if a part of these heights

becomes water

the air breathes

in the north

(Nils-Aslak Valkeapää)

Yoik / Joik

Words: Jez riley French

I’ve long been interested in vocal music the lyrics of which I couldn’t understand – whether that be the early polyphony I sang as a choirboy in my youth, preferring to listen to how the voices resonated in the space than contemplate the religious imagery of the texts, the ebb and flow of Elizabeth Fraser’s voice as it combined all manner of linguistic hints and utterances, or my first experience of hearing Bulgarian folk song. I liked the sound of the words, their shapes and texture. Indeed, I believe my continued fascination with seemingly abstract sound can be traced through some of these early musical interests. I listen to a resonating surface, an empty building or sounds within an open landscape with the same enjoyment of how they bend and shift within their locales or during a period of time, not always knowing or wanting to know why.

During the 1990’s I owned a music distribution company that specialised in tradition based material, including importing releases from various countries around the world. This led to getting hold of cd’s on the Sami DAT label via a contact in Norway. At the time my knowledge of both the music and the complex political aspects of the Sami people was, like most, minimal but the impact of what I heard was instant. In particular I became interested in the yoik – a form of Sami vocal music, except that it not quite what it is. In fact it is quite hard to successfully describe and I confess that as I write this, I’m aware that there are aspects to it that I doubt anyone other than a Sami themselves could explain. Attempting to understand it one has to be careful not to think of it in along lazy paganism-by-numbers lines. It does indeed have roots in various myths and is strongly connected to the environment, but it is raw, visceral and intensely personal to each individual performer. It’s also a common over simplification to liken yoik to the wordless chants of other indigenous peoples, such as the inuit or native Americans. There is a similar unbreakable link with the land so that is hardly surprising, however for those interested in natural acoustics or the unrepeatable qualities of listening experiences, the fact that some Sami yoik can only exist in the environment, situation or time for which it is intended means that it has not been subjected to the same overly polished adjustments for the entertainment industry as some other traditions have. The use of natural surfaces, structures and conditions when performing yoik constantly affects the process, with minute changes signalling both the singer’s own reaction and the environment pulling the yoik away from them. For those of us who have a passion for open spaces a yoik is more akin to the call of an animal (for that is what we are) than to composed music in our understanding of that phrase. Some yoik does have words, sung poetry if you like, but the majority goes beyond the rules of conventional linguistic communication. The first time you hear yoik it can sound as if the same vocal phrase is being repeated over and over. However, just as listening for long durations to a single sound slowly reveals more and more, after a while one tunes in to the subtle changes of the human voice attempting to sculpt something fugacious in and of its location. As a field recordist it’s interesting to note that whilst lots of other sound based traditions such as folk song have gradually become almost entirely recorded in studio or concert hall settings, the Sami have retained an understanding of the yoik as one element in a wider soundscape. Indeed for the Sami certain yoiks simply do not exist elsewhere.

Although the work of the DAT label has helped document both traditional and contemporary Sami culture, those wanting to explore yoik still have only a small number of sources to aim for. Several key releases are long out of print in a physical format and much of the more recent material combines traditional yoik with various forms of contemporary music. Nothing wrong with that of course – that’s how traditions evolve and stay alive, with the younger performers breaking it apart and returning with new insights. For those keen to experience something of the yoik, as much as we can sitting in our living rooms, here are four albums that serve as a compelling introduction:

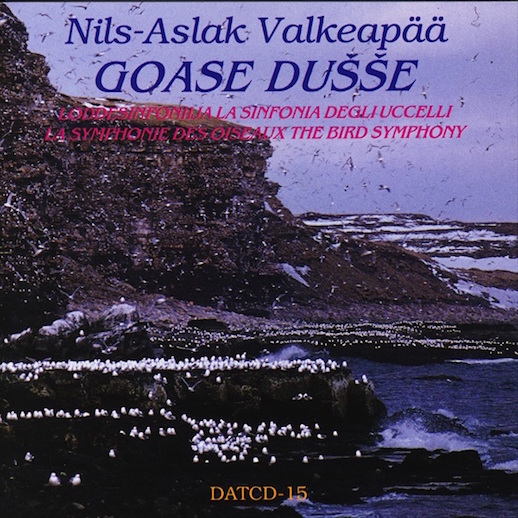

Goasse Dusse – Nils-Aslak Valkeapää (DAT) 1994

Goasse Dusse – Nils-Aslak Valkeapää (DAT) 1994

(The Bird Symphony/La Symphonie des Oiseaux. Prix Italia’s Radio Music Award for 1993. Valkeapää’s Bird Symphony received the jury’s Special Prize awarded by absolute majority for the imagination, poetry and technical excellence)

The work of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää serves as its own monument to this key ambassador of the Sami people. Across numerous albums, books and visual works Áillohaš, as he is known in the Sami language, created pieces that reflected a deep connection to traditional forms but also to new ways to dig out the very spark of them. Whilst he sometimes mixed yoik with musical elements, he kept such collaborations rooted in a direct conversation with the spirit of the yoik. The piece that I keep returning to most is ‘Goase Dusse’, an hour long sound picture combining field recordings of bird song, reindeer herds, storms and yoik. Currently the cd itself is out of print but copies can be found online, as can a digital download. The field recordings themselves are exceptional – that rare combination of clarity and a deep sense of connection to the location. Indeed that connection between human and place is at the core of Sami culture and when the yoik enters this particular piece, some 30 minutes in, one hears it as another species calling out into the environment, communicating with the material of place. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not ‘mystical’ in our western interpretation of that word. Just as we fool ourselves by listening to the sounds of a rainforest and thinking that they depict some idea of calm, so too it is possible to listen to yoik and convince oneself that there’s an affinity to something lost in our own societies, but we do so at the risk of missing something of the power of this living sound art.

Valkeapää, who sadly passed away in 2001 at the age of 58, was regarded as the father of modern yoik – routed in tradition but eager to enable new growth. He managed to enhance the profile of the Sami across the world, partly as a result of his commission for the winter olympics of 1994 and he yoiks he performed for the opening ceremony are available on the ‘Winter Games’ release (DAT), alongside pieces with the younger Johan Anders Baer and others.

the reindeer roamed the salmon climbed

grouse laughed the geese flew

the cloudberry ripened

(Nils Aslak Valkeapää)

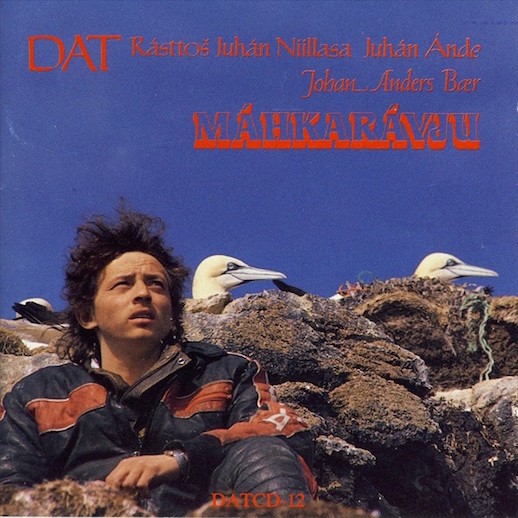

. Mahkaravju – Johan Anders Bær (DAT) 1992

. Mahkaravju – Johan Anders Bær (DAT) 1992

On Bær’s solo release ‘Mahkaravju’, now also out of print (again, available as a digital download however) he perches himself on the edge of the sea cliffs of the island of North Cape and performs traditional yoik, with the sound of the sea below and the gulls around him. Again, key to this album’s success is the way the environment has been captured. It hasn’t been air-brushed, glossed into a mere ‘nature’ album. The sonic experience of being precariously sat hundreds of feet above the sea with the cacophony of gulls competing with a single human voice pitching itself into the same air is both thrilling and unnerving.

Ruossa Eanan – Ulla Pirttijärvi (Warners) 1998

Ruossa Eanan – Ulla Pirttijärvi (Warners) 1998

Pirttijärvi was a founder member of Angelin Tytot, a group of young musicians who sought to bring yoik to a new audience. In her solo releases she has continued to mix Sami traditions with diverse instrumentation and touches of improvisation. ‘Ruossa Eanan’ (Russian Land) was her first solo album and brought some darker shading into her music. Unlike the other three releases mentioned this is a studio project and is therefore an example of how some Sami musicians have attempted to use yoik as a material for creative expression.

Unlike some vocal traditions yoik is not divided along gender lines and indeed Pirttijärvi comes from a long tradition of female performers who have both enriched traditional approaches and sought to expand on them. Of course one should also mention here Mari Boine, whose album ‘Gula Gula’ was licensed to Peter Gabriel’s RealWorld label in 1990 and did help raise awareness of the Sami people in the wider world.

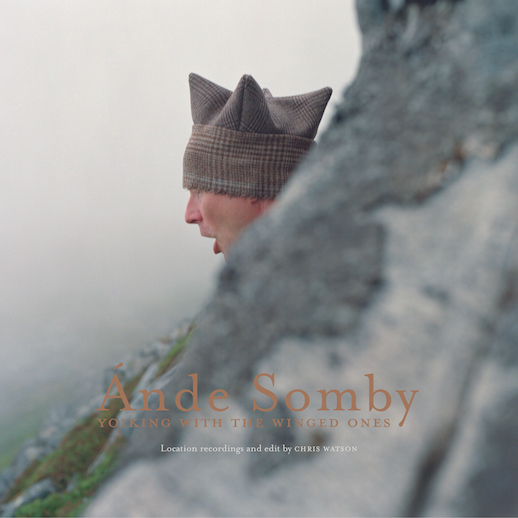

Yoiking with the winged ones – Ánde Somby (Ash International via Touch) 2016

Yoiking with the winged ones – Ánde Somby (Ash International via Touch) 2016

In recent years I haven’t kept up with all the releases of Sami music, and I confess I’m not that interested in some of the most recent fusion led work. However if one wants to experience something powerfully contemporary and at the same time routed firmly in the fabric of the Sami people, then Ánde Somby’s ‘Yoiking with the winged ones’ is worth hearing. Recorded in the field by Chris Watson, and also staged as a multi-channel installation, this is the sound of someone pushing themselves ever deeper into the moss and soil of their surroundings. Somby’s voice breaks, the yoik becomes fractured – exhaustion arrives and is submerged. Over the course of the 4 pieces we hear a voice stripped of its varnish, Somby’s particular approach of working up to and beyond the edges of his vocal abilities throwing itself out across the landscape. The recording captures, in Chris’s usual clarity, the landscape near to Kvalnes on the Lofotan peninsula, with Ánde’s voice echoing back and forth, rising above the bird song. One strand of my own work involves intuitive scores for musicians placed within the landscape as an equal element and a mark of the success of such pieces is when the hair on the back of the audiences necks rise up – that moment of intense listening, captivated by each second. A recording of such a piece that is capable of having the same effect by reproducing something of the location and the performer’s effect on it is, in my opinion, equally difficult to achieve. On ‘Yoiking with the winged ones’ Chris has done that. I have no doubt that it isn’t the same as standing there with the wind and Ánde’s voice coming at you from all angles, but it does capture more than mere documentation.

I spoke to Chris and emailed with Ánde to discuss the recording of the album, yoik and Sami culture:

CW: well, I knew nothing about yoiking really until I got an invitation from Ánde to go up to where he was living at the time, a place called Kvalnes in Arctic Norway, off the west coast and some way inside the Arctic circle. Ánde is also a law professor at Tromso University, so literally an advocate for the Sami people. Ánde had, I think, some kind of grant and was given the challenge of further promoting Sami Culture and decided a good way to do this would be to make a record of his yoik in the landscape so invited me up there in 2014. At the time Ánde was living with his then partner A K Dolven, the prolific Norwegian artist (1) near Kvalnes, this tiny fishing community, I’d say less than fifty houses, wedged between huge mountains and the Arctic ocean, amazing place, amazing culture I dropped into. So I stayed with them for a few days and Ánde explained that his idea with yoiking was to go into the landscape, vocalise and make these sounds, and that the echo that came back wasn’t an echo or reverberation as we know it, but was in fact the spirit voices of his ancestors answering him, because the Sami believe that we come from and go back into the landscape. The spirits of the ancestors live inside the landscape and they respond to the yoik by echoing these sounds. Ánde was concerned about several things including that the Norwegian government had granted mining rights to a British company to look for deep coal seams within Sami reindeer herding country, which really upset him. So, he created a yoik so he could speak to his ancestors and say ‘look, there are still people up here who respect Sami culture and we know what’s happening to the landscape and what might happen. There are people who think of and respect the old ways’, which I thought was a very powerful message. So I had great empathy with the whole thing.

Anna Katrine had found a lake which was about an hour’s walk up this very steep sided mountain, with no path, through heather, lichens and all sorts of Arctic flora. This astonishing lake was nestled in an elbow in the mountains, a few hundred metres across, very clear with Arctic char in it, rising and falling. Ánde would stand almost at one side, at a tangent across the lake and yoik and I would record his direct vocalisations from some distance; two or three hundred metres, but then I would get this incredible echo and reverberation coming back off the mountains which were all around us and it really filled the space. It amplified itself, almost like a standing wave. Ánde performed several yoik up there and it was quite an experience. For a start I had to walk up there, for about an hour up this very steep mountain, carrying all the gear. I kept stopping to get him to explain what he was doing, but also to get my breath back. I made a radio programme as well because I thought it was so fascinating. I used DPA’s (small personal mics) and just kept chatting to him and that’s the basis of a Radio 4 documentary about the trip. So, on the way I learnt a lot more about Sami culture, what he was doing and the reasons why. Ánde performed these pieces at the lake and then we came back down and went to another site where he performed his, quite well known now, wolf yoik.

The Sami believe you can migrate their spirit from humans into animals so Ánde did this amazing thing where he slowly evolves from Sami to wolf and back to Sami during this seventeen minute yoik. A bit like the bushmen in the Kalahari, there’s a kind of shamanic sense that they can pass their spirit into animals and become animals, think, feel and behave like them.

At the back of Anna Katrine’s house there’s a stretch of managed wilderness, not really a garden, which runs down to the shores of the ocean, where she has a boat and would go out each day, fishing for halibut and other fish for us to eat at night. But also there’s a lávut, a Sami reindeer herders’ tent, that we went in and again I learnt more about the culture as we sat around a traditional hearthstone, which was not only the centre of the heat but also of another aspect of Sami culture. Ánde told me about a goddess who sits in the fire with the hot coals on her lap, it was remarkable, and he performed some more yoik in there that I recorded, including a mosquito yoik. It was a massive cultural experience for me and I was fascinated by it.

JrF: Indeed. I know when I first started importing Sami recordings into the UK I knew very little about the cultural and political life of the Sami and there is a complex and interesting history. The relationship to the sound of their surroundings is of course of particular interest to us as we both spend a lot of time listening to environments. It’s one of the few vocal traditions on the European continent that has retained, fully, its connection to the environments it was created in and from.

CW: as far as I know, Ánde told me it’s the oldest vocal tradition in Europe. It’s interesting that you mention the political situation. Again I just didn’t know about that. Ánde is Sami – he’s a Norwegian citizen but he’s a Sami and that crosses all political boundaries. They don’t mean anything, particularly to a nomadic culture. This was all new to me, including how suppressed Sami culture has been by Norwegian society. It’s still illegal to yoik in Norwegian churches and Sami culture isn’t taught at schools, even in the far north.

JrF: Ánde, one of the things we’ve been discussing is how difficult it is to fully explain exactly what yoik is with the written word, especially in a language other than Sami. From your perspective could you tell us something about what the yoik means to the Sami people and to you personally?

AS: Yoik is basically a way to express oneself and mediate either a factual, poetical esoteric or magical message. The symbolic value of yoik is enormous. Yoik comes from time immemorial, and both the Roman empire, christianity and later different national states have had an ongoing war against yoik, but yoik is the definitive survivor. We used to say that you can burn my drum (when we reference when the shamanic drums were burned) but you can never ever burn the song that is inside me. Yoik is the stonehenge that is not made of stone.

JrF: Could you explain more about the origins of each of the yoik on the album?

AS: The wolf yoik is traditional. Me and the wolf have been on the road together ever since I started to perform some 40 years ago. The others are ‘máttuid cavgileamit’ – when our ancestors are giving us a little poke in the form of whispering us a yoik never yoiked before. ‘Gufihttar’ is a reminder and a praise to the underground people – fairies and elves (2) who gave us these strange wonderful songs in the first place. ‘Gádni’ is the ‘bridge’ or the energy between humans and the underground people. Neahkkameahttun is a praise and comfort to those who have lived physically and have stepped out.

JrF: Ánde is known for working with the edges of his vocal abilities and on this record, during the wolf yoik, you can hear that. As I’ve said elsewhere, and this goes back even to the earliest days of field recording, capturing any kind of performance recorded in the environment is tricky as it either serves as straight documentation or, on rare occasions, does convey something more experiential. Chris, I wondered how it felt to you, as a person – a listener rather than in your role as recordist, when he was pushing himself beyond his limits during the wolf yoik in particular?

CW: I think just experiencing these yoiks in the landscape was really quite moving for me. Several times I when I was recording them I took my headphones off and just listened because I could hardly believe it. First of all with the acoustic up on the lake and then with the wolf yoik. It was explained to me before we even started that this isn’t entertainment, it’s very purposeful. It was hard listening to it and I could see him as well though I was some distance away because I wanted to include, obviously, the landscape in the recordings as well. Although we went down into this soft sounding acoustic lower down the mountain, the microphone was perhaps 30 or 40 metres away from Ánde and I was a good 50 metres behind that, it was quite moving, physically, to see someone transformed. He did move from how I had known him an hour or so earlier to this half wolf like persona. All of the yoiks we could only do once – that was it. He did a short percussive whoop as a test for the echoes and for my benefit and then we were into it. The wolf yoik is seventeen minutes and once you start you’re in it for the duration. So it becomes quite a visceral experience. Physically and psychologically quite moving seeing someone put themselves through something like that.

JrF: Indeed. When I first started listening to yoik, and indeed when listening to any sound tradition from another culture than one’s own, inevitably there’s an element of hearing it as simply as music, and it’s only after delving deeper that you realise it often goes much deeper than that, that it’s not entertainment. Our own culture is largely based around the telling of stories, whether that be in song or spoken word, and music for dancing. Our distant sound traditions are mostly lost to us, as indeed they are in many countries. Hearing some yoik away from where or whom it was created for means one is only hearing one element of it.

Ánde, I know you have performed your wolf yoik in various locations and I wanted to ask you how you feel the yoik itself is influenced by the place in which it is performed?

AS: The wolf always plays along with the different spaces where we meet. It is so inspiring to hear from the audience that they get something powerful by listening to the wolf.

JrF: Chris, another aspect I wanted to discuss with you is that we are both used to listening very closely to environments for long durations so we’re quite good, I think, at picking up on really subtle changes – and I wondered if you could talk about any shifts you perceived in the general soundscape between Ánde’s vocalisations?

CW: I’m certain that he created changes within those locations and you can hear them. On the way up he was talking about how sometimes the birds respond, and they certainly did during the recording. There was a carrion crow and a cuckoo and almost a kind of call and response. Even the Arctic char rising in this unnamed mountain lake seemed to have some sort of rhythm attached to Ánde’s yoik. Part of creating this yoik is moving the acoustic of the landscape and when that happens then the things that live within it respond. It didn’t happen when we were there but he said that several times, earlier in the season, when he’s been up there and there’s been snow there has been snow fall, slippage in response to his yoiks, which is why I was convinced it was a special place and why he took the effort to get us all up that mountainside. He believes it’s a powerful place and when I heard him yoik in that environment and heard the response I could hear exactly what he meant. It’s strange because not only is it outside our culture it’s almost outside our understanding.

JrF: Yes, and I think one of the issues in terms of the wider perception of vocal based traditions is that some tend to almost group them all together as mystical chant rituals, but with a very thin and simple definition of such things. One thing that struck me about yoik is that it is raw and visceral. It certainly isn’t meditation music for mass markets!

An obvious question for you Ánde, but what do you hope listeners unfamiliar with yoik will get from hearing the album, given that because of the label it’s released on and Chris’s involvement does mean that it will reach some audiences totally unfamiliar with Sami sound culture?

AS: I think people in our time need to enjoy their traditions – to look back. They need to be in this moment – to be present in the presence. And they need to think forward – to be ready for the future. I hope people will both enjoy their past, their present and their future, and I think such invitations have to come in remote forms, from remote places and from remote times. I do it with both old and new yoiks and in orchestration with the wind, local crows, migrating birds and this fantastic sound faerie Chris Watson.

DAT, the Sami label and publishing house, is still active and in fact was cofounded by Ánde Somby. Let’s hope that at some point reissues of Valkeapää’s ‘Goasse Dusse’ and Bær’s ‘Mahkaravju’ are possible, helped by the interest of new audiences that Somby’s release via Touch can bring.

Jez riley French – January 2016

(1) A K Dolven’s work, for those readers not already familiar with it, explores the relationships between people and the perception of their environment – again, in a powerful and direct way. I recommend the book ‘Please Return’ (Art / Books) as an introduction to her work thus far.

(2) Readers should be aware creatures such as elves and faeries in Sami culture are quite different from other western ideas of them, which, until recently at least, have been somewhat sanitised through their depiction in children’s literature.

Jez riley French is an artist and field recordist based in East Yorkshire. He has created pieces for Tate Modern and Tate Britain along with galleries and arts organisations around the world. He also lectures and tutors on field recording, including alongside Chris Watson on workshops in the UK and Iceland. As well as numerous releases on the engraved glass label, early 2016 will see a new release via Touch records.