Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties

by Elijah Wald

Dey St. 354pp hdbk. Out now

Review by Andy Childs

I have more than my fair share of books on Bob Dylan and have actually read most of them, but apart from Chronicles of course and perhaps Paul Williams’ books I don’t think I’ve enjoyed or been impressed by any of them as much as this one. Published to coincide with the 50th anniversary of an event that was undoubtedly a significant but myth-ridden moment in music history, namely Bob Dylan’s three-song ‘electric’ set at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, Dylan Goes Electric! is a masterful work of contextual analysis and as level-headed and accurate an account of the origins and aftermath of a seminal marker in folk/rock history as I’ve ever read.

Wald’s premise for this book, and one that is hinted at in its subtitle, is that to fully understand why Dylan’s appearance with an electric guitar and a band at Newport in 1965 has taken on such significance we need to examine the U.S. folk revival movement of the 50s and 60s, Pete Seeger’s background and crucial involvement in that movement, the history of the Newport Folk Festival, the emerging youth culture that needed to find a voice of its own, Bob Dylan’s career up to that point, the known facts about the event itself and the myths that have developed around it, and then the aftermath that energised a generation and that still resonates today. All of this Wald does, concisely and objectively, in ten chapters. It’s 257 pages before we get to the point where a black leather-jacketed Dylan takes the stage with an electric guitar and Paul Butterfield’s Blues Band behind him and launches into ‘Maggie’s Farm’, Mike Bloomfield’s searing solos punctuating Dylan’s every line, but by then we’re fully primed. We know what’s going to happen and we have a pretty good idea why.

Chapter one, ‘The House That Pete Built’, relates the early career of Pete Seeger and his crucial role in the emergence of the U.S. folk revival movement that began in the late 40s, grew in scope and popularity throughout the 50s and flourished with some considerable commercial success in the early 60s. It was a movement that encompassed and promoted ‘traditional’ folk music from around the world and was enshrined in socialist ideology, the concepts of freedom and the rights of man. It was an overwhelmingly worthy crusade both socially and musically but as it developed it fractured into cliques that bickered and argued bitterly about the way the music seemed to be side-tracked along the sort of commercial lines that compromised their virtuous ideals. No-one epitomised the dilemmas that folk music faced more than Pete Seeger who, on the one hand pioneered commercial pop-folk with his group the Weavers, and on the other hand “simultaneously parented its traditionalist opponents”. As such he is the crucial figure in this part of the story, the man that everyone respected and looked for for guidance. Folk’s godfather.

Nothing of consequence apparently happened in the world of folk music without Seeger’s involvement, including the Newport Folk Festival which first made its appearance as a ‘folk music afternoon’ during the 1959 Newport Jazz Festival, already five years old. Pete Seeger, Odetta, and the Kingston Trio played and they were an instant success. The following year there was a three-day folk event and the Folk Festival proper was up-and-running with Pete Seeger and his dual vision of traditional ethnic music living not altogether harmoniously side-by-side with increasingly anodyne pop-folk, at the helm aided and abetted by the likes of Theodore Bikel, Jean Ritchie, Erik Darling, Peter Yarrow and later, Alan Lomax.

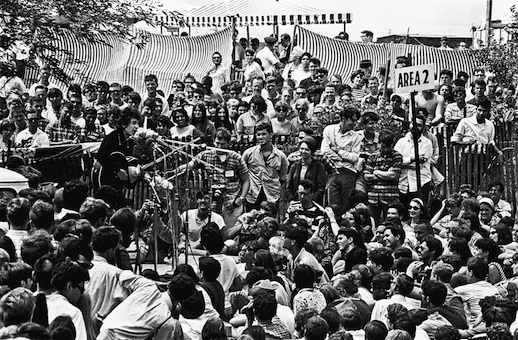

Meanwhile, in 1961, Bob Dylan had arrived, with his Woody Guthrie fixation, in New York and proceeded to make a name for himself in the bars and clubs of Greenwich Village. I can’t think of a better guide to that period of music history than Wald and his chapters on Dylan’s early days in Minnesota, his progression as a performer and songwriter in New York, his ratification as a folk music icon and his eventual emergence as a completely individual poet/visionary/performer make riveting reading. Perhaps the most contrasting years in Dylan’s early development were between 1963 and 1965 and this is clearly evident in Murray Lerner’s marvellous documentary film The Other Side of The Mirror which focuses exclusively and without commentary on Dylan’s performances at the ’63, ’64 and ’65 Newport Folk Festivals. The difference in him in those two years is remarkable. In ’63 he was still essentially a rough-around-the-edges folky, by ’64 he was a star in that particular firmament – and he knew it, and by ’65 he was brash, confident, even arrogant, had a repertoire of original material that no-one else could match, and was ready to break free and blow up a storm.

Besides portraying the complexities of the leading characters, the important developments, and the growing fissures that dominated the folk music world, Wald also discusses the various wider social and musical changes that were taking place in the U.S. in the early sixties – political activism, youth’s aspiration to rid themselves of the legacy of the staid, conservative, black and white 50s, and the birth of what came to be known as ‘rock music’. This emerging energy, this restless new culture needed a spokesman to articulate and romanticise their ideals and Dylan, an obviously huge talent, with entirely the right attitude, was in the right place, at exactly the right time. Undoubtedly encouraged by his controversial manager Albert Grossman, he seized the moment to declare his independence and elevation and made the most startling statement of intent at a venue guaranteed to cause the most controversy.

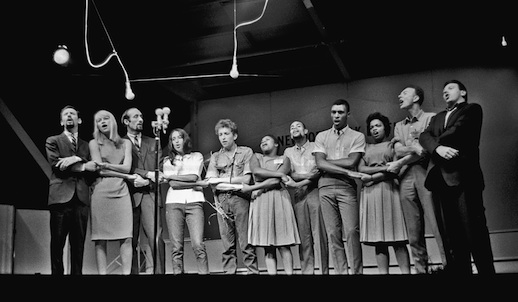

Newport 1965 Richard and Mimi Farina with Al Kooper and Bruce Langhorne. Photo: Robert and Jerry Corwin

Newport 1965 Richard and Mimi Farina with Al Kooper and Bruce Langhorne. Photo: Robert and Jerry Corwin

Dylan ‘going electric’ in 1965 at Newport wasn’t actually a total shock musically though – ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ featuring Mike Bloomfield on electric guitar and Al Kooper on keyboards had been released as a single in the months beforehand and by then everyone knew which way the wind was blowing. The furore at Newport in 1965 was less about what and how Dylan played and more about the crowd’s reaction and, more significantly, about the reaction of Pete Seeger (and to a lesser extent Alan Lomax). And this is where the myths emanate from and where the story becomes mired in heresay. Without for one minute diluting the impact that Dylan made that day, Wald does an admirable job of trying to unravel truth from fiction. Dylan and band played just three numbers altogether – ‘Maggie’s Farm’, ‘Like A Rolling Stone’, and a somewhat shambolic rendition of a song that later became ‘It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry’. The audience reaction was decidedly mixed. The Dylan fans (and their presence in numbers at the festival were a cause of concern for traditionalists who despised celebrity culture) cheered and applauded, the older, betrayed folkies booed, and everyone else gasped in disbelief at what was seen as sacrilege by some and a thrilling glimpse of the future by others. You can hear it all clearly in Murray Lerner’s film. Dylan himself looked composed and confident and not at all flustered or even tearful at the crowd’s reaction as some reports had it. Although the sound quality was another oft-repeated cause for complaint, to my ears the sound they made was the very definition of ragged glory, and ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ especially remains a prolonged hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck moment. It doesn’t seem particularly loud now but then, in an age before gigantic stacks of stadium speakers and at a folk festival for heavens sake, it must have been deafening. Pete Seeger certainly thought so and the excessive volume seemed to be his main gripe. Joe Boyd recounts the scene amusingly in his White Bicycles memoir. Ubiquitous Joe was stage manager at the festival and while Dylan played and an apoplectic Seeger ran around backstage with his hands over his ears and his wife in tears (but not, as fanciful legend has it, wielding an axe) he was told by Lomax, Seeger and Bikel to go to the mixing desk, guarded by Grossman, Yarrow and Paul Rothchild and get the sound turned down. Their response was unsurprising and Joe returned with politely modified message of “fuck you!”. The new guard had superceded the old. As one scribe put it at the time “Dylan electrified one half of the audience and eletrocuted the other”. The traditionalists were outraged. “You don’t whistle in church – you don’t play rock and roll at a folk festival” whined Bikel. The rowdy gatecrashers in the church of folk were triumphant. As Wald says : “it was not news that Dylan was the future; the news was that Seeger was the past”. In a move that was possibly designed to placate the bewildered and angry in the crowd, Dylan returned to the stage with an acoustic guitar and played a superb ‘Mr.Tambourine Man’ and ‘It’s All Over Now Baby Blue’ before exiting leaving Pete Yarrow to try and introduce the unfortunate act billed to follow all that – the Moving Star Hall Singers – to an audience who were either deflated, stunned or energised.

Whether the subsequent fall-out and aftermath threw the folk world into prolonged self-examination is almost a subject for another book but it did, for better or worse, kick-start the revolution that saw rock music inherit from folk the mantle of the music of protest, of rebellion, of youth and of the future. And Bob Dylan was leading the way.

Elijah Wald is a very fine writer – his prose has rhythm and clarity backed up by solid research and sound opinions. His book on Dave Van Ronk – The Mayor of MacDougal Street – is required reading for a full understanding of the development of the Greenwich Village folk scene of the 50s and 60s and serves as a useful companion to this one. That he has managed to pack so much information into little over 300 pages and in a way that brings that era to life so vividly and puts you at the centre of the action is a small miracle. If you only ever read one other Bob Dylan book ever again make it this one.

Dylan Goes Electric can be bought from the Caught by the River shop at the special price of £15.00

Andy Childs on Caught by the River