Small Town Talk : Bob Dylan, The Band, Van Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Henrix & Friends in Woodstock by Barney Hoskyns

Small Town Talk : Bob Dylan, The Band, Van Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Henrix & Friends in Woodstock by Barney Hoskyns

(Faber & Faber, 440 pages, hardback. Out now)

Review by Andy Childs

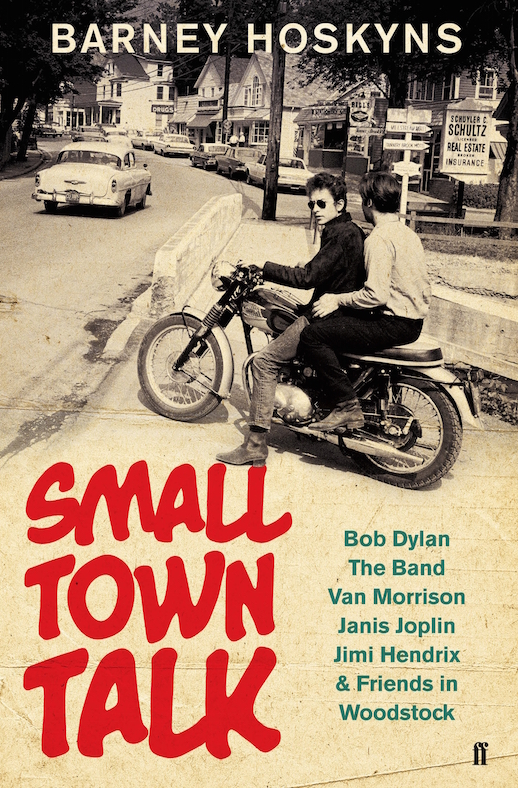

First of all the striking cover – a wonderful sepia photograph, probably taken in July 1964, of Bob Dylan and John Sebastian on a Triumph motorcycle, about to pull out onto a sleepy-looking street in Woodstock. The photo was taken by Douglas R Gilbert who, on his website, says that “In July of 1964, one year before his music changed from acoustic to electric, I photographed Bob Dylan for LOOK magazine. I spent time with him at his home in Woodstock, New York, in Greenwich Village, and at the Newport Folk Festival. The story was never published. After reviewing the proposed layout, the editors declared Dylan to be “too scruffy for a family magazine” and killed the story”. Luckily though, Gilbert’s photographs have survived, and this one is an instant enticement to pick up Barney Hoskyns’ engrossing, enlightening book and investigate. Dylan, looking scruffy indeed in jeans and scuffed boots and wearing shades, is half-looking at the camera as if to say “follow me, I’ll show you around town”. If we don’t have Dylan for a guide though (he was in fact notoriously reclusive when he lived in Woodstock) we have a more reliable and objective voice. Barney Hoskyns, the author of at least fifteen books on music, half a dozen of which are indispensable, is (I reckon) our most perceptive and qualified chronicler of American music in the late sixties and seventies. Having actually lived in Woodstock in the nineties and with a definitive biography of The Band, Across The Great Divide, already under his belt, he is probably best placed to unravel the tangled and turbulent cultural history of this most enigmatic and magnetic of places.

The Woodstock under scrutiny here is clearly not the momentous rock festival that took place in 1969 but the eminently more fascinating town, sixty miles away from the late Max Yasgur’s farm in Bethel, that has been a haven for artists of all kinds since the beginning of the 20th century. A less-than-wholesome anti-Semite named Ralph Whitehead and his friend Bolton Coit Brown chose Woodstock as the perfect site for the rural arts colony, Byrdcliffe, that they founded in 1903, and which, after Ralph’s death in 1929, his wife kept going for another twenty six years. “A refuge, a bolt-hole of wooded bliss where a man could breathe deeply and create in peace” as Hoskyns puts it. By 1914 a rival colony, the Maverick, was started by Hervey White, arguably Woodstock’s first hippie, and a year later the first major music event, the Maverick Festival, was held to raise funds for a well to supply water to the colony. The last Maverick Festival took place in 1931 by which time the Woodstock Artists Association had been founded and artists of all persuasions were taking up permanent and semi-permanent residence in this burgeoning bohemian paradise. Even film stars of the time such as Helen Hayes and Edward G Robinson were attracted to the place. But there was always, in Hoskyns’ words, an “uneasy alliance” between the left-leaning liberal minded influx of artists and the traditional, deeply conservative local populace and its local government. The established elders for the most part tolerated the newcomers more for the consequent upturn in economic prosperity than the social changes that ensued and that they continued to view with suspicion. This wariness still exists today as is very clearly evident in the final sentence of this book. But despite the local difficulties, over the succeeding decades Woodstock did indeed become established as a permanent artistic haven, largely unspoilt, unheralded on a national level, non-commercialised. A quiet refuge for musicians of all genres and artists of all disciplines. Being within striking distance of New York City, there was always a seasonal influx of folk musicians eager to escape the grind and confines of Greenwich Village. In the summer of 1959 the first Annual Catskill Mountain Folk Music Festival was held in Woodstock and the seeds of its reputation as a hotbed of American ‘roots music’ were planted.

This early history of Woodstock as a celebration of the benefits of a rural idyll on the artistic process is enthralling. While Hoskyns’ prose is succinct, lively and packed with information, I would have loved a more detailed account of the eccentric characters that fashioned this creative retreat, and perhaps a wider view of the artistic spectrum that existed there. But I’m being unfair here of course because that’s not what this book, in its explicit, lengthy title, purports to be about. Small Town Talk is mainly about what happened in Woodstock in the sixties onwards, after the arrival of one Albert Grossman and his wife Sally. It’s also, not coincidentally, about the events in a crucial stage in the career of Bob Dylan, the rise and fall of The Band, and tangential interludes in the lives of not only those luminous musicians mentioned in the title – Jimi Hendrix, Van Morrison and Janis Joplin – but Paul Butterfield, Todd Rundgren, Tim Hardin, Geoff & Maria Muldaur, Bobby Charles and Charles Mingus to name but a handful of the more noteworthy. The modern era of Woodstock and the accompanying mythology that was ratcheted up in the sixties and seventies began when Albert Grossman, a new and intimidating breed of artist manager, bought a house in nearby Bearsville in 1963. The following summer, eager to escape NYC after the break-up of his relationship with Suze Rotolo, Grossman’s top client Bob Dylan followed him there. Grossman, who had owned The Gate Of Horn club in Chicago, had moved to Greenwich Village, managed Peter, Paul & Mary and later The Band and Janis Joplin & Big Brother & The Holding Company, was reviled by many he did business with, but loved by the few people who managed to get close to him. A wealthy and powerful man, he set up his own fiefdom in Woodstock from which he controlled the careers of anyone deemed worthy of his attention, built his own recording studio and started his own record label in Bearsville, and, utilising the prestige that managing Bob Dylan gave him, played a major part in re-inventing Woodstock for a new generation. Grossman revolutionised the way musicians were managed, not least in the way he negotiated unprecedented recording and publishing royalties for his artists, trousering a substantial portion for himself. Nevertheless he was uncompromisingly passionate about his artists and their music, and of course, some of the music that was produced in Woodstock in its heyday continues to astound and influence artists today. The Band’s Music From Big Pink, perhaps Woodstock’s most celebrated artifact and an album that gracefully and effortlessly flew in the face of prevailing fashion, and The Basement Tapes, Bob Dylan & The Band’s gloriously shambolic and prescient foray into the “old, weird, America” are integral to Woodstock folklore – and are a significant reason why musicians of all species subsequently flocked there. George Harrison paid a visit, Fred Neil moved close by and a festival, The Sound-Out, was regularly held near his cabin in Saugerties at which The Soft Machine once played! John and Beverley Martyn recorded there, Van Morrison moved there, and Jimi Hendrix fell in love with the place.

Hoskyns chronicles this escalation in popularity in some detail, conjuring the impression of a magical, picturesque oasis where artists could interact and hone their creative instincts untroubled by the pressures and demands of big city life. He is also, soon enough though, equally meticulous in describing the ways in which a celebrity-orientated and “a very unsavoury hierarchy” developed, how a pernicious drug culture took hold and how Woodstock somewhat predictably lost its charm. Instrumental in instigating its fall from grace was also the fall-out from that festival. As Hoskyns puts it, “for many, Woodstock ruined Woodstock”. The town remained relatively quiet during the three days of ‘peace and music’ in August of 1969 but afterwards the hordes of curious “hippy drifters” descended in numbers and threatened to repeat what had happened in Haight-Ashbury a few years earlier. Dylan became disillusioned with life there (as well as with Albert Grossman who by all accounts embezzled him out of substantial publishing royalties) and gradually the eminent musicians and artists who had lived and worked in Woodstock in blissful seclusion began to leave. Tim Hardin left for London, Van Morrison decamped to Marin County, and eventually Dylan and then The Band moved to the west coast. Grossman stayed on however, nurturing his dream of establishing a Bearsville/Woodstock musical mecca, managing Janis Joplin, working with the precocious artist/producer Todd Rundgren, and growing his label and recording studio. Bobby Charles made a classic album there before his mistrust of Grossman’s business methods drove him back to Louisiana. But if the location, reputation and largely unspecified, mystical qualities of Woodstock continued to provide sanctuary for some, its drug and alcohol-fuelled underbelly was slowly draining the creative life out of it.

Hoskyns has been candid and sober in the past when documenting the havoc and destruction caused by a spiralling drug and alcohol culture, exacerbated by commercial pressures and interests, on music communities. His even-handed yet still startling account of the grossly self-indulgent L.A. singer-songwriter scene in the seventies, Hotel California, is perhaps the best example of his investigative and critical talents, and here he painfully, and with much sadness I would imagine, relates the eventual downfall of The Band. Their problems were rooted in a turbulent mix of animosity towards guitarist Robbie Robertson (who has claimed sole songwriting credits and therefore substantial royalties on songs that were deemed by the rest of the band, particularly Levon Helm, as group efforts), dissatisfaction at the way they were being managed by Grossman (no surprise there), pressure to emulate their first two near-perfect albums, chronic alcoholism and debilitating drug abuse. Miraculously they went on to release another five albums in the seventies but their demise was inevitable and with it the fading of the light in the heart and soul of Woodstock. After Albert Grossman died on a flight to London in January 1986, Woodstock was never really the same. In 1994 there was another Woodstock Festival, this time nearer the town, but it did nothing to revive the town’s fortune, and now Woodstock “has all but ossified into a musicians’ retirement home”. There is still a music scene of sorts there and up until 2012 when he died, The Band’s Levon Helm, who’d moved back to his spiritual home, hosted The Ramble in the Barn, a series of concerts that featured guests such as Allen Toussaint, Jackson Browne, Kris Kristofferson and Elvis Costello. And while the dream of Woodstock-as-artistic Shangri-La has faded away, it survives. Its location is still spectacular and the idea of the rural idyll is once again becoming an attractive lifestyle choice, but it’s hard to imagine it ever regaining the heightened status and cultural significance that is so entertainingly celebrated in this book. Included are a very useful map of the town (with all the relevant landmarks noted) and a playlist of “twenty-five timeless tracks” – to make the point that more often than not, the music justified all the hype. Small Town Talk is an important addition to a fuller understanding of how American music was shaped in the late sixties/early seventies, and is an impeccable guide to much of what was truly great about it.

Small Town Talk is accompanied by a Spotify playlist compiled by the author.

The book will be launched at Rough Trade East on 3 March, with discussion and live performance from Barney Hoskyns, Graham Parker and Sid Griffin. More info here.