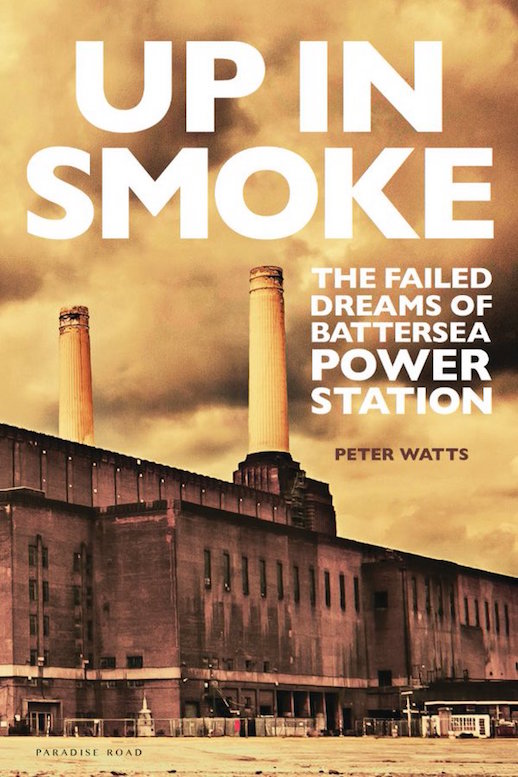

Up In Smoke: The Failed Dreams of Battersea Power Station by Peter Watts

Up In Smoke: The Failed Dreams of Battersea Power Station by Peter Watts

(Paradise Road Press, 272 pages, hardback. Out now.)

Review by Alister Wedderburn

Growing up in London’s south-western suburbs, Battersea Power Station marked the threshold of the big city. On the train into Waterloo it would appear to the left as the track bent round towards Vauxhall, standing guard over its patch of wasteland. It was mysterious, but also custodial, and it existed in what seemed then like an eternal state of proud desolation.

In 2013, Will Self described the power station as an ‘Ozymandian monument to Butskellism’: a relic from a long-lost past of cradle-to-grave welfare and nationalised industry. It undoubtedly is that: Battersea rests on the riverbank like a mudskipper, the obdurate vestige of an earlier evolutionary age. But it’s something else, too. Since its closure in 1983, an unfathomable amount of time, effort and money has been spent trying to give Battersea a living, breathing future. For a generation now, the station has functioned as a screen onto which the ambition and the imagination, the whimsy and the vanity of a series of rich men has been projected in trying to achieve this aim.

In Up in Smoke, his well-researched and effortlessly entertaining new history of the power station, Peter Watts tells the whole, long story of the site, from its industrial past to its future as a gated millionaires’ reserve. Yet it’s the bit in between – the years of dereliction, in which four owners saw their best-laid plans frustrated by the sheer scale of the project they’d taken on – that might well speak loudest to those who, like me, never saw the chimneys smoking. Battersea’s recent history is one in which far-reaching and ever-changing relationships between power, capital and urban space can be traced: this is the story not only of a building, but of a city.

*

What the world knows as Battersea Power Station is actually two near-symmetrical stations sat back-to-back. They weren’t even constructed together: the first, built between 1929 and 1935, stood alone for twenty years before being joined by its twin. With the pre-war completion of the National Grid and the post-war development of nuclear power, however, urban coal-fired power stations were never likely to enjoy a long lifespan. Battersea’s A and B stations were decommissioned in 1975 and 1983 respectively, and the Central Electricity Generating Board immediately set about selling the site into private ownership.

The problems associated with developing the Battersea site are huge. The building is listed, meaning demolition or significant alteration is near-impossible. It’s vast: large enough to accelerate a car from nought-to-sixty within its walls. It has no windows, limiting its possible conversion options. In 1983, there was a further complication: London’s population was falling and its housing market stagnant. The CEGB nevertheless managed to sell the station to David Roche, who had formed a consortium intending to build a funfair themed – implausibly – around British industrial history.

Roche was swiftly bought out by a member of his own team – John Broome, the founder of Alton Towers – who immediately set about making a series of outlandish, Lyle Lanley-esque guarantees and theatrical public displays; smoke-and-mirror promises seemingly backed up with very little concrete progress. In 1988, Margaret Thatcher was persuaded to don a hard hat and fire a laser gun across the site in order to commemorate the naming of Broome’s project (‘The Battersea’) and the announcement of its opening date – a date which duly came and went without much activity in the interim. Hamstrung by all sorts of financial and practical difficulties, Broome sold up in 1993.

Broome’s sale marked the first time Battersea ceased to be a British asset: the new owners were Parkview, a Taiwanese investment firm. Watts’ chapter on Parkview’s thirteen years in charge moves startlingly quickly, an indication of the speed at which the firm’s intentions for the site changed. The Taiwanese fluttered between a bewildering panoply of ideas: two different ideas for theme parks (again); a hotel, exhibition and leisure complex; a casino; a gallery space; a race-track; a permanent base for Cirque du Soleil. Few progressed much further than architectural drawings. In 2006, however, when the Irish-owned Treasury Holdings took over, London’s social, political and economic milieu had changed beyond recognition. For the first time, a residential-led development was mooted, and whilst the 2008 financial crisis killed off Treasury Holdings’ involvement, SP Setia, the Malaysian conglomerate who purchased the site in 2012, picked up the slack.

It is SP Setia who are in charge of everything happening at Battersea today. The irony is that after three decades attempting to transform the station into a viable private venture, it has been state money that has finally unlocked Battersea’s potential as a profit-making investment: SP Setia is backed by Malaysia’s largest state pension fund. There is a tendency to see Battersea as emblematic of a wider societal shift from state collectivism to individualistic profiteering – Butskellism to Lanleyism, perhaps – but the Malaysians’ apparent success hints at something slightly different. Battersea, it seems, is not so much a symptom of the private sector’s triumph over the public, but rather of the way in which the two are now closely woven into one another, a Venn diagram featuring two overlapping circles indistinguishable but for narrow crescents of independence at either edge.

*

These days, I don’t often take the train when I go back to see my parents. I usually cycle, along a route which takes me down the Chelsea Embankment, just a river-width away from the station. It’s the only viewpoint left from which Battersea isn’t completely lost in a thicket of half-built luxury flats. After more than thirty years of staunch intransigence, it seems the power station has finally been conquered. And how. In 1984, David Roche was able to buy the entire site for £1.5m. Today, that sum would just about cover a 48m² studio flat in the Eastern Switch House, bought off-plan. Ultimately, Battersea’s story describes the classic post-industrial, neo-liberal journey of urban development: the journey from powerhouse to power house.

Further reading – The Great Wen: A London Blog

Alister Wedderburn on Caught by the River