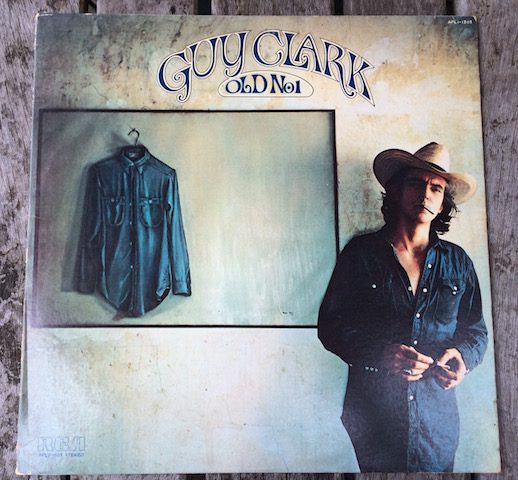

As storytelling songwriters go they don’t come much better than Guy Clark, the Texan master of the artform who died this week aged 74. Fellow fanboy Jerry David DeCicca pays tribute:

I was a 19 year old that felt like an 85 year old. Belly full of ulcers, lots of bad habits, multiple prescriptions. Then mononucleosis got the best of me, and I dropped out of school. I was shipped back to southern Ohio and onto my parents’ couch while the life I couldn’t handle moved forward. I spent that spring bedded down in the basement, watching TV, listening to the radio, and playing guitar. The second day I was home, Kurt Cobain took his own life. I’d flip between MTV and VHS tapes, falling in and out of sleep for the next month.

Listening to WNKU, a local public radio station based out of Northern Kentucky University, I learned that Guy Clark was performing there in early May. I had never heard of him or his songs, but the ads called him a “Texas songwriting legend.” That was enough for me to leave the house for the first time since coming home. I borrowed my parents’ Grand Am, paid the $12 to get in the door, and sat down in the auditorium by myself. I must have been the youngest person there by at least a decade.

Clark’s songs seemed to take life on the chin, something I was too young and dramatic to know anything about. They recognized hardship, but felt joyful. His characters were rivers and step-grandpas, little kids, lovers and town drunks, bowls of chili and tomatoes, places I had heard about, but never been. I loved the way he sang the word “son-uva-bitch” in “L.A. Freeway,” and I remember hearing “Dublin Blues” — even though he didn’t release it for another year — and thought how it was great that he mentioned a Doc Watson song in the same breath as work by Michelangelo and da Vinci . I didn’t understand “Randall Knife” on first pass — and I don’t think anyone does — but I knew I wanted to hear it again. Landscapes and geography felt essential to the characters. Personal and public histories were blurred. The songs felt exotic and from a world that no longer existed. At that time, I hadn’t been west of Chicago.

Everyone talks about the poetry in his songs, but what I liked about him first was his voice, his guitar playing, and the way he looked. Dressed like a bookish rancher, he sounded thirsty, like his throat was dry from the ride in. He was masculine, but never macho. He played licks on his acoustic, not just chords, pulling on the strings with his thumb and fingers. Each song felt distinct and fully-formed with just his guitar and voice. I remember watching his large hands play an A chord as his pinky finger reached to play the high E string on the fifth fret, and how that small detail helped him create stronger melodies. It was the first time I’d seen someone do that. His son, Travis, was playing bass, and I thought how incredible it must be to have Guy Clark as your dad, taking you on the road and playing music together. It didn’t occur to me what that must have been like growing up.

I’d go to see Guy Clark every time he came around after that. Once at a Jimmie Rodgers tribute in Cleveland, another time at an old fire station in Columbus, and a handful of other times scattered in small halls around the Midwest. And each time I saw him, I’d notice how stoic and playful his songs were in their rhymes and rhythms. It’s a rare combination.

The last time I saw him play was at folk festival in Nelsonville, Ohio. We were both backstage poking around the food. I thought this was my chance to finally talk to him, but before I could say anything, he looked at me and said, “Someone told me there was supposed to be some BBQ back here. This isn’t goddamn BBQ! This is Sloppy Joes!” as he held a sandwich that wouldn’t have been able to cross the state line into Texas. The poet had finally spoken to me, and I mumbled something back about the veggie tray before he stomped away. We met again backstage an hour or so later as he was about to go on. He handed me his guitar and said, “Can you play this?” He wanted it out of his hands so he could roll a smoke. I picked the guitar a bit, and he complimented me, said I played “real clean” and he liked that and to keep playing. I tried to make conversation about Heartworn Highways, our mutual pal, Larry Jon Wilson (who Clark kept a tape of at his workbench), and the gigs I’d seen him play, but he wasn’t very interested in talking. He said, “You keep warming up that guitar for me so I can smoke this.”

So I stood in front of Guy Clark, just the two of us, and played his guitar for about 10 minutes while he smoked before going on stage. We exchanged only a handful of words. He didn’t want to chit-chat.

I live in the Hill Country area of Texas now, which is where a lot of his best songs take place. I hear “Rita Ballou” in my head every time I go to the honky tonks. And when I’m down by the Gulf, around Corpus Christi where Clark grew up, I think of “The Ballad of Laverne and Captain Flint.” If you ever get the chance to come down this way and drive around off the interstates, listening to Old No. 1, make sure you take it. There are still dance halls, chili cook offs, crawfish boils, and drunks in parking lots. Guy Clark may no longer be with us, but his songs and the lives they captured are still breathing all around us.

Guy Clark, November 6, 1941 – May 17, 2016