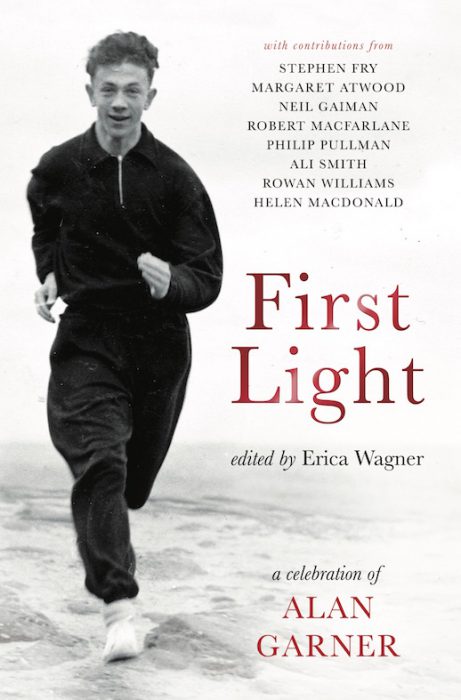

First Light: A Celebration Of Alan Garner

Edited by Erica Wagner

Unbound, 316 pages, out now. Buy a copy here.

Review by Ben Myers

Alan Garner occupies a unique space in the modern literary world – and as a “a shallow recess, especially one carved or set in a wall” niche is perhaps the correct word. He is either Britain’s best living writer or someone that large swathes of book lovers simply haven’t heard of, much less read. Press coverage is sporadic and scant in relation to the magnitude and durability of his novels, the visibility of his books unpredictable and public appearances are minimal.

His career – and that is definitely not a word that should be used to describe the work of someone who is reaching beyond the limitations of physical form and place to leave work to ring down the ages – is certainly a series of contradiction. He is the children’s writer who only ever wrote, simply, for people. The fantasy author for readers who do not always read fantasy. The iconic figurehead for a certain strand of literature that explores landscape, history, time and all things chthonic, who remains barely publicly recognisable, instead preferring to publish works as and when he sees fit, ensconced in his medieval house, Toad Hall, deep in the Cheshire landscape in which much of his work is set.

On this subject I have a confession: I recently met Garner at an awards ceremony and though we exchanged brief small-talk I was largely too in awe to say much, not least because he is on record as saying “I avoid writers – I don’t like them.” Only when he and his wife Griselda were leaving the building did I decide to pursue him to get a copy of his recent novel Boneland signed. It’s something I never do – Chuck D was the last person whose autograph I got, and that was in a different millennium. Nevertheless I ran through two rooms and down a hotel corridor before cornering him at the lifts. Slightly out of breath, I held out the book and pen. He smiled and shrugged, a little embarrassed. “I’d love to sign it,” he said. “But I’m afraid I’m not Alan Garner.”

And he wasn’t. This man was a local councillor or a dentist or a civil engineer. But he definitely hasn’t Alan Garner. Alan Garner had left the building. And though I had met the real Garner just minutes earlier I still did not recognise him now, the myth of his work somehow far overshadowing his actual physical presence there in a room in Manchester. The idea of him and the themes of his stories had made a greater impact than our awkward exchange after which I had no memory of his face or what had been said. It was as if I had been set adrift in time, disorientated, yet exhilarated.

Through my embarrassment I consoled myself with the possibility that this story, were he ever to hear it, might have tickled this man who continually shuns the tawdry carousel of what Quentin Crisp called the “smiling and nodding racket”. Garner’s stories go beyond literature. They are as old as the hills.

Rather than viewing him in terms of the fickle contemporary book world, he is perhaps best understood as a modern myth-maker whose work is part of a lineage that takes in the anonymous poets who crafted Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and on through the best efforts of Geoffrey Chaucer, JRR Tolkien and JK Rowling and, indeed, many of the authors included in this anthology, such as Neil Gaiman, Margaret Atwood, Philip Pullman, Helen Dunmore, Ali Smith and Paul Kingsnorth, who all contribute to a mosaic of appreciation, response and reflection.

If Garner is known for anything it most likely for 1967 novel The Owl Service, filmed for TV two years later, and now regarded as something of a touchstone work for the current interest in all things that fall under the broad catch-all term of ‘folklore’. Similarly, his era-straddling 1973 novel Red Shift was adapted for as a Play For Today – once seen never forgotten.

It is his non-young adult work that truly resonates: his 1997 collection The Voice That Thunders is perhaps the best collection of essays and lectures on writing, sense of place and identity I’ve ever read – his essay ‘Fierce Fires & Shramming Cold’ on the subject overcoming the “endogenous depression” (triggered while listening Benjamin Britten on April 16th, 1980) that lead to him being near-catatonic in the foetal position for two years should be prescribed on the NHS. His novel Strandloper meanwhile is a linguistic pyrotechnics display that spans, countries, continents and ages, a true modern classic that is rarely to be found on lists that collate such titles.

Nevertheless writer and editor Erica Wagner has done an excellent job in drawing together the many tangents of thought that spring from Garner’s work. Other contributing writers include Helen Macdonald , John Burnside, Rowan Williams, Frank Cottrell Boyce and Olivia Laing, each clearly indebted to the influence of Garner for a plethora of varying reasons, chief among them the importance of story-telling in our culture. In all cultures.

Phillip Pullman is not the only writer to note that Alan Garner comes from a long line of craftsman and stonemasons, and it is these – rather than writers – that he bears the closest resemblance too, and that for him “words have weight and shape and music and taste”. Stone runs through his writing as is does the northern soil: deep and true. It’s there in The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, The Stone Book Quartet, Thursbitch and beyond.

Each of Garner’s novels feel as if they have chipped down from great hunking, hewn slabs to perfectly formed objects, whose weathering is only improved by the passing of time. Writing about First Light it is hard not to fall in line with the appreciative tone of the many essays within. But Garner is a rare writer, a man out of time, a sage, prophet, chronicler of an ever-changing England and a singular voice. This homage does him justice.