The Keartons: Inventing Nature Photography by John Bevis

The Keartons: Inventing Nature Photography by John Bevis

(Uniformbooks, paperback with flaps, 192 pages. Out now and available in the Caught by the River shop, priced £14.00.)

Review by Justin Partyka

I spend a lot of time out walking in the country – down tracks, lanes and footpaths, in woods and around fields. I have hardly ever come across a bird’s nest, let alone one with eggs or a bird in it. Perhaps I don’t know where and when to look. But I think that maybe we live in an age when there just aren’t birds’ nests around in this country; not like there used to be. Mark Cocker has recently written of “the great thinning” : the devastation that post-WWII chemical-dependent industrial agriculture has brought to our wildlife and landscape. Roundup being just one of the many poisons which have been sprayed daily over little Britain for many many years.

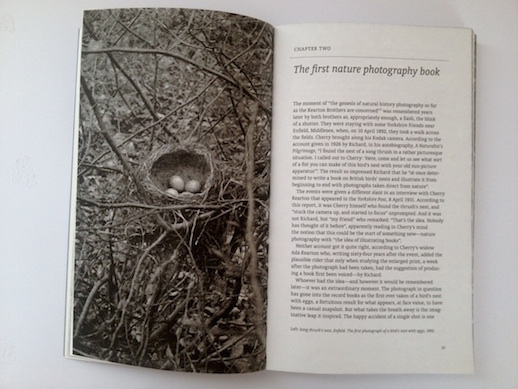

It was clearly a very different time and a very different country when the ingenious brothers Richard and Cherry Kearton began work on their first book of nature photography, British Birds’ Nests: How, Where and When to Find and Identify Them (Cassell, 1895). On 10 April 1892 while visiting friends in Enfield, Middlesex, the brothers took a walk across the local fields. Cherry had his Kodak camera with him. One of the brothers – there is dispute over which – found the nest of a song thrush containing eggs. Cherry made a photograph of it. It is the first ever photograph of a bird’s nest with eggs in it. The result so excited Richard that he decided that they would produce a book cataloguing British birds’ nests and illustrate it throughout with photographs.

Cherry’s first nest photograph is a snapshot rather than a detailed scientific image. It is slightly soft in focus, but that’s good. The cause, most likely, is the camera technology of the day, but it also makes me think that Cherry had an artist’s eye rather than merely a naturalist’s. His composition does too: an array of sparse branches crisscross the frame and in the centre, cradled amongst them and tilted towards the camera, is the thrush’s nest with three eggs clearly visible. In his new book – which is essentially a biography of the Keartons – John Bevis includes the photograph as a full page spread, as he also does with a number of other photographs. This may well mean that the photograph is cropped. It doesn’t really matter, that much. But as a photographer, for me this important photograph has lost some of its historical context due to this choice of reproduction. I want to know what size the original image was, and it would have been even better to see the photograph within the context of the book in which it originally appeared.

This first book was an ambitious project for the Keartons to take on: find a nest for each of the 183 species of British breeding bird and photograph it with eggs and / or a bird in it for identification. Even to attempt it today it would be daunting for most people. Now we can zoom up and down the A roads and motorways to travel the country. The Keartons had only steam train, horse cab and foot at their disposal. Additionally, they could only work during breeding season – mainly April, May, June – therefore every minute they had to work on the project was valuable. Bevis writes that the brothers would get up at 4.30 on weekday mornings so they could go out locally searching for nests before heading to work at Cassell publishers in London. On weekends they would make extensive journeys out to the country’s diverse bird breeding habitats.

Bevis includes a number of photographs depicting the Keartons at work. These are fascinating and really provide insight into the efforts the brothers went to in their work – especially Cherry, the daredevil of the duo. In one photograph he is seen hanging from a rope alongside his camera and tripod. In another he is up to his waist in river water photographing a kingfisher’s nest. Perhaps the craziest of these photographs shows Cherry with the help of an assistant (possibly Richard) photographing a nest in a tree. High up in the crown, Cherry is seen halfway up a ladder with his camera, the ladder precariously balanced on the tree’s branches; there doesn’t even appear to be a safety rope! It’s clear that the Keartons were aware they were ahead of the game in their techniques for establishing the field of nature photography, and they had the foresight to document their methods as they went along. I find these photographs of the Keartons at work even more interesting than the nature photographs themselves.

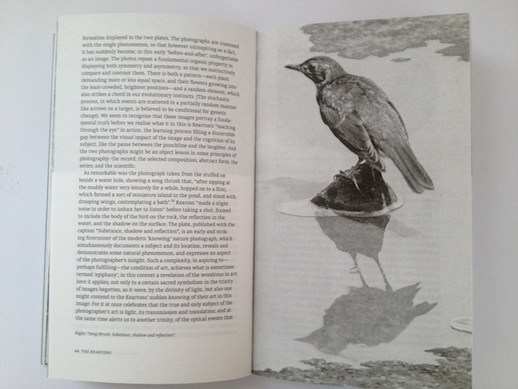

As the Keartons’ work progressed it became obvious that the cumbersome and slow photographic technology of the day was at odds with the fleeting characteristics of the subjects of nature photography, most notably birds. How could the brothers get closer to a subject within its natural habitat? The answer was the hide. In 1898 they experimented with an artificial tree trunk. The book includes two photographs of this: one showing the canvas and bamboo construction open with Cherry inside with his camera, the second image showing the hide closed and concealed with various greenery. While this method was successful for tree and hedge nesting birds, the brothers needed a different approach to photograph the ground-nesting birds on open land. Richard enrolled the help of an old friend named Rowland Ward, a taxidermist in Piccadilly. Kearton sent Ward an ox hide acquired from a butcher and instructed him to mount the animal standing up. Bevis describes in detail how this object was constructed so that it would function as a hide for Cherry to conceal himself and his camera. As mad as it sounds, Bevis recounts that the stuffed ox hide proved successful for the Keartons, who were able to photograph nesting larks from inside it, as well as making what must be one of their best bird portraits: ‘Song thrush. Substance, shadow and reflection‘ – which, as the title describes, features the thrush perched on a small rock in the centre of a water hole, alongside its own shadow and reflection in the muddy water. But like many eccentric Victorian inventions the ox hide also had its problems. On one occasion the heat and smell in the confined space caused Cherry to be overcome with dizziness and the stuffed beast toppled over. Cherry lay trapped for an hour before Richard returned to rescue him.

The Keartons: Inventing Nature Photography is a useful overview of the careers of these brothers and highlights just how much they achieved in the time they were active. Between them they published around forty books, seventeen of them co-publications (between 1895 and 1926) which featured Richard’s text and Cherry’s photographs. The Keartons also became involved with Theodore Roosevelt, himself a nature enthusiast – mainly of the hunting variety. As a naturalist Richard was invited to advise the President and in 1908 he made a trip to Washington to meet with him and birdwatch on the Potomac River. Roosevelt invited Richard to be the “expedition photographer” for a planned safari in Africa the following year, but due to other commitments he declined.

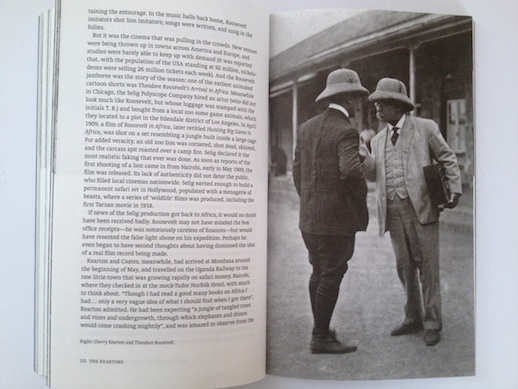

Seeing the opportunity, Cherry – accompanied by his brother-in-law William Coates, a Fellow of the Zoological Society – decided to undertake his own safari (Cherry shooting with a cine camera instead of a gun) with the intention of meeting Roosevelt and his party in the bush. Cherry managed to do just that and Bevis includes a photograph of the two men deep in conversation, both adorned with the requisite safari hat of the colonial time. Cherry persuaded Roosevelt to let him film elements of the president’s exploits in Africa and this became Roosevelt in Africa, a motion picture approximately 25 minutes in length. Cherry had made the trip a success: “He had gone to Africa a British bird photographer and returned an international wildlife film-maker.”

The film proved to be lucrative work for Cherry and he launched a new career in motion picture-making, with return trips to Africa and visits to other destinations. Bevis writes in depth about various scenes in Cherry’s films which have had their authenticity questioned. These include one clip of a lion drinking, in which contemporary award-winning wildlife cameraman Gavin Thurston believes the lion is tamed. In another scene depicting a lion spearing hunt, filmed by Cherry in 1910, an editor of David Attenborough features has suggested that the lion is tethered. Perhaps Cherry overstepped the mark in his quest for fame and fortune. But even early on in their careers, the Keartons would at times adjust birds’ nests, or trim branches to illuminate nests, in order to make better photographs. What these insights into the Keartons’ work reveals is that the decision making involved in documentary work is complex, and the distinction between objectivity and subjectivity is not clear cut. The recent critical discussions around Steve McCurry’s “manipulated” photographs, National Geographic’s moving of the pyramids for their cover, and the BBC’s “fake” polar bear cub footage also indicate that such controversy is still evident today.

The French may have invented photography when Louis Daguerre developed the daguerrotype process in 1839, but for almost the next 100 years the British were making important contributions to the medium’s history: William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature (1844-1846),the first commercially published book to be illustrated with photographs; Julia Margaret Cameron’s soft focus portrait studies made between 1864 and 1875; and P. H. Emerson’s nine years of work in “naturalistic photography” which championed the medium as an art form (1886-1895). John Bevis’s study of the Keartons clearly indicates that they too should be included as major British contributors to this important period in photography’s history. It was only when Henri Cartier-Bresson got hold of his first 35mm Leica camera in 1932 and took to the streets that Britain’s contribution to photography was well and truly left behind.

*

Justin Partyka’s latest work is Not Exactly Nature Writing, a series of photographs from Walnut Tree Farm, home of Roger Deakin. Details can be found on Justin’s website. A book of the photographs is available here.