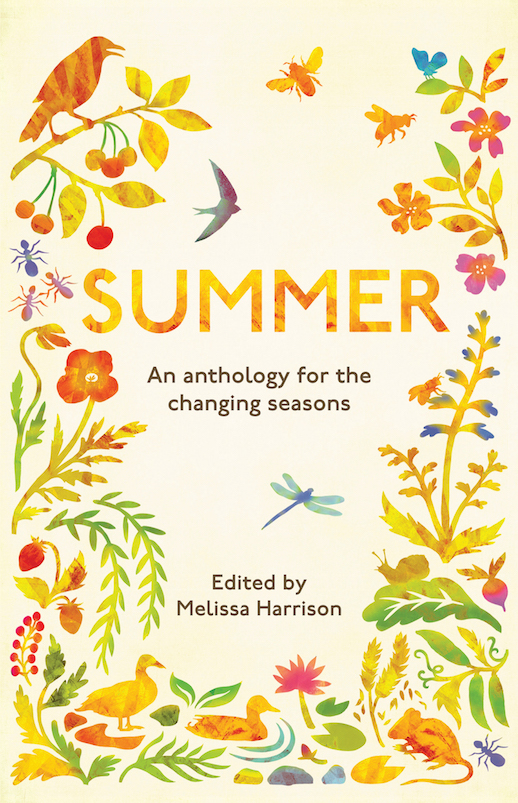

From Summer: An Anthology for the Changing Seasons, edited by Melissa Harrison, published in conjunction with the Wildlife Trusts by Elliott & Thompson. Out now in paperback original (available here) and ebook.

From Summer: An Anthology for the Changing Seasons, edited by Melissa Harrison, published in conjunction with the Wildlife Trusts by Elliott & Thompson. Out now in paperback original (available here) and ebook.

Words: Michael McCarthy

Early July: the woodland was exquisite, glowing with shimmering green light and vividly animated with butterflies, ringlets and large skippers nectaring on the bramble flowers, but I barely noticed it, my heartbeat already accelerating, picking up speed with every step towards…the treasure. It was a hot bright morning and I began to perspire as we slogged up the path through the trees, four of us in single file with me, the initiate, bringing up the rear: the other three had seen the treasure before. Were their senses quivering with anticipation like mine? You know what? I think they probably were.

They turned off the path then, suddenly, at some barely perceptible marker I never saw, and dived into the trackless undergrowth and I followed, stumbling across the slope and clambering over fallen trunks until eventually, deep in the woods, we came to a small fenced enclosure; and there inside it, in the dappled shade of a young beech tree, was the end of the quest: three slender stems each bearing half a dozen purplish-pink blossoms. I gazed on them, spellbound.

Why do orchids excite us so? What is it about them that triggers, in those who begin to feel the passion for them, passion which is so extraordinary, passion which can lead not just to enchantment and delight but to covetousness, cupidity and criminal greed? I have spent a long time thinking about this and I have gradually come to believe it is because orchids are the flagbearers, the standard-bearers for one of the great revolutions in life on earth: the emergence of the flowering plants. What a remarkable revolution it was: 500 million years ago, the first plants that began to cover the land surface, which were pollinated by the wind, bore only one colour, that of their chlorophyll, green; yet about 150 million years ago, some of them began to employ insects instead of the breeze to move their pollen around, and equipped their reproductive organs with brightly- coloured petals to catch the insects’ eyes, and so, in a great outburst of beauty, flowers were born. A flower to us may be loveliness made manifest, but we should not forget that in evo- lutionary terms it is merely a device to attract a pollinator; and since orchids are the largest plant family, with more than 25,000 species in the wild, they have had to compete fiercely amongst themselves to devise ever more eye-catching forms and colours to entice their insect helpers, in the dim light of the rainforest, where most of them evolved.

The result: these are most glamorous, exotic, outlandish, beautiful blooms on earth, in the tropics, especially. I go to look at them in the glasshouses of Kew Gardens, this great cream six-pointed star from Madagascar, this pale purple bell with a yellow-orange heart from the Colombian Andes, this bizarre maroon-spotted cross from Borneo, and I see at once, these are flowers taken to the limit, they are the very epitome of florality, they are flowers set apart: they are the priestly caste of the plant kingdom.

Britain’s orchids, with one great exception, are not riotously exotic in their beauty like their tropical cousins, yet I love them most of all, for their loveliness which is restrained: they are blooms of the temperate world, elegant spikes of tiny flowers in pastel shades, pink, cream, pale violet, pale purple, which sometimes seem to me in their understatement to be very English: plants designed by a civil servant. But they are nonetheless touched with distinction: they too are members of the priestly caste. In the meadow or on the downs or in the woodland, they stand out. We have just over fifty species and every year, like many others, I go looking for them, burnt orchid, spotted orchid, fragrant orchid, marsh orchid, pyramidal orchid, man orchid, lady orchid, bee orchid, and my favourite, greater butterfly orchid, an enchanting slender tower of separate, small creamy blooms you find trembling in the shade. Excitement attaches to encountering every one. In their beauty they are among the great signifiers of summer, like the woodland butterfly trio of white admiral, silver-washed fritillary and purple emperor, or that other trio in the sky, the ‘summer triangle’ of the stars Altair, Deneb and Vega.

Yet it is not just beauty which provides the allure: there is rarity too, the attraction of which seems to be hard-wired in our genes. Orchids are not just the largest plant family on earth, they are the most threatened, as a direct result of unrestrained human desire for them, and many have been driven by collectors to extinction in the wild; in Britain, several of our species, such as the military orchid, are among our least common flowers, and three head the list of our supreme rarities: the ghost orchid, the lady’s slipper and the red helleborine. The first I suppose I may never see, as it is a mysterious small pale flower which only intermittently appears, deep in the leaf litter of the woodlands: it was last seen in 2009, and before that, in 1986. The second is a celebrity: the lady’s slipper is the one British orchid which in its appearance unmistakably belongs with its tropical cousins. The flower’s lip, or central lower petal, is huge, blousy and bright banana-yellow, shaped like a shoe or a slipper or a clog – a piece of footwear, certainly – while behind, the other petals that frame it are drooping pennants of intense maroon. It is gaudy, glitzy and totally over the top, it is unique in the British flora, and not just for its looks, but for its story. For the British population of the lady’s slipper was driven by collectors to extinction’s very edge: it was reduced to one single plant, guarded in total secrecy by a small group of devoted botanists for more than sixty years, until eventually, in the 1990s, scientists at Kew learned the difficult trick of propagating it in the laboratory and it was saved: dozens of seedlings have now been planted out.

More than can be said for Cephalanthera rubra, the red helleborine. This is now critically endangered, it is Britain’s most threatened flower, being reduced to three locations only, and it is also exceptionally lovely: the beauty and the rarity combine in an incomparable allure, which is why my heart beat faster and faster as on that hot day at the start of July I stumbled through the Chiltern beechwoods towards it. And I was not disappointed: I gazed and gazed. I trembled with excitement. I wanted to shout for joy. In the Chilterns, for God’s sake, in the gentlest of landscapes, what can do that to you in the Chilterns?

Only orchids.

*

Summer follows on from Spring: An Anthology for the Seasons, also edited by Melissa Harrison and published by Elliot & Thompson, in conjunction with the Wildlife Trusts, earlier this year. Read an extract here. Available to buy here.

Melissa takes to the Caught by the River Thames Waterfront Stage on Saturday 6 August, where she’ll be considering seasonality.