approach,’ he said, ‘through the particular, the personal, the microscopic observation of all that surrounds us.’ It was attention to such particularity, he argued, that best permitted a Keatsian ‘taking part in the existence of things’, and ‘the development of this ability to take part in the existence of things’ was in turn ‘the common ground of English teaching and environmental education’. Roger ended the lecture with an attack on generalism as an enemy of wonder because it suppressed uniqueness. He quoted a passage from his beloved D. H. Lawrence in support of his argument:

The dandelion in full flower, a little sun bristling with sun-rays on the green earth, is a non-pareil, a nonsuch. Foolish, foolish, foolish to compare it to anything else on earth. It is itself incomparable and unique.

Foolish, foolish, foolish Lawrence, though, for even as he celebrates the ‘non-pareil’ and berates the comparative impulse, he cannot prevent himself figuring the dandelion as a ‘little sun’, so that it is itself and not-itself at once. But Lawrence, like Roger, would have defended the metaphor as an intensifier rather than a comparator – a means of evoking the dandelion-ness of that dandelion, instead of diffusing its singularity. Some of Roger’s most precise observations of natural events used figurative language to sharpen, rather than to blunt, their accuracy. When he writes that ‘[r]edstarts flew from tree to tree, taking the line a slack rope would take slung between them; economy in flight is what makes it graceful’, it is the aptness of the ‘slack rope’ that makes the observation itself graceful. Like Baker, he was unafraid of elaborate comparisons: the ‘park-bench green’ of a pheasant’s neck; a hornet ‘tubby, like a weekend footballer in a striped vest’.

In the spring of 2006 I drove over to Walnut Tree Farm with my friend Leo and my son Tom, then only a few months old. Leo and I swam in the moat, and we noticed that Roger did not join us. We hung our towels on the Aga rails, and Roger pressed our swimming trunks into waffle grills and dried them out over the hot plates, returning them to us crispy. Roger held Tom, and we talked about Wildwood. He seemed more distracted than usual, though, and quieter. I worried that I had upset him somehow. I wrote to him that night, apologizing for phantom faults.

Not long after that visit, and out of the blue, Roger was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumour. Its progress was bitterly swift. In early June, Roger called to ask if I would act as his literary executor. I said I would. It was a difficult conversation. His illness was seriously advanced. He was having trouble forming speech. I was having trouble not crying. He died soon afterwards. The coffin he lay in had a wreath of oak leaves on its lid. Just before it glided through the velvet curtains and into the cremating flames, Loudon Wainwright’s ‘The Swimming Song’ was played, full of hope and loss. It brought me to shuddering tears that day, and whenever it pops up now and then out of the thousand songs on my phone, it still stops me short like a punch to the chest.

Roger rarely threw anything away. He was an admirer of old age, and he lived in the same place for nearly forty years – so whenever he ran out of space to store things, he just built another shed, raised another barn, or hauled an old railway wagon or shepherd’s hut into a patch of field and began to fill that up with stuff too.

Roger’s shepherd’s hut in winter © The literary estate of Roger Deakin

Roger’s shepherd’s hut in winter © The literary estate of Roger Deakin

In the strange months after his funeral, it became clear that the main question facing me as his executor was what to do with all the language he had left behind: the hundreds of notebooks, letters, manuscripts, folders, box-files, cassettes, videotapes and journals in which he had so memorably recorded his life.

Six months after Roger’s death, Walnut Tree Farm passed into the ownership of two remarkable people, Titus and Jasmin Rowlandson, friends of Roger’s and now friends of mine. They moved into the farm with their two young daughters and began – slowly, respectfully – to make it their home. As they moved from room to room and barn to barn, so they found more of Roger’s papers, stashed in trunks and boxes, pushed under beds or shoved into sheds where the mice had made nests of his notes. They kept everything, storing it all in the attic room of a steep-eaved barn that Roger had raised in the early 1970s.

Four years after Roger’s death, I could no longer put off confronting his archive. I drove across to the farm on a warm early-summer day. Jasmin led me up one ladder to the first floor of the barn, then pointed up another that led through a flip-back trapdoor and into the narrow attic.

‘Up you go! Good luck. It’s going to take you a while …’

Dusty light fell from a gable window. The air was hot and musty. There was a single bed under the window, a clear aisle down the centre of the room leading to it, and otherwise the attic room was full, floor to slanted ceiling, of boxes and crates. Eighty? A hundred? I felt overwhelmed. How could this volume of documents ever be brought under control? I sat down on a box, took a notebook from the top of a crate and leafed through it. ‘Angels are the people we care for and who care for us,’ read the sentence at the top of one page, in Roger’s spidery black handwriting. There followed a jotted thought-stream on angels, which moved out to the double hammer-beam roof of the church in the fenland village of March – where the wings of the 200 wooden angels in the roof are feathered like those of marsh harriers – and then back again to further reflection on the nature of friendship.

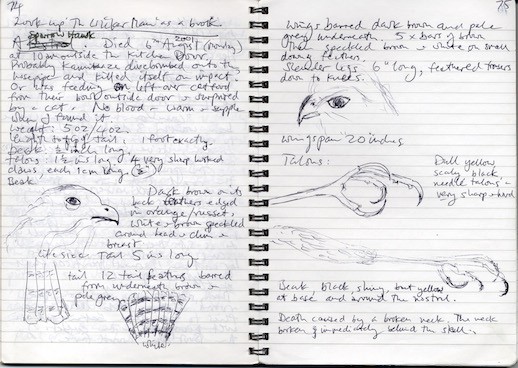

With Titus and Jasmin’s generous help, I began the process of working out what Roger had left behind. Digging through boxes; brushing away mouse droppings and spiders’ webs; scanning letters from friends and collaborators; putting letters from lovers and family to one side unread. Each box I opened held treasure or puzzles: early poems; first drafts of Waterlog; a copy of the screenplay for My Beautiful Laundrette sent to Roger by Hanif Kureishi; word-lists of place-language (tufa, bole, burr, ghyll); a folder entitled ‘Drowning (Coroners)’, which turned out not to be a record of coroners that Roger had drowned, but an account of his research into East Anglian deaths-by-water. It was hard not to get distracted, especially by his notebooks. Each was a small landscape through which it was possible to wander, and within which it was possible to get lost. One recorded his discovery of a dead sparrowhawk outside his kitchen door, which he suspected had killed itself as part of a ‘kamikaze divebomb’ attack.

© The literary estate of Roger Deakin

© The literary estate of Roger Deakin

Another carried a paragraph in which Roger imagined a possible structure for Wildwood: he compared it to a cabinet of wonders, a chest in which each drawer was made of a different timber and contained different remarkable objects and stories. The notebooks, taken together, represented an accidental epic poem of Roger’s life, or perhaps a dendrological cross-section of his mind. In their range and randomness, they reminded me that he was, as Les Murray once wrote, ‘only interested in everything’.

*

The last three boxes of Roger’s archive were found in 2013, in the dusty corner of a dusty shed. Jasmin called to let me know that more material had turned up; would I like to come and collect it? I drove over, had lunch, walked the fields with Titus and Jasmin and took the boxes home. That evening, kneeling on the floor of my study, I began to sort through the contents. There were files and notebooks from Roger’s schooldays, A4 notepads with scribbles and jottings, a new clutch of letters and pamphlets from the early years of Common Ground, and then, with a jolt of shock, I found a blue foolscap folder with a white label on the front, on which Roger had written ‘ROBERT MACFARLANE’.

I paused. I thought about throwing it away unopened. What if it held hurt for me? I opened it. It contained five letters. The letters weren’t about me – they were from me, to Roger, all written in 2002–3, when I was first coming to know him. Two were handwritten, two were typed, and one was the printout of an email. I had no memory of any of them, and for that reason I encountered my own voice almost as a stranger’s:

Tuesday 11 February 2003

It was great to get your letter, Roger, and to be transported out of my bunker-office in Cambridge, to the walnut woods of Kyrgyzstan. The word that really leaped out at me, oddly, from your description, was ‘holloway’ for the sunken lanes you saw. My wonderful editor is called Sara Holloway, and reading your letter, her name – which I have said often but never thought of as possessing an origin in the landscape – suddenly became rich with association and image. I could infer a meaning for it from your description, but wanted to know more, so went to my Shorter Oxford Dictionary. It wasn’t there, so I hauled out the complete OED, and discovered, buried in the small print of the ‘variants’ of meaning No. 7, the following: ‘hollow-way, a way, road or path, through a defile or cutting, also extended, as quot. in 1882).’ That was all, but it was enough. I wonder where you picked the term up from? What a word it is! It made me think of the description of a holloway – though he does not call it such – in Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne. A friend and I are fascinated by ways, paths, ancient roads, ley-lines, dumbles, cutting and – I now know – by holloways. So: thank you for the gift of the word.

Roger’s gift of that word would set further ripples of influence ringing outwards. Two years later he and I would travel together to the ‘holloways’ of south Dorset, in search of the hideout of the hero of Geoffrey Household’s cult 1939 novel, Rogue Male, who goes to ground in a sandstone-sided sunken lane in the Chideock Valley.

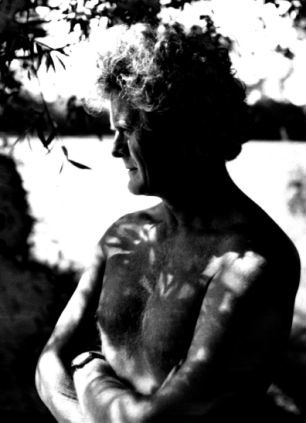

Roger in the meadow above the holloway, near North Chideock. © Robert Macfarlane

Roger in the meadow above the holloway, near North Chideock. © Robert Macfarlane

Seven years after that trip, I returned to Chideock with the artist Stanley Donwood and the writer Dan Richards, with whom I co-wrote a small book called Holloway – though by then I had fully forgotten the work’s true origin in that letter from Roger to me about the walnut woods of Kyrgyzstan and their deep-trodden lanes.

The other gift I received from Roger’s trip to Central Asia was an apple pip. He had travelled to the Talgar Valley in the mountains of Kazakhstan in search of the ur-apple – the wild apple, Malus sieversus, that was thought to have evolved into the domestic apple, Malus domesticus, and in that form found its way to Britain thanks to the Romans. On the northern slopes of the Tien Shan massif, Roger had filled three film canisters with wild-apple pips and damp cotton wool, and carried them home to Suffolk. He planted the pips in pots on his kitchen windowsill and there they had grown to seedlings. But then Roger died and the seedlings almost died with him, as the creepers on the outside of the farm grew untended over the kitchen window and shut out the sun. Potbound and sun-hungry, each seedling developed an obvious kink in its trunk from the months around Roger’s death, where they had leaned desperately lightwards.

Then Titus and Jasmin rescued them, re-potted them and gave them light. The seedlings flourished into saplings. When spring came, Titus planted out ten of the ur-apples in a field just behind the barn where Roger’s archive was kept, making an apple avenue. And Jasmin gave one of the saplings to me. I planted it in the chalky clay of my suburban garden, and to my surprise it flourished there.

It takes about twelve years for an apple tree to grow from pip to first fruiting. I write this in the spring of 2014, eleven years after Roger returned from Central Asia. My ur-apple flowers with white blossom, its leaves are a keen green, and it still has the sharp crook near the base of its trunk that remembers Roger’s death. Next year, all being well, it will fruit for the first time.

*

A life lived as variously as Roger’s, and evoked in writing as powerful as his, means that even after death his influence continues to flow outwards. Green Man-like, he appears in unexpected places, speaking in leaves. There is, of course, a tendency to hero-worship those who lived well and died too young, as Roger did. Laundry lists and emails become holy writ; hallowed places become sites of pilgrimage; admiration is expressed through ritual re-performance; and idealism threatens to occlude the actual. I know that Roger was no pure Poseidon or Herne: that he flew often and without apparent pangs to his conscience, that he could at times talk too much and at times too little, and that he was unrepeatably rude to any Jehovah’s Witnesses who made the long trudge down the track from Mellis Common to the front door of Walnut Tree Farm. But his writing did show people how to live both eccentrically and responsibly, and by both dwelling well and travelling wisely, he resolved in some measure the tension between what Edward Thomas called the desire to ‘go on and on over the earth’ and the desire ‘to settle for ever in one place’. Above all he embodied a spirit of childishness, in the best sense of the word: innocent of eye and at ease with wonder.

Though Roger is gone, many of his readers still feel a need to express their admiration for him, and the connection they felt with his work and world view, and so they still write letters, as if he might somehow read them. As I am Roger’s literary executor, and as our writings have become intertwined, many of these letters find their ways to me. They come from all over the world, and from various kinds of people: a professional surfer from Australia, a Canadian academic, a woman from Exeter confined to her house due to mobility problems, a young man re-swimming the route of Waterlog, lake by lake and river by river, in an attempt to recover from depression. Titus and Jasmin have to cope with the scores of Deakinites who come on pilgrimage to Mellis each year, wanting to see the farm and its fields. Most are polite. Some expect it all to have been kept as a shrine or museum, and are offended by the changes they perceive. Some, inspired by Roger’s insouciant attitude towards trespass, wander the fields uninvited, or take unannounced dips in the moat.

But all of the pilgrims, and all the letter writers, are under Roger’s influence, and as I know that feeling well I do not begrudge them it. Among the letters I have received, one of the most heartfelt came from a Dutch-English reader, and this is how it began:

I am Hansje, born and bred in the north Netherlands where I bathed from age one in lakes, river and cold-water outdoor pools. Here in Warwickshire, where I have lived for some thirty-three years, I am among other things a swimmer, and if you ever wish to swim in the beautiful Avon, then do tell me and I will show you to the best and secret places. I have never experienced the profound sense of loss of someone I have never met as when I learnt that Roger had died. Many sentences in each of his books are as if engraved in me, find a resting place, a recognition, they are magnifying glass, lens and microscope to the natural world, a watery surface through which I look to see the earth clarified.

© The literary estate of Roger Deakin

© The literary estate of Roger Deakin

——————————————————————————————————————————

Caught by the River would like to thank Robert and his publisher, Hamish Hamilton, for their generosity in allowing us to publish this chapter.

Landmarks can be bought from the Caught by the River shop, priced £15.

Robert will be reading from Landmarks at the Caught by the River Faber Social on 13 April. Information on this event can be found here.