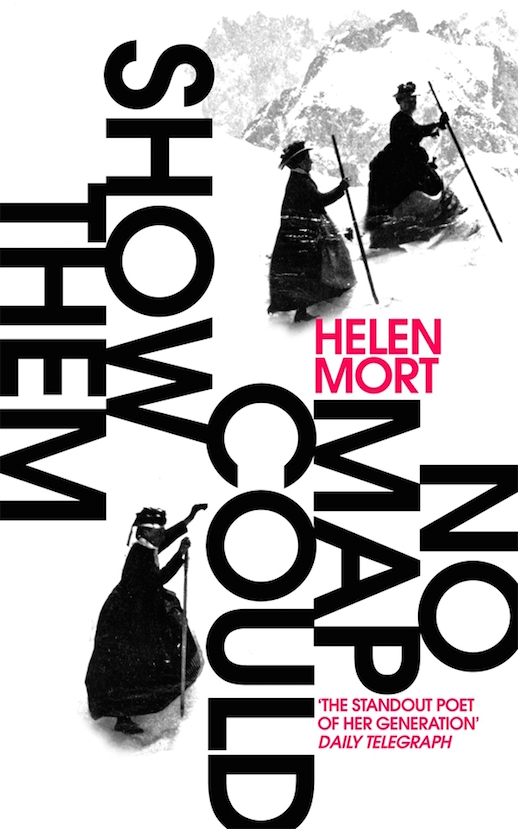

No Map Could Show Them by Helen Mort

No Map Could Show Them by Helen Mort

(Chatto & Windus, paperback, 96 pages. Out now and available here in the Caught by the River shop, priced £9.99).

Review by Will Burns

What a title No Map Could Show Them has become over the past few weeks. A month in which a stitched-together nation state has publicly exploded its identity, while simultaneously seeking to smudge and blur (my attempt to coin a statesperson’s equivalent of ‘shock and awe’) the boundaries and borders of the previous centuries’ maps, has left almost no aspect of British-European life un-examined, un-pawed, un-broken. And so how welcome a book concerning itself with our place in the land, and our place amongst each other.

The word ‘Them’ is key: throughout it feels as if these poems’ pronouns, those words which have become the battleground of recent explorations of gender politics, are vital footholds. The first poem’s ‘yous’, for example, suggest from the outset the tension between the female climbers and mountaineers from history (and almost everybody else) which the collection nominally addresses. It’s a technique that is explored throughout the first half of the book in subtle, clever ways. In ‘Ode to Bob’ there is a heavy, definite ‘he’ in opposition to ‘us’, while poems like ‘Scale’ and ‘My Diet’ locate the speaker’s problematic selfhood in ‘I’ and ‘my’, until the last three lines of ‘My Diet’, where the focus shifts, uncomfortably and suddenly onto ‘you’, the critical, unforgiving gaze of our societal pressures suddenly taking all of us in, reader/voyeur and the speaker of the experience alike.

Throughout Helen Mort’s second collection, there is interesting work being done on notions of identity, and the locus of identity within our physical surroundings. Of course, mountain climbing might be as essential a cypher for this sort of examination as there can be. Again, the first poem is exemplary in that the speaker, the human figure, and the titular mountain itself shape-shift into one another; stomachs are boulders, talk weather, legs stony. But all this, too, weighted with anger. ‘Skin-coloured sandstone’ is ‘wedged where your breasts should be’. One lands on the word should as heavily as the poems ‘rockfall’ words themselves.

By the third poem, ‘How to Dress’, our (or someone’s) clothes are added to the process. There are still malachite ankles and a ‘mouth becoming fissures’, but we also have ‘jackets made of shale’. These are the ‘clothes they want/to keep you in…’ . One is forced to ask – what use indeed will maps be to those who have transformed into the land they wish to chart, or have seen charted by others at their expense? The paths of maps, or physical experience as rendered order, are, in the poem ‘An Easy Day for a Lady’, made by ‘you’, unmade by ‘we’. This suggests the true impermanent nature of geography, as opposed to a false, sentimental permanence of a hitherto patriarchal understanding of things-as-order, the dialectical argument here not necessarily just about gender though, which would be too simplistic for the intelligence behind these poems, but rather that there is a subtler way of interacting with the landscape than merely the making of paths (or, in a more politically charged sense, the following of them). As the speaker says herself in the poem ‘Hill’,

I mean to say there must be better ways of putting things,

unwritten routes, stone-knuckled paths to overshoot, words

practised till they come out rough. And from this height,

and on this tilted Yorkshire earth it seems enough.

And the sensory inversions here – ‘unwritten routes’, a ‘practise’ that ensures ‘roughness’ not only harmonise exquisitely with that ‘tilted Yorkshire earth’, but also with the strangeness of the sense of self and self-identity that permeate the book. It’s examined in a multitude of ways but at its most potent, through disorientating self-identifying images. So we have a bloodhound ‘too old to bleed’, Beryl the Peril whose ‘..plaits are strings/of sausages…’, ‘skin/ like apple skin,’ the seemingly problematic nature of food and self culminates with both technical and emotional precision in the final line of ‘My Diet’, where we are invited to ‘eat yourself, slowly,/ starting from inside.’ An image echoed later in the sequence of poems dedicated to Alison Hargreaves in the ‘bitten fingernails’ of ‘Solo’. And this in turn an image which returns again later in ‘Kalymnos’, where ‘The rock took all my fingerprints from me.’ A line which could serve as a summation of this book at its most interesting, somehow. The confiscation of our one truly individual feature by the implacable natural. The penultimate line ends with the word ‘replace’.

This sense of a barely-there membrane between physical phenomena is perhaps most striking in ‘The Fear’, where a ‘flute pushed into my hand.’ feels almost as if it has come through the flesh and bone, and indeed subsequently leaks ‘through the seams of my clothes,/grew into a stain…’ it is the sheer physicality of the writing, and the clarity of image that sustain this level of thought throughout the book. There is much here besides the idea of gender in the face of nature at its most formidable, although childbirth, prostitution and class struggle might all fall under that banner as well. By the end of the book, on each subsequent reading, what I believed in most, I suppose was the sense of how, for some, the ability to clamber ‘from your own taut skin’ can be the difference between a kind of life and a kind of death.

I must admit to feeling sheepish about reviewing this book – in what way is it justifiable for me to take up any space in the conversation these poems are having? Another male voice pronouncing on a book and artist whose achievements far outstrip his own. However I was very glad to read it, and to re-read it, review it and to say in public what a powerful book it is.

*

Will Burns has co-curated the Caught by the River Thames Faber Poetry Chapel, along with fellow Caught by the River poet-in-residence Martha Sprackland. Helen Mort will read in the chapel on Saturday 6 August. See the full Faber Poetry Chapel lineup here.

Will Burns on Caught by the River/on Twitter

Helen Mort’s website/Helen on Twitter