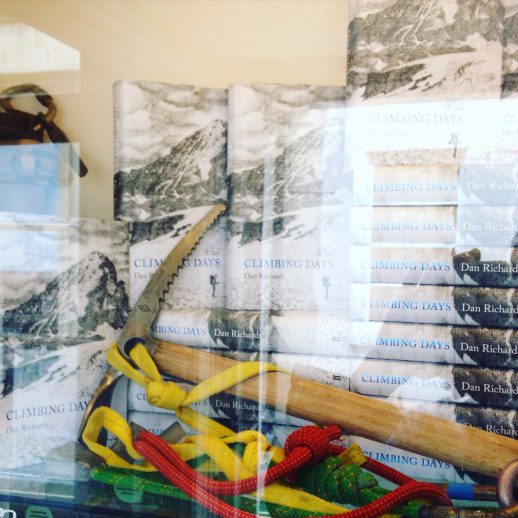

Window of Mr B’s Emporium, Bath, featuring Dan’s climbing kit

Window of Mr B’s Emporium, Bath, featuring Dan’s climbing kit

Climbing Days by Dan Richards is the Caught by the River Book of the Month for June (Faber & Faber, hardback, 385 pages. Available here, priced at £14.99.)

Review by Andy Childs

In Joe Gould’s Teeth, Jill Lepore’s provocative re-evaluation of the Joe Gould story (he of the famous Joseph Mitchell New Yorker profile), she asks the question: “What is biography?” and muses on “the error of believing that you can ever really know another person”. And she quotes Gould as believing that “the fallacy of dividing people into sane and insane lies in the assumption that we really do touch other lives”. A tough question. Can biographies ever enable us to touch the lives of others? Really understand what made them behave the way they did, do the things they’ve done, say the things they’ve said? How they thought and felt? It’s one of the most common criticisms to be found in reviews of biographies – that we can know everything about family history, know every place visited, hear from every friend with an opinion or an anecdote, know every move inside out, but still not connect with the essence of who the subject really is/was. Is it even possible or desirable to know someone that thoroughly? Such is the biographer’s burden, which prompts another question : is the standard form of biography at best inherently flawed and at worst completely redundant? Safe answer – probably not, but interestingly a particular strain of intrepid and unconventional biographical writing has spawned some extremely bold and memorable books recently. Threads: The Delicate Life of John Craske by Julia Blackburn is an outstanding example, as is this book – Dan Richards’ homage to his late great-great Aunt Dorothea Richards and her life-long obsession with mountaineering. As so much recent travel literature and nature writing has encompassed other genres, so some of the more ambitious biographical projects are as much travelogues, memoirs, and history lessons with the occasional philosophical digression. Such licence to extemporize of course can, and probably already has, enabled lesser scribes to trivialise and homogenize a potentially exhilarating concoction of scholarship, adventure, humour and metaphysics, but in the right hands and with the right subject the results can, as Dan Richards proves here, be revelatory and profound.

Climbing Days is, a little confusingly, also the title of the book that Dorothea Richards wrote in 1935 about her time mountaineering in Wales, the Lakes, the Alps and North America up to 1928 with her husband the literary critic, scholar, and fellow mountaineer Ivor Armstrong Richards, and it is Dan Richards’ trusty guide in his pursuit to re-trace her steps and to try and connect with her remarkable life and spirit.

Dorothy Pilley was born in 1894 and from an early age showed signs that she would become an immensely strong-willed woman – unorthodox, unpredictable in social situations, determined to have her own way, but with liberal sympathies and an untameable thirst for adventure; “an inclination to be a great lady with an equal and opposite desire to be off with the raggle-taggle gypsies”. After a patchy formal education she did ‘war work’ in the 1914-18 conflict and later worked as a reporter for the Daily Express and as a freelancer. But by that time her passion for mountains and mountaineering, originating with a hike up Mount Snowden on a family holiday, had taken hold of, and was directing, the rest of her life. Having met Ivor in 1917 they climbed together in Wales, the Lakes and the Alps. In 1921 she was instrumental in founding the Pinnacle Club – a women-only climbing organisation, became secretary for the British Women’s Patriotic League, and in 1926 Dorothy Pilley became Dorothea Richards when she and Ivor were wed in Honolulu. With her husband’s various appointments abroad they proceeded to climb prodigiously in China, Japan, Korea and Canada. Anywhere they could. By the late 50s they were living in the U.S. and it was there that Dorothea was involved in a car crash that left her with a damaged hip. Impaired but hardly impeded she continued to climb and her last serious ascent was in 1968. Six years later they moved back to the UK, to Cambridge where she lived the rest of her days. These basic facts, intriguing as they are, barely hint at the richness and dynamism of her life and part of Dan Richards’ success with this book is to embellish them with what must have been a substantial amount of scholarly research, the reliable testimony of those who knew her, and a good deal of leg-work (literally). He also quotes liberally from her Climbing Days and as a result she comes vividly to life on these pages and propels Dan’s book along at a steady pace.

By his own admission Richards had no clear idea of what kind of book he was writing when he started. He didn’t want to write a straightforward biography or a book just about mountaineering so he took his cue from Ivor of whom the critic Frank Kermode once said : “he liked best to start a book and then, writing with great speed, find out what the book wanted to be”. This book obviously wasn’t written at great speed as Richards engrossed himself in mountain literature and decided set about re-tracing the steps that Dorothea took in her Climbing Days as his “bridge into their lives”. First stop was Rye in Sussex where he meets Dr.Richard Luckett, a friend of Dorothea and Ivor late in their lives and at this early stage in the book it becomes clear just how important a figure Ivor was to the trajectory of Dorothea’s life and to the shape that this book takes, even though he remains an elusive if fascinating and complex character. He was a distinguished academic (which Dorothea wasn’t), he was much more well-known generally than Dorothea, he hated the past “for its suffering and cruelty” and always looked ahead. There exists a vast, impenetrable biography of him by one Jean-Paul Russo which Richards has successfully dissuaded me from reading, and Dr.Luckett himself wrote the introduction to Selected Letters Of I.A.Richards, valuable source material on someone who “famously disliked autobiographical writing”. Dr.Luckett, a very genial-sounding fellow, talks fondly and revealingly of them both.

Next it’s to Cambridge where Ivor first attended Magdalene College as an eighteen year old to study philosophy and then returned there as a don with Dorothea, who apparently wasn’t exactly comfortable playing the role of a don’s wife, where he was an eminent individual and she was a nobody. It seems that it was also at Cambridge that he developed his aptitude and enthusiasm for climbing, regularly scaling the readily available steeples and towers, a practice known as “buildering”. From there Richards travels to Conwy in Wales to find out more about the still extant all-women Pinnacle Club. Following the trail that Dorothea took in 1933 he climbs with three of its members, not altogether pleasurably or successfully it must be said. It’s an endearing feature of this book throughout that Richards is amusingly self-deprecating about his own attempts at climbing, an unduly modest stance to take I would suggest, particularly when you consider the foul weather that continually seemed to plague him and the unforgiving nature and calibre of his chosen companions. I also found the light touch in the present-day travel narrative that binds together the many strands in this book a welcome counterpoint to the relentless list of Dorothea and Ivor’s celebrated climbing achievements, allowing Richards to follow cheerfully and respectfully in their wake.

His adventures in research and ignominy take Richards next to the Cairngorms, one region that Dorothea doesn’t actually appear to have climbed in, and he’s there primarily to prepare for more rigorous and demanding mountaineering. Unbelievably arduous and dangerous as it sounds, Richards emerges intact and then it’s off to Barcelona to meet with Dorothea’s nephew Anthony Pilley. Having developed a great friendship with Dorothea, he provides Richards with useful background on her early years, talks about her diaries, and has a recording of her made when she was 91 during which she talks about her climbing life. Imbued with some of the same qualities as Dorothea – stubborn, impulsive, non-conformist – Anthony is as close to her as we could possibly get now and he is a surprising and interesting character in his own right. Music rather than mountains seems to have played a major role in his life – there’s a lovely photo in the book of him fronting his band The Fantoms in 1964 and he ran a recording studio in Edinburgh where Aztec Camera made their early demos. Such unexpected asides serve to reel in the years and strive to make a connection for us. I should add that, enjoyably for this reader, there are several musical references throughout the book, the most amusing of which concerns the incident in which Richards’ father and his brothers played ‘Baba O’Reilly’ by The Who really loudly for Dorothea and Ivor in order to try and elicit “some sort of emotional response”. The mind well and truly boggles.

After a touching scene in which Richards is presented by Anthony with one of Dorothea’s fountain pens, he’s off to undertake what will become the lengthiest and most gripping part of his book – his attempts to scale The Dent Blanche, “one of the great summits of the Swiss Pennine Alps”. Dorothea and Ivor first climbed its north-north-west ridge in 1928 and in 1981 Richards’ father Tim repeated the feat in an attempt to engage with Dorothea where he had previously failed conversationally. Alas, even though she lived for another five years she was never to learn of Tim’s achievement. This time though it’s a father and son expedition as Dan and Tim, enduring the usual rough weather and a catalogue of mishaps (some self-inflicted but all borne with admirable stoicism) fail heroically in their attempt on The Dent Blanche (you can read an extract elsewhere on this site). There is much about the art of mountaineering in this section of the book which, if nothing else, proves conclusively that Richards knows what he’s talking about – even if he implies on more than one occasion that he doesn’t utilise his knowledge as effectively as he might.

Undeterred, and after a climbing sojourn in the Lake District which sounds like another exhausting ordeal, he’s back in Switzerland for another attempt at The Dent Blanche, this time with an experienced, professional guide named Jean-Noël Bovier. Again, it doesn’t sound like much of a recreational experience. Jean-Noël, a hard task-master and agreeable enough at first, at some point, in Richards’ words, “took umbrage at my ineptitude in crampons”. Although they reached the summit it appears to have been a gruelling, perilous and bad-tempered experience. To think that Dorothea and Ivor scaled the same heights nearly ninety years before them on relatively unmapped terrain and with no doubt less sophisticated equipment is quite awe-inspiring. The Dent Blanche is the climax to Dorothea’s Climbing Days as it is here and the sense of satisfaction that Richards felt – to have completed his mission and seen his book take shape – must have been exhilarating. He’d at last got to know his great-great aunt through her diaries, her husband’s letters, the memories of those who knew her and climbed with her, and via the very rocks and slopes that she’d conquered all those years before.

And yet as compelling and convincing as this odyssey is and despite the reprinting of Ivor’s brilliant 1927 essay The Lure Of High Mountaineering, I have to admit that I’m still not sure I fully understand the reasons why some people feel compelled to climb mountains. Having read Dan Richards’ hair-raising exploits in the Cairngorms and Switzerland and been beguiled by the nature of the quest he undertook and the reasons he did it, I can appreciate some of the emotions that must seize and inform the mountaineer’s psyche. Ivor talks of “boredom with comfort” as a prerequisite, the “worship” of mountains – a feeling that implies beauty, fear and awe, and mountaineering as a “concentrated form of exploration”. And then there is the exhilaration involved in high-level risk, the satisfaction of successful technique, and the sense of achievement on a triumphant ascent having been tested in often brutal conditions both mentally and physically. I see all of that, but as Ivor admits, “to describe a passion to those who do not share it is a difficult enough task, let alone explaining it”. Richards eventually settles for “because it’s there”. “Because it’s there will do” says his friend Robert Macfarlane. “The urge to climb is an ineffable, maddeningly strange impulse – or knot of impulses”. Even Dorothea ends the preface to her book with a somewhat exasperated “Why?”

Nevertheless I enjoyed reading Climbing Days immensely. It’s a totally engaging and satisfying book on every level – as biography, memoir, travelogue and erudite meditation on the restlessness and indomitableness of the human spirit.

*