In Pursuit of Spring by Edward Thomas

Introduced by Alexandra Harris

Little Toller Books. Paperback. Out now.

Reviewed by Cally Callomon

Easter 1913: Edward Thomas left his home in London, a town that, even today, has ‘only climate, not weather’, to take to his bicycle and pedal West to meet the forthcoming advance of Spring head on, avoiding Easter Christian ceremonies, burrowing down into the clod and furrow that held a far more ancient rite.

Brakes gently applied; I should declare a two-fold vested interest, both of which may make this review redundant as an objective study: I cycle.

I cycle a great deal, on ancient bikes, over long distances, often on my own – plus – my introduction to Edward Thomas came via his grandson, Edward junior jr. who lived in the Suffolk village next to mine. Until I met him I had Thomas down as a lesser-known soldier poet, one who I by-passed in my O Level youth, favouring, as we boys do, poems of gurgling lungs, missing limbs and the pointless futility of war, even though we often basked in such pointless futility.

Thomas The Rhymers abound in poetry, be they Henri, D.M, Wyatt, R.S or Dylan in nomenclature, different voices-all, no less valid than each other, but enough to confuse a Wiki-free lad of 16.

Thomas (the Edward variant), had eyes, and what’s more, he had eyes that saw. His poetry is both depiction and description, but the addition of his photos in this volume turn the travel into poetopography. Grandson Edward also took masterful poetic loaded photos of his Suffolk life, a talent passed down through the ages.

I love a road, me, I quite like a river too, but see neither as more ‘natural’ than each other. Roads and rivers are created by nature: it is natural for creatures, like the human, to wander and leave traces and tracks. If these became the metaled Edwardian roads Thomas pedaled down then these served the same import as any river our ancestors romantically sailed. His description of the road itself harbours no shame, be they rain-soaked, puddled, dusty or beset with previous tyre tracks, ‘but it would take centuries to wipe away the scars of the footpaths up it’ he says of the famous Box Hill, scars added to by the recent Olympian cyclists some 100 years on.

Fortunately the carefully-worded prose survives intact, at times it climbs steep hills, dense words in need of re-reading, at others it belts along with a tail wind. Poor rendition cannot hamper this, only needless editing could, and here you have all the text intact, for the first time since 1914 (and let’s not mention the war here, it was still far off and fleeting when this book came about, even though it claimed poor Edward Thomas just 3 years later).

On the pace of cycling, Thomas comments: ‘…cycling is inferior to walking in this weather, because in cycling chiefly ample views are to be seen, and the mist conceals them. You travel too quickly to notice many small things; and you see nothing save the troops of elms on the verge of invisibility’ impressively prescient given the impending obliteration of both feeble man and mighty elm, both destructive acts of nature in themselves.

Many we cyclists makes notes on our runs, few write them up, the notes remain as a flattering composition in the head; forgotten on the dismount, obliterated by the thirst for a triumphant beer. Thomas kept his notes for us all, the cycling was secondary to the travelling. The book is not so much a commentary of what-is, but a crackling firework of what may-be.

Much like the Tony Harrison of today, Thomas saw biography and whole lives in anonymous gravestone poetry. Anyone who has enjoyed the recent Alexander Masters book A Life Discarded will understand the jewels found in anonymous lives over the cut, thrust and parody to be found in the dubious loaded accounts of famous folk.

Alexandra Harris, in her excellent introduction, cites Thomas as a “visitor riding through it” which he most definitely was. In our current need to be a knowledgeable on-the-spot reporter and accurate witness to every event today, the role of the Tourist is loaded with disdain, but it is from this very removed perch Thomas sees through the everyday into worlds hidden from we self-appointed experts. This is a much needed stance in the Googledays of instant expertise: we know all, can be a know all, yet signify so very little.

When commenting on an anonymous hunting painting hanging on a hotel wall Thomas says “It had a background of a dim range of hills and a spire. The whole picture was as dim as memory, but more powerful to recall the nameless artist and nameless huntsman then that cross at leatherhead” Dim as memory: this is no forensic travel account, more a series of sauntering impressions down by-ways and meanders, loaded with insight.

Thomas appears to meet another man en-route, a shadow, an ‘other self’ the very same person we all talk to when alone and this welcome device unashamed, shows us his different facets; his moods swing as much as his prose. Whilst so many just write about themselves, Thomas includes themotherselves, and still finds time to belt out a few verses of ‘Oh Santiana’ from the saddle.

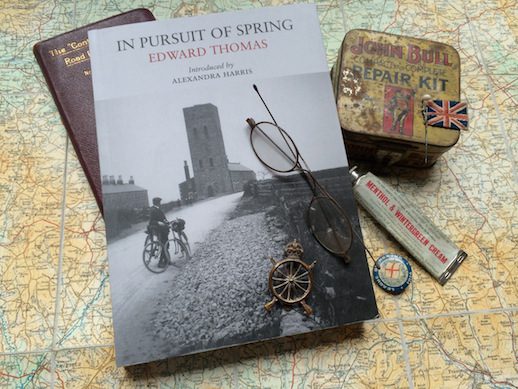

Yet here is where we take a dip. On hearing of this book I eagerly awaited the postman and was bitterly disappointed to find that the large format hard-bound full colour scanned epic was not to be. A standard thin-papered paperback landed on my desk. The photography is weakly rendered, with text show-through to further obfuscate; the best image sits on the front cover in full crisp detail – oh if only!

Cardiff University house a treasure chest of un-published Thomasiana so, perhaps, all is not lost and the success of this book (helped by your purchase dear reader) will result in less cheap versions of his writing, his scores, notebooks, letters, flower pressings and clay pipes (on which there is a lengthy discourse in this very book to whet the tobaccatite) may follow. Little Toller have published triumphant tracts from previously lost Writers Of Place, but here they stray into territory that warranted greater depth and quality and, I fear, their initial attempt has scuppered another version for 10 more years. Until a next time then.

There is only one thing I can do with this book and that is to re-cycle it:- Next Spring I will repeat Thomas’s trip, day-for-day on the same machine as he used (a Sunbeam or Rover by the look of the front cover). I’ll carry period map and tent, I’ll try and take modern versions of the photos on my ‘phone, I will re-read the book, draw a map, carry this book (which is infuriatingly just too large for the jacket pocket!) and scribble notes inside it, let it get wet and weathered, like the very best Wainwright guide, and when this combines with my memories and private thoughts it will truly come alive. Anyone care to join in – or is this for the other-self?

In Pursuit of Spring is on sale in the Caught by the River shop, priced £15.

Cally Callomon on Caught by the River

Alexandra Harris is among our guests at this years Port Eliot festival.