Nextinction by Ralph Steadman and Ceri Levy.

Bloomsbury. Hardback, 224 pages, £35.00. Out now.

Review by Ben Myers

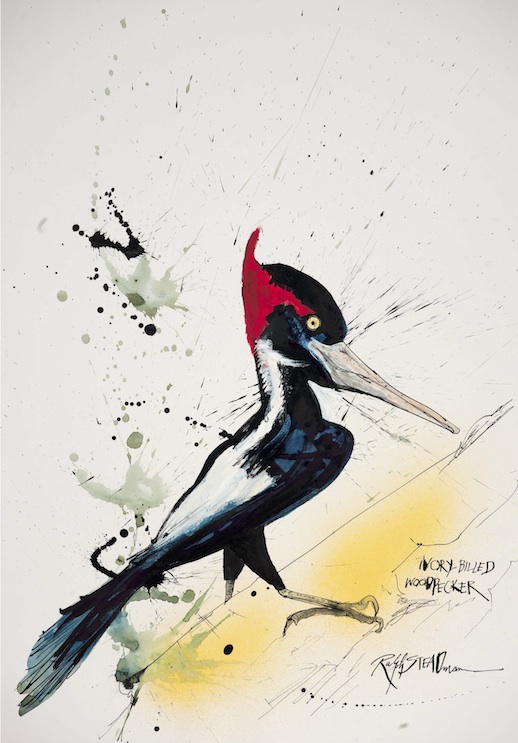

Try to describe Ralph Steadman’s influential and instantly recognisable style in one simple word and you may well come up with “life”. For over fifty years his artwork has burst forth with a frenzied kinetic energy that is the essence of life itself. A Steadman image pulses with blood and ejaculates bodily fluids; it is a frozen moment that assaults the senses, the closest that a static painting can come to representing true movement, and a direct challenge to any frames, pages, books or billboards to attempt to contain it. His is a style that has taken work by creators as disparate as Ted Hughes, George Orwell, Hunter S Thompson, Lewis Carroll, Flann O’Brien and Frank Zappa and cranked it up to new levels of ocular mayhem. Steadman combines humour with energy to amplify life in all its glorious forms.

It seems fitting then that Nextinction is a homage to and documentation of those birds who tread the tightrope between life and death – those on the cusp of being forever obliterated from existence by humanity’s multitude of vulgar sins (agriculture, deforestation, urbanisation, climate change) and our insatiable appetite to tame, maim, mount, own, crush, pluck, stuff, eat, colonise and just generally impose ourselves like a particularly self-centred unwashed commuter manspreading his legs wide across an airless carriage. For, invasive species aside, it is man that is doing all the killing: 140 species of birds have disappeared in the past five hundred years. A staggering one in eight of the planet’s birds are currently threatened with extinction, 213 species critically endangered. They could be gone in twenty summers.

A collaboration with film-maker, writer and Caught by the River contributor Ceri Levy, who offers “a wing and prayer commentary” to Steadman’s voluminous paintings, Nextinction continues the garrulous pair’s collaboration, which began with their 2012 collection Extinct Boids, a collection of works about such dear departed avian friends as are already famous for all the wrong reasons – Great Auk, Passenger Pigeon and Dodo, and several entirely fabricated Steadman surprises such as the Blue Slut, the Gob Swallow and, of course, the Needless Smut thrown in for good measure. Collectively they answer the question of how to tackle such a subject as the demise of a species: with humour, of course. Humour disarms the idiots, makes the terminally grim palatable and, on a deeper level, can usher in real change.

And that, perhaps is Nextinction’s true purpose: to remind us of the rarity of these critically endangered birds and the absurdity of a world that places obscene value in gaudy trinkets, but close to zero in creatures more beautiful than anything mined or melted, stitched or painted.

Steadman and Levy’s approach is as free-wheeling as you might suspect, the former’s paintings accompanied by the latter’s observational biographies that are by turns informative and fanciful, and all collated with a running commentary from the two hosts via diary entries, email exchanges, conversational transcriptions, notebook jottings and wordy, poetic interplay that is as energised as the portraits of the birds themselves. There is generous use of the screamer, each “!!!” issued like a well-aimed, wrist-flicking ink-splash from Steadman’s brush.

Throughout, the lines between fact and fiction, truth and lie, bird and boid are continually blurred – almost to disarming, disorientating levels – or certainly to those of us who are woefully ill-formed when it comes to bird life. Are there, for example, really birds called the Urban Council Skip Chick, the Ooshut Doorbang or the Gregorian Thwacksplatt? Sitting alongside the Turtle Dove and the Nightingale you could almost be convinced. Because the bird kingdom is absurd and their names and behavioural patterns, plumages and birdsong are perfect fodder for a caricaturist’s dream.

But the message remains: so many of these real birds are in critical condition and their survival depends upon the roll of a dice, the lowering of a cocked gun, the downing of a growling chainsaw. Or, in the case of, say, the Great Indian Bustard, simply keeping poachers, natural predators and grazing cows away from its rarest of grounded eggs. Conservation is often seen as sitting at the crossroads between science and politics, ecology and activism, and while pragmatism certainly plays a key part it is an awakening of the gamut of human emotions (sympathy, outrage, sentimentality) that will truly ensure the survival of many of these endangered birds, and indeed other threatened species of any variety. Humour is as powerful an emotion as anger, and here Steadman and Levy deploy it to devastating, educational and hilarious effect.