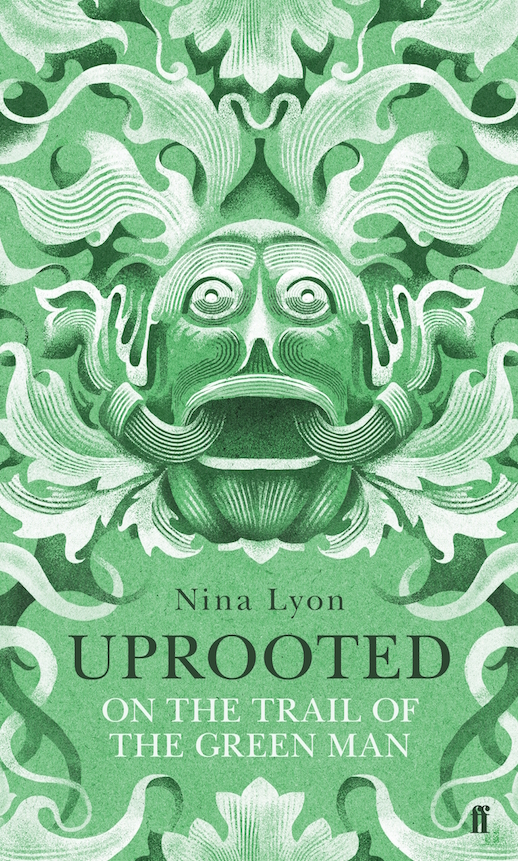

From Uprooted: On the Trail of the Green Man, our Book of the Month for March. Out now and available in the Caught by the River shop for the special price of £12.50.

From Uprooted: On the Trail of the Green Man, our Book of the Month for March. Out now and available in the Caught by the River shop for the special price of £12.50.

Words: Nina Lyon

What seems to be the white noise of the wind is, on closer listen, both polyrhythmic and multi-tonal. There is a single background hum and, weaving around it, the rise and fall of other winds: sidewinds and crosswinds and eddies. The house is on a hill, or, to be more precise, on the head of a ridge running off a hill into the Wye Valley. You can therefore, on a clear day, see down the valley in both directions, and across the valley to the Hergest Ridge and, behind it, the Radnor Hills, which are sometimes dusted with snow. Behind the house’s promontory is Little Mountain, which is not really a mountain, but a big hill.

You can see everywhere, and the wind can get everywhere. Perhaps because it comes from everywhere at once, channelled down the broad valley but refracted through many other places, it creates a cacophony, always altering, never resting. While the patter of windless rain is calming in its soft consistency, there is something rousing about the wind, which is not relaxing. It is like a restless chant.

It was after another white night of wind that I drove, sleep-deprived and in a condition not suited to adverse road conditions, along the length of the Golden Valley as it follows the path of the Dore down from the hills that loom above the Wye. The road was, in its better parts, a conduit for water flowing from one field to the next and, when it sloped, a waterfall. This was a good thing, for the movement of the water meant that it did not pool deeper. Red mud coursed along past abandoned cars left in last night’s floods, which had, for the moment, subsided. The static bodies of water were the scary bits, because you did not know where they would end. There were fewer of these, but the road had been carved away at its edges, which fell aside like glacial moraine, and the road, like the washed-out cars, looked fragile. An unremarkable journey alters when its success cannot be taken for granted. The water was winning.

We live in an age controlled by humans and human technology. One current assumption, the pessimist’s, is that human technology is so efficient and invulnerable that it will, eventually, kill off the planet. The optimists take a different line, which is that human ingenuity will evolve to solve all problems regarding human survival. Both rest on the assumptions that human ingenuity is unique, for good or for bad, and that human technology is more robust and powerful than nature. It took a month of angry storms to make me consider this more critically than before.

There was something about the surfeit and force of elements that made me want to go back to Kilpeck, which is where I was headed. I felt as though the aggressions of the weather might make more sense there, or perhaps that Kilpeck would make more sense in the light of the storms.

Kilpeck is a village in Herefordshire, about twenty miles away from my home near Hay-on-Wye. The village itself might have come straight out of The Archers, a westerly Albion of rolling hills and well-kept pretty cottages and a smart-looking pub with good food. At its edge are two noteworthy things: a motte-and-bailey castle and a church, which is not really, to my mind, a church in any conventionally understood Christian sense at all.

In the eleventh century, the parishioners of Kilpeck would have been trying to understand their landscape and the weather that altered it as an expression of a greater will. As human endeavour moulded the land, with clearings and mounds and buildings, so it was moulded by the land, existing in conflict, and in symbiosis, with nature.

Our rational belief in a mechanistic world of things enables us to find effective ways of operating in it, and our ways of operating in it further build that belief. We seem to be very adept at shaping the world to our will, and think little of the idea that the will and the ways of humankind might fall prey to any entity other than our own self-destruction.

But this sustained attack from untamed nature together with a big cultural wave of environmental doom-tales had made me question our narrative of human progress, our sense that comfort can be gained from our capacity to build and improve our world. It all seemed a bit anthropocentric. People looked small on stormy days. Once upon a time, the storms would have been attributed to a pagan deity of some kind, or an angry Old Testament God.

I was not in a mood for finding God or redemption, or, for that matter, its pagan equivalent. I was interested more in how to simply understand a relationship with nature and the land in which both were considered to be alive, and not just alive but conscious. I wanted to get into what I had come to think of as the Kilpeck headspace.

There is a sense of godliness revealed in nature that characterises the architectural decoration and, I would venture, would once have characterised the creed of the Kilpeck church. I was starting to wonder if taking a worldview which encompassed the idea of a will that is everywhere, whether of God or object or ether, might actually be a more practical way of understanding the things that modern-day scientism sometimes doesn’t.

The rain had stopped and the wet road, lit up in the first sunshine for weeks, glared its path to the village. The church stood, calm and flesh-pink in the new light, as though the storms had never happened. Behind it, through a yew-lined uphill avenue, the ditch around the castle motte had flooded into a moat, cutting it off apart from a foot of raised track. Rather than concealing the structure of the space, the water clarified its depths and heights and the even circle of the motte. Now that the rain had stopped and the sky was blue, its bright reflection shone in the flash moat.

Behind the castle tump, above the spiky tips of a pine forest, loomed the massif of the Black Mountains. Today the mountains were not black, but white with snow. As I drove back down the Golden Valley later, the snowline looked as though it were painted on in one vast stripe along the Cat’s Back. Birds sang from above the village. Beneath us, I thought I could hear a distant hum, or roar, and braced myself for revelation, but it was the A465.