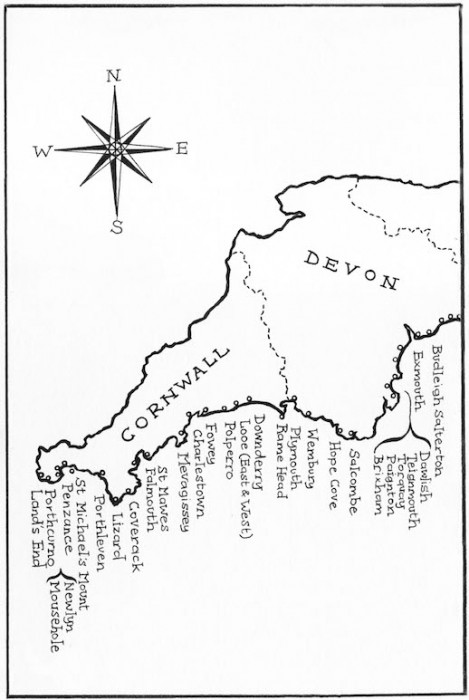

On this historically treacherous stretch of Cornish coastline, Tom Fort comes upon the blissful Kennack Sands. Taken from his forthcoming book Channel Shore: From the White Cliffs to Land’s End.

From the chapter Gabbro and Serpentine:

The lane out of the village led to another lane and then another, until I found myself crossing Main Dale, a wild tract of heather and gorse with lumps of gabbro scattered all around, and descending into Coverack. The sun had come out and the cove, its sand undefiled by quarry waste, looked distinctly picture-book. Flotillas of kayaks were scudding about and a handful of brave swimmers were breasting the waves. The village looked very neat, the slopes thickly covered with white-washed bungalows and villas. The village noticeboard advertised a range of wholesome activities – beach clean day, RNLI day, the Coverack regatta, the Coverack Singers performing Anything Goes, a sale of unframed pictures at the Arts Club.

A constant fear and intermittent menace along this whole coast in distant times were the predations of the Barbary pirates – often referred to in contemporary accounts as ‘Turks’ although they mostly came from North Africa. During the seventeenth century hundreds of fishing boats and other vessels were ambushed by the dreaded xebecs and galleys, and thousands of fishermen and seamen were captured and sold into slavery in Tunisia, Morocco and especially Algeria. Most were never seen again.

The chronicles of the village of St Keverne refer to repeated incidents of boats fishing off the Manacles being seized and emptied of their crews ‘to the sorrowful complaint and lamentable tears of their womenfolk’. Witnesses deposed that ‘these Turks daily show themselves… and the poor fishermen are fearful not only to go to sea but likewise lest these Turks should come on shore and take them out of their houses.’

They were right to be fearful. A petition smuggled from Algiers in 1640 and delivered to Charles I said there were five thousand English slaves in ‘miserable captivity undergoing most insufferable labours… suffering much hunger and many blows to their bare bodies by which cruelty many have been forced to turn Mohammedans.’ It’s estimated that between 1580 and 1680 as many as a million Europeans were enslaved in North Africa, the great majority from fishing communities too poor to pay ransoms. The slaving raids continued throughout the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth. In 1816 a naval force led, on his final command, by that great Cornishman Edward Pellew – by then ennobled as Lord Exmouth – put Algiers to flames and forced its Bey to renounce the enslavement of Christians.

* * *

Every slog has its champagne and foie gras – or ale and pork scratchings – moments. I had one when I first laid eyes on Kennack Sands. I had bumped down a long track to a farm, Trevenwith, with the sun in my face. The path went through the farmyard and down the side of two sloping meadows. I stopped at a gate where the path was squeezed between banks of hawthorn.

To the west the glittering sea was roughly edged by one headland after another. The Lizard was the last, shaped like a reptile’s head lain flat on the sea, its tongue the white foam breaking on the rocks. Long breakers rolled slowly against the twin hemispheres of Kennack Sands, divided by the Caerverracks, a broken jumble of black rocks reaching out into the sea. The sand was pale and ribbed, gently inclining into water so clear that every stone and dab of weed was visible. A gang of kids was messing around with body boards where the waves crashed down. Further out two or three more serious surfers bobbed about biding their time until a significant crest showed itself.

A band of heather, gorse and hawthorn, littered with pale, lichen-spotted rocks, stretched behind the beach, with green meadows beyond. Everything glowed in the sun, beneath a soft blue sky.

A slim, blonde woman in beach gear came up the path towards me. She was on her way back to Trevenwith, where she lived, leaving her sons and friends on the beach. I asked her about the farm. More of a smallholding, she said. They did beef cattle and some sheep, not enough to make a living, so she worked in Penzance for social services, helping ‘problem fam- ilies.’ There was no shortage of families or problems: generational unemployment, abundant drugs coming through the port at Newlyn, crime, hopelessness. She said it was the end-of-the-line syndrome. People just washed up in Penzance with no further to go.

‘Then I come back to this,’ she said looking back at Kennack Sands. ‘It’s a paradise. I’m so lucky.’

Coming out onto the beach my peripheral vision registered a change in the texture of the light to the west. I looked that way, initially puzzled as to why the fields should look different. Then I realised: it was the gleam off the roofs of caravans, massed ranks of them in wavering lines, crescents and triangular blocks across the downslope of the western flank of the valley. In all there are four holiday parks, shoulder to shoulder. A lane crept down from the nearest to a car park close to the beach. The car park was full and the lane was lined with cars. There was a café awash with families chomping and slurping. The sand was thickly peopled.

From the cafe I looked back to where the roof of Trevenwith Farm peeped above the trees. The fields behind were spotted with livestock, noses down in the rich grass. Paradise was a restricted area.

Channel Shore: From the White Cliffs to Land’s End is published in hardback by Simon & Schuster on May 11th. Pick up a copy for £12.99 in our shop.